Listen to WABE’s investigation following Forest Cove residents over the last year as a serial podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music and more.

Winter-Spring 2021

“Once they move you, you got to go back.” On an overcast morning last March, Ms. Peaches is out in the yard. She’s explaining to a neighbor a letter that just went out to all the Forest Cove households. The notice, written in formal language to meet federal requirements, notifies residents they may be relocated in a few months. The relocation is supposed to be temporary, while the complex’s incoming owner carries out renovations. If tenants don’t return afterward, Ms. Peaches tells the woman they’ll lose their rental assistance from the federal government. She says they have to come back.

This is typical for Ms. Peaches — a name she’s always used, although when she was a kid it was just “Peaches.” She’s a petite woman with nose and lip piercings and short bleached-blonde hair. She’s wearing, on this day, a gray and pink tracksuit. She’s lived at the Forest Cove apartments for about 20 years, always on the southside. The two sides, north and south, cover about a half mile along McDonough Boulevard in the southeast Atlanta neighborhood called Thomasville Heights. With 400 units, the complex is one of the largest federally-subsidized complexes in the city. And many of the residents come to Ms. Peaches for updates.

Ms. Peaches is also the one who often speaks up. By this time last spring, she’s been in news stories for years. At a rally outside the complex in 2018, she told WSB-TV she was protesting, “‘cause our living conditions, it’s horrible. It’s disgusting.” “We got grass growing high,” she said a couple of years later to Fox 5 Atlanta in a piece about the complex’s overflowing trash. “We got infestation, mold.” The reports are rare examples of people calling her by her birth name, Felicia Morris. But other than that, her news appearances aren’t special moments for Ms. Peaches. For years, everything at Forest Cove has stayed the same — if not gotten worse.

In that time, residents have waited on a promise: a new owner who will take over and fix a complex with some of the most severe conditions in the city and one of the highest rates of violent crime. The sale is not complete yet but the relocation letters are part of the company’s plan for renovation. In the coming year, Ms. Peaches will fight through continuous delays to hold the company to that promise, and she will keep fighting until it finally falls apart. It’s not clear on this day, but in February 2022, the future of the entire complex will be in doubt. Ms. Peaches’ final year at Forest Cove will be a story of the effort and pain of federally-subsidized tenants who try to maintain decent, safe and sanitary homes, as government agencies often stand by.

But on this first morning last March, Ms. Peaches simply walks me through the current state of the complex. The buildings at Forest Cove are like two-story blocks, stacked next to each other, with brick outside the first floor and tan siding up top, although mildew’s made the color pretty dull. Each block has a few narrow townhome-style units. We sit behind her unit in the patio area, which she keeps tidy. There are several healthy-looking potted plants and her small poodle looks out through the doorway. It seems like any other home, which is not how Ms. Peaches describes the rest of Forest Cove. “Look, if you could just look,” she says, speaking like she’s outlining a basic fact. “It’s sad that you have to be a human and stay in a place like we’re not human.”

This doesn’t feel like an exaggeration. Forest Cove is like few other low-income apartments in Atlanta. Despite its 400 units, only about 200 families actually live here. So almost half the units are vacant. The view from her patio is mainly abandoned apartments. Many are boarded up with unit numbers spray-painted on the plywood. Others are wide open. Some even caught fire. “Got a burnt unit over there, been over there for about three years,” Ms. Peaches says, pointing to the apartment across from us. The second floor is only a gaping hole, some charred framing left. The gutters are twisted and hanging off.

She says abandoned units like that are often full of trash. “The neighbors or somebody get trash bags and throw them in there. And it looks so bad,” she says. “But see, the only reason why that one ain’t full yet is because I stay right here and I’m not gonna let you throw no trash over in that apartment.” Trash is often scattered throughout the complex too, in the parking lot and the yard, despite signs around the complex saying stuff like, “community pride: please don’t litter.” The ground is only clean today because of Ms. Peaches. She has a bag of trash she picked up on her patio. She says last night she told management and other tenants she’s not cleaning up anymore. “I’m not,” she says.

