Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens announced the city is taking steps to bolster a housing program for low-income people living with HIV.

Federal funding for the Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS program, or HOPWA, declined sharply in metro Atlanta in recent years, leaving some providers with deep cuts to their budget. In response, Dickens convened a task force to help the city navigate the changes.

So far the city has committed $250,000 in a trust fund for HOPWA and promised to coordinate with other leaders in the metro area to fill funding gaps in the program.

After years of the city struggling to effectively administer the federal housing program, local advocates are cautiously optimistic. WABE reviews the program’s complicated history and the current concerns.

Why did federal funding for HOPWA in metro Atlanta drop so dramatically?

The federal government used to deliver funding for the program based on the total number of cases of HIV in an area. That included those who had already died from the disease.

But in 2016, Congress changed the way it funded the program. Now the government considers the number of people currently living with HIV in an area when distributing federal assistance.

Even though Atlanta has one of the highest rates of new HIV diagnoses, the Congressional change led to a dramatic drop in this federal housing assistance. In 2021, the city of Atlanta received $22.7 million. In 2022, that figure plummeted over 40% to roughly $13 million.

“If you do not have an adequate place to stay, there’s no way you really can focus on taking care of yourself, living with HIV.” – Daniel Driffin, Atlanta HIV/AIDS activist

How is that affecting housing services for people with this condition?