And all of this is outside the units people live in. The problems inside can be serious. Ms. Peaches hesitates to take me into the interior of her apartment because of issues with her floor. A hole in her kitchen goes all the way through. “I have to keep it covered up,” Ms. Peaches says. “Then when I cover it up, the other day, I seen a rat run through. I be like, ‘Where he come from?’” Rats and rotten floors are common complaints at Forest Cove. So are collapsing ceilings, broken fridges, broken stoves, broken toilets, broken bath tubs, broken heaters, broken air conditioning, broken doors, broken windows, sewage backing up, water leaking and mold. (All of these are documented in code enforcement complaints.) Ms. Peaches’ unit is one of the better ones.

As she talks through the issues that surround her, she stays mostly indignant. Sometimes she makes jokes. But when she gets to the question of how it makes her feel for this place to be her home, Ms. Peaches’ demeanor changes. She pauses, holding back tears. “I feel hurt. Wouldn’t you? If you had to live around something like this?” she asks. “It’s hurtful. I don’t know how they can keep doing us like that.” Ms. Peaches doesn’t share a lot about herself, only fragments here and there. She grew up in Atlanta, around Vine City. She stayed at the now-demolished public housing project, Englewood Manor. Then Ms. Peaches came to Forest Cove. She finished raising two of her four children here. They’re grown and gone. Ms. Peaches says they ask why she doesn’t move too. She responds that she can’t abandon the other residents. “I told my children, ‘No.’ I’m gonna stay. I’m not gonna leave them like this. They need somebody to fight for them, open their mouth for them, because they scared. First thing they say, ‘they gonna put me out,’” she says. “So I ain’t through.”

As bad as Forest Cove is, many residents don’t feel like they can leave. Almost all the leaseholders are women, often with children and sometimes also working. Or they’re like Ms. Peaches. She receives disability. Overall, the latest census data shows the median income is barely $1,000 a month. That may work at Forest Cove because the rent is based on income — 30% of what tenants earn. But if they ever move, they lose that. They’ll have to pay market rent, in a market where the average two-bedroom costs close to $2,000, according to Zillow. So the residents wait.

Out in the yard, Ms. Peaches calls to another neighbor Lolita Evans, who’s stayed here with her kids for seven years. Despite paying $300 in rent, Evans still has to fix things herself. She says she doesn’t think the property staff cares. “I feel like they gave up on us. They just really here collecting money from the people who have to pay them. Then shoo us, whenever they want to shoo us, to keep us quiet out of their face,” Evans says. She says the property didn’t even let people know the relocation letters were available. Ms. Peaches had to tell residents to pick the notices up. “They done lie so much,” Ms. Peaches says. “Residents don’t even trust.” Evans agrees. “We don’t even know if it’s gonna be true.”

—

Things haven’t gone according to plan before. Forest Cove has been around since the 1970s, always serving mostly Black residents. The complex has had different names: Villa Monte, even Four Seasons. It was built shortly after public housing across the street, Thomasville Heights, which the city eventually demolished too (a decade ago, it tore down most publicly-owned projects). But for most of Forest Cove’s history, it operated differently. It’s part of a federal program known as Project-Based Section 8. That means while the federal government provides the subsidy that covers whatever rent tenants can’t pay, a private owner runs the complex.

There have been several owners at the complex over the years. But to understand how Forest Cove got to this extreme state of neglect, tenants say to just start with the most recent, a religious nonprofit called Global Ministries Foundation. The CEO, a pastor named Richard Hamlet, is a radio personality in Memphis. He’s led mission trips, which he calls “crusades,” across the world. Eventually, Hamlet also got into government-subsidized housing. Under his watch, Global Ministries Foundation bought a few dozen low-income apartment complexes, many in the Southeast, including in 2014, Forest Cove.

In an interview with a Christian talk show a couple of years later, Hamlet said his mission was to help residents in these properties. “Hey a lot of these folks are heroes in my view,“ he said. “The ones that were disadvantaged, underprivileged came into this culture, and now with education and health and wellness, and yes, understanding the love of God and Jesus Christ, we are seeing transformation in these communities.” As the organization sought tax breaks for this work in the form of housing bonds, Hamlet’s organization also promised transformation for the apartments with renovations. But by the time of this interview, local news reports were revealing serious concerns from tenants in many of the Ministries’ properties.

There was a flurry of coverage across the country in 2015 and 2016. In Memphis, local stations reported bed bug infestations and sewage leaking through the walls at the nonprofit’s complexes Goodwill Village and Serenity Towers. In Jacksonville, reporters talked to tenants at places, like Eureka Gardens, who complained of mold. “We’ve followed the millions in taxpayer dollars going to the property owner, a reverend,” the Jacksonville station announced, “and pennies going to residents’ repairs.” There were stories about Forest Cove in Atlanta too. “Take a look at this,” a WSB-TV reporter said, pointing to a pool of water outside a building at the complex. “Smelly stagnant water filled with dirty children’s toys, just feet away from where children play.”

Following these reports, the Department of Housing and Urban Development started to pull funding. It ended rent payments for two of the nonprofit’s complexes in Memphis, the same year as that interview with the CEO. Not long after, Global Ministries Foundation acknowledged the news reports and announced in a letter to bondholders it was giving up on its troubled properties. Eventually, it came up with a deal with HUD to sell nearly 40 of its complexes to a new owner, which could give the most distressed places, like Forest Cove, the renovations they needed. In late 2016 a new owner was lined up. It was set to be a for-profit company called Millennia. And from that moment on, Forest Cove tenants heard a promise: things will get better as soon as Millennia takes over.

I also heard this promise when I was reporting on Forest Cove’s poor living conditions in 2017. At the time, I spoke to a representative for Global Ministries Foundation, Anthony Holm, who defended the religious nonprofit and claimed it invested $3 million on repairs at Forest Cove (bond documents only show $2 million over the four years the company had been owner.) Holm said the new owner, Millennia, would continue to improve the apartments as soon as the sale was complete that year. “Anywhere from five to seven months from now,” Holm said, “there should be a new ownership team who are committed to continuing the full rehabilitation on the property and doing so, we believe, in an expedited fashion.” But the sale to Millennia didn’t happen that year, or the year after, or the next.

–

It’s been four years by the time Ms. Peaches stands in Forest Cove’s courtyard explaining the relocation letters to her neighbors. As the property sits in limbo, it’s not hard to see why tenants feel like they’re on their own. Forest Cove is isolated. It’s located between the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary and long stretches of forest. The only way to get in is by using an access road. Property staff are barely visible, especially on the south side. Tenants say there’s sometimes only one maintenance person for the whole property—management later says there are two. And while plenty of people hang out in the yard and parking lot, I’ve never spotted any security out among the buildings.

Still, Ms. Peaches manages to maintain order. On a sunny morning in April, I meet her again on her back patio while she waits for updates on the sale. She doesn’t seem too interested in talking. Millennia now holds regular conference calls with nonprofits in the area and residents like her but there hasn’t been one recently and Ms. Peaches hasn’t heard anything new. She starts walking me to my car. Along the way, we pass more bags of trash she picked up even though she said she wouldn’t do that again. “I put that over there. I cleaned up last night,” Ms. Peaches says. Then, when she gets to the parking lot, she comes to life. “Girl!” She spots another resident who just took her garbage to the dumpster at the other end of the parking lot. Instead of putting the bag inside, the woman sets it on the ground. Ms. Peaches is furious.

“It’s sad that you have to be a human and stay in a place like we’re not human.”

Ms. Peaches

She screams “Put that trash in the trash can. You right there. Gollee. Hey! Girl put that — uh uh. Girl put the stuff in the trash can. You right there!” The woman walks away, gesturing to her arm like it’s hurt and that’s why she can’t lift the bag into the dumpster. Ms. Peaches doesn’t back down. She yells at the woman for a full minute. She’s still calling the lady “nasty” after she’s out of sight. “I didn’t know you were that nasty,” she says. At this point, it seems like the interaction might be over. But a couple of minutes later, the woman comes back. This time in a car with a man. He then gets out, picks up the original trash bag and throws it in the dumpster. When he’s done, I ask Ms. Peaches, does she run this place? “Just about,” she says, laughing now, “I tell everybody what to do.”