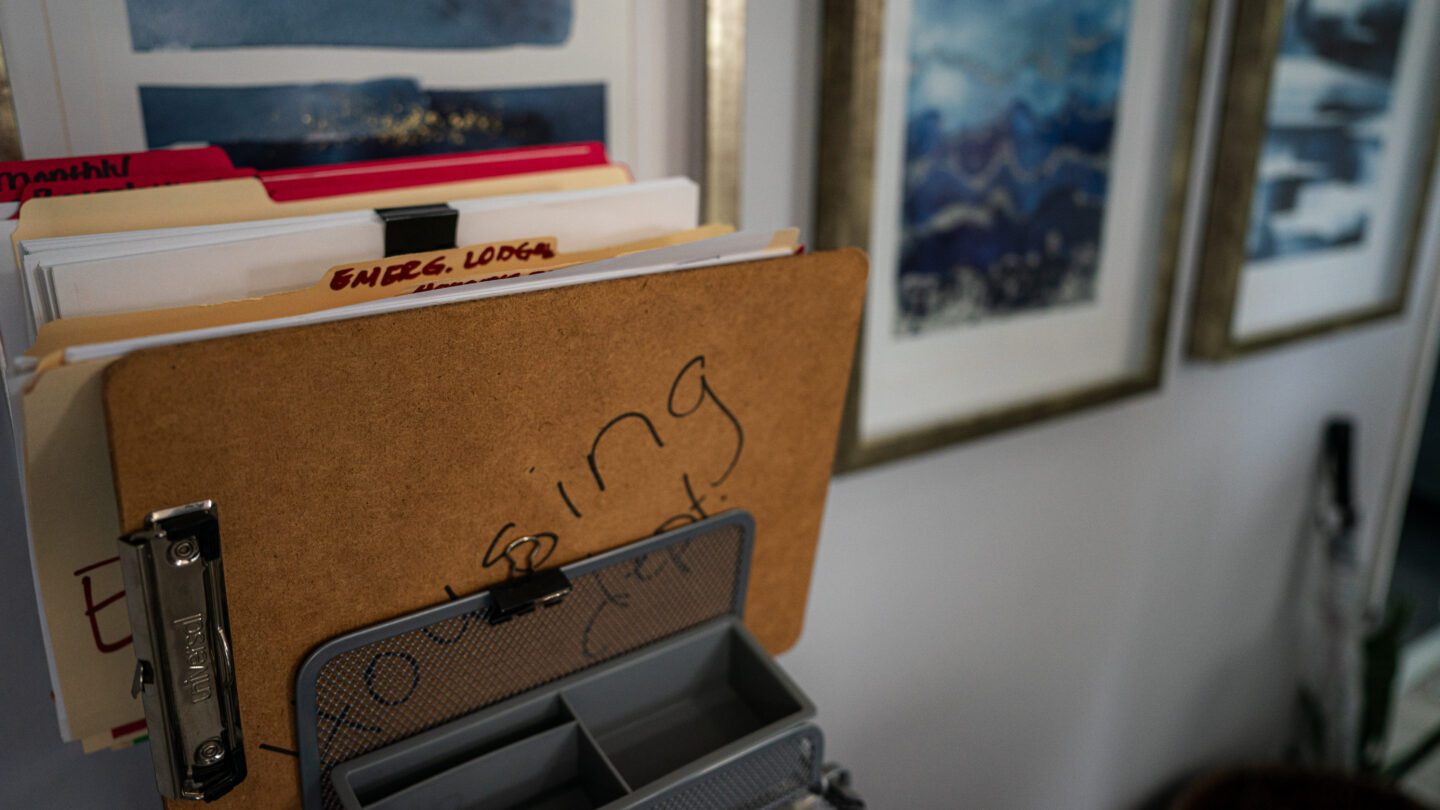

At the Midtown nonprofit NAESM, difficult decisions are common. The group’s finance director Alex Zohore said they receive calls from people who are living with HIV and are on the brink of eviction.

They’re often several months behind in rent. But for short-term assistance, he said his nonprofit — which focuses on Black gay and bisexual men, who have disproportionately higher rates of HIV — has a waitlist of about 50 people. It can’t afford to cover several months for each person. “When we face that situation, it’s like, hey, we can only provide you for a month,” Zohore said. “Where do you get the three remaining months?”

Zohore said NAESM will refer people to other organizations for the remaining assistance but he said they don’t always have success elsewhere. “There’s no capacity. Like, every agency is actually at capacity.”

Atlanta used to have a problem distributing these funds

Under former Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, the city grants department struggled to get money to the providers offering these housing services to people with HIV.

Nonprofits have to first pay for housing services on their own and then get the costs reimbursed from the city. As WABE previously reported in 2021, one nonprofit had to wait months for reimbursements — at one point the city owed it $1.5 million — forcing it to pay clients’ rent late. In 2019, a few hundred tenants at another nonprofit nearly faced eviction. Atlanta was so slow to use the federal funding that it had to return $5 million at one point.

Advocates say the city has resolved those issues and has swiftly moved through available funds — part of why providers have been feeling the effects of the federal cuts.

A team of WABE reporters take a deeper look at the issues affecting LGBTQ people in Georgia. Plus, LGBTQ Atlantans in their own words, Pride events calendar, LGBTQ coverage from other NPR stations across the South and more.

Whose responsibility is it to address the shortage of federal funds?

Since the city manages the HOPWA program locally, advocates said they’re glad to see Atlanta puts up its own money — even if it’s coming years after the announcement of federal cuts. “I think we waited a little too late but we are moving finally,” said Daniel Driffin, a public health researcher and advocate.

Advocates said the initial $250,000 investment in the HOPWA trust fund is not enough. The task force recommendations asked for $1 million. But they also acknowledge this is not solely the city’s problem.

Atlanta receives HOPWA housing assistance for 29 counties, extending as far out as Carroll and Barrow counties. This is why the city is tasked with reaching out to and seeking resources from other metro area leaders.

Housing is key to survival for people living with HIV, according to local and national advocates

This is among the reasons HUD started the HOPWA program in the 1990s. “If you do not have an adequate place to stay, there’s no way you really can focus on taking care of yourself, living with HIV,” Driffin said.

Without a home, people are less likely to take their medications and prevent the fatal consequences of the disease.

The stakes are especially high in Georgia.

The state not only has the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses, according to local and federal data compiled by researchers at Emory University; it also has one of the highest rates of death for people who contract the virus.

This story is part of the ongoing series Beyond Pride, in which WABE reporters take a deeper look at the issues affecting LGBTQ people in Georgia. Plus, hear LGBTQ Atlantans in their own words, check out a Pride events calendar running through the fall, LGBTQ coverage from other NPR stations across the South and more.