Sometimes that does mean policing the other residents to keep the property in shape. But she can also be their only advocate. An afternoon later in April, I find Ms. Peaches at the complex and this time she’s in action. She tells me to walk. A woman just moved in nearby. Her downstairs window is boarded up from when the unit was vacant. Ms. Peaches is worried. “That’s a fire hazard,” she says. “If that building catches on fire, how them children gonna get out.” She approaches the resident on her apartment steps. “You ain’t gonna take those boards off that window?” Ms. Peaches asks her. The resident says the maintenance people won’t. According to her, they say they don’t have the right drill. “Cause that’s a fire hazard,” Ms. Peaches says. The woman agrees. She seems pretty resigned about it.

Ms. Peaches is not. As she continues walking, she calls the one consistent maintenance man, Mr. Eugene. “Mr. Eugene, you working today? Look you know the girl who stay on my side,” she says as she has him on speakerphone. “She got these boards on the window.” Ms. Peaches tells him what the resident said, how a maintenance worker wouldn’t take the boards down. Mr. Eugene says he doesn’t know who that could have been but it wasn’t him. The sound of his voice is striking, like he’s upset Ms. Peaches would think that. She quickly calms him down. “Mr. Eugene, I know you,” she says. “I know you ain’t saying that.” The call ends with him promising to take the boards off.

Ms. Peaches clearly has sway at the complex and a sense of purpose. She often calls people here “my residents,” like she’s Forest Cove’s caretaker. She puts it this way, “I’m the security guard, I’m the maintenance, I’m the groundskeeper, I’m the mama, I’m the grandmamma and everything else.” But while she has tools like a trash picker and cell phone, she knows addressing the level of issues at Forest Cove is going to take more. I ask her if she ever gets tired. She says “Yeah, I’m tired. But God keep telling me don’t give up. So I hang on in here.” There is also news on this day. Ms. Peaches joined another conference call with Millennia. “They say they supposed to be closing the property tomorrow at 5,” she says. “So they say stuff fittin’ to start happening.” This is the moment residents have been waiting on. When I ask her how she feels about the sale finally taking place, Ms. Peaches still has a little defiance in her voice. “I’m happy. Maybe they’ll get some stuff done,” she says. “Cause I don’t care. I’m gonna stay on them.”

–

She’s gonna stay on Millennia. Ms. Peaches already knows Millennia, and not just from conference calls. Millennia has been on the ground at Forest Cove as property manager. The company took over management of Forest Cove in 2017 shortly after it committed to buying the property from Global Ministries Foundation. This means the company has been managing day-to-day operations at Forest Cove for several years while residents have been complaining. For tenants like Ms. Peaches, it wasn’t the best introduction.

But the Cleveland-based company says the sale marks a turning point for Forest Cove. In early May, Millennia’s public policy director Arthur Krauer and communications director Valerie Jerome join me on a video call. They speak with optimism and a bit like developers. “I think the most hopeful news we can share with residents is that the process is moving forward despite the pandemic and very macro-level factors that affect closings of this size,” Jerome says. Among those macro-level factors, Millennia counts rising construction costs. They also say Forest Cove has been a uniquely difficult property–even in the portfolio of difficult properties from Global Ministries Foundation. Krauer shares the typical price per unit for this kind of project. “In today’s market $75,000 would be a thorough rehabilitation at the top of the market” he says. “For those numbers, Forest Cove is $130,000 a unit. That’s the level of need for this property.” Krauer says Millennia can’t really maintain the property in this state. Forest Cove needs a complete renovation. He says now that Millennia is the owner, it can provide that for tenants. “The simple answer is they’re getting all new kitchens, all new bathrooms, all new mechanicals.” He says there will also be a new community space and easier access to trash bins and dumpsters. “It’s a total rehab from top to bottom.”

Millennia says it’s been communicating with residents every step of the way. I bring up the fact that tenants already have been through years of delays. They’ve also seen Millennia at the property as manager while Forest Cove has deteriorated. But Krauer and Jerome insist the residents don’t need to be skeptical. Millennia is one of the largest private owners of federally-funded housing, with about 200 subsidized complexes around the country. The company considers rehabilitating properties like Forest Cove its specialty. Jerome says residents can even look at other complexes that once belonged to Global Ministries Foundation. Millennia has already renovated several. She shares pictures, showing new floors, new appliances and new exteriors for the buildings. “It is sometimes a long journey to get to the rehabilitation process and stabilize the property,” she says. “But Millennia has done so in other cities and other apartment developments and is committed to doing so here.” The last step before the renovation is to relocate all residents from the property so that construction can begin. Krauer says that’s starting now. “Once we finalize these contracts with our third-party relocation providers, we will begin the process and we’ll move residents out as fast as we can.”

–

With the sale, Ms. Peaches acts a little excited about the possibility of relocating. She jokes about moving into a decent one-bedroom somewhere. But Millennia’s promises still aren’t enough to make her fully believe. I understand better why one afternoon shortly after in early May. The tenant advocacy group, Housing Justice League, calls her and several residents to the park next door to Forest Cove. The group is one of several nonprofits, including the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation and Purpose Built Schools which manages the nearby Thomasville Heights Elementary, that have been active at Forest Cove. Housing Justice League has helped develop a small tenants union at the complex. Technically, Ms. Peaches is president. Before the renovation, it wanted to record a video of the tenants’ experiences. Ms. Peaches sits before the camera first. She’s wearing fake eyelashes and a pink sequin face mask. The cameraman has her count to ten. “One, two, three, four, five.” Then, Housing Justice League’s executive director Alison Johnson starts the interview.

“Okay, tell us your name,” Johnson says. “I’m Felicia Morris.” Ms. Peaches uses her formal name. She sits up straight as she talks. She’s composed. Johnson asks her what Forest Cove was like when she first moved in. Ms. Peaches says it was nice. She calls it “loving.” Then Forest Cove changed, she says. Now they have roaches and rats and their walls are caving in. She says it’s become “a living hell.” Ms. Peaches says she’s been complaining about the issues and still no one has addressed them. She says she’ll keep trying. She sounds resolved. Johnson asks what it’s like for her when she complains and no one hears her complaint. After the question, Ms. Peaches starts to look a little uncomfortable. “It’s a hurtin’ feeling,” she says. “It’s sad. I done cry. I done plead. I done did everything and I still haven’t gotten anywhere. So I don’t know.” Johnson keeps going. “What does that do to you mentally?” she asks. This is when Ms. Peaches voice cracks. She responds “Ms. Alison, you already know what it do. It make me cry.” Tears start rolling down her face. “It makes me cry, Ms. Alison. You know what it do!” Her voice gets louder. Johnson tries to follow up. She asks how this affects her health. But Ms. Peaches has a pleading look on her face. “Ms. Alison, you know it hurt me. I’m sorry, I don’t wanna talk no more right now. Will you let somebody else speak please?”

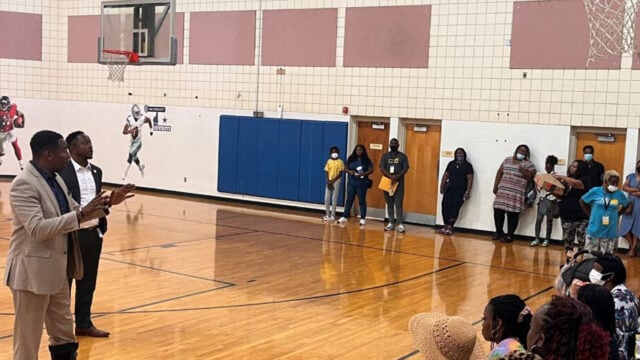

“When is this going to stop?” Ms. Peaches asks last spring. “When is someone going to step in and do something?” Months later, still nothing will change. (Alphonso Whitfield/WABE)

Johnson lets her take a break. After a few minutes, Ms. Peaches comes back and sits down. The eyelashes she was wearing are gone. When she speaks, she still has a little pain in her voice. She says what hurts about living at Forest Cove is this: she reaches out for help and it doesn’t seem like anyone wants to help her. “It tears me apart,” she says. “I don’t like to talk about it because it hurts so bad. It make me cry every time I talk, with whoever I talk to, how I get on the news or whatever I do. It hurts.” Not the buildings falling apart, the holes in the floors or the ground covered in trash but the feeling that no one cares–this is the only thing I’ve seen make Ms. Peaches cry up to now. It’s the feeling that residents have been abandoned like so much of the complex. As Johnson continues the interview, she reminds Ms. Peaches that, according to Millennia’s plan, residents like her get to leave Forest Cove, at least until the renovation is over. Does Ms. Peaches want to come back? Ms. Peaches responds yes. “Because I’ve been through a living hell now,” she says. “So when they remodel I want to come back to something new. You feel me, it’s as simple as that. I feel like they owe it to me. They owe it to me.”

Spring-Summer 2021

The day when she can come back to something new continues to feel far away. After the sale, tenants wait again–this time, for relocation. The company is supposed to hold meetings about the process at Thomasville Heights Elementary. But before they take place, I check in with Ms. Peaches in late May and learn there’s been a fire. She says she heard kids threw firecrackers into an abandoned unit. She shows me what’s left of the unit. The front is all black from the fire. Windows and doors are gone. Burnt trash is pouring out, including drawers, clothing, an entire refrigerator, a boxing glove and a couch. Ms. Peaches says as the fire happened, residents were out watching. The flames from the building caught the tree behind it. When I ask her if anyone lives in the building, she says, yes, one person. She points to the unit next to all the burnt debris. “The lady stay right there.”

Gino Turner, a community advocate, who works at the elementary school, is also here staring at the burnt pile. He says, unsurprised, the fire is maybe the biggest this year, so far in 2021. Turner grew up nearby. He’s been around as residents prepare for this transition with Millennia. To him, the sale wasn’t some magic moment. “Now that they own the property, they’re still doing the same thing that they did when they were the managers,” he says. “The only change? It has changed from one owner to the next.” I ask if his opinion of Millennia shifted at all now that the company bought the property. Turner answers flatly. “My opinion is they went from one owner to the next. That’s my opinion.” Ms. Peaches just looks around and shakes her head. “It’s so many people complaining. When is this going to stop?” she asks. “When is someone going to step in and do something?”

“Given how long this has been happening and how awful the conditions are, did the city literally do every single thing it could as quickly and as forcefully as possible? Probably not.”

Atlanta City Council member Matt Westmoreland

Afterward, Millennia lets me know someone is going to come clean up the burnt trash. Then, the time goes by. The company finally holds the relocation meetings at the school in mid-June. I attend one. Millennia says it will start with the northside of Forest Cove. It plans to move those tenants out starting in July, so it can start construction at the property in the fall. Then, the company will get to the southside, where Ms. Peaches lives. But by the end of July, no one has moved. The meetings just continue. Ms. Peaches gets so frustrated. She says she goes to one of the meetings at the school and yells at the Millennia representatives. Still, the tenants keep waiting.

Then, in late August, something happens that shakes Ms. Peaches. A resident on the southside is shot and killed inside her unit. Ms. Peaches witnessed the shooting. One afternoon a few days later, I ask if she can share what she remembers. Another tenant is there to encourage, reminding Ms. Peaches she’s strong before she begins. She relays what happened in short sentences. “I was sitting on my porch. I seen this car come down the street real fast. So I turned around. I looked at the car. It was a lady who got out a car.” With no security or gates, the woman came right in. She approached an apartment with several people inside, including her daughter’s boyfriend. The police called it a domestic dispute. There was an argument, at least. Then, “she stood right in that walkway and she just started shooting,” Ms. Peaches says.

Police charged the woman with killing a resident named Chiemere Poole. After her death, the usual people aren’t hanging out in the yard at Forest Cove. It’s quiet. Poole was a 33-year-old, single mother with five kids. There are teddy bears and balloons on the porch to her unit, right across the courtyard from Ms. Peaches’. What gets to Ms. Peaches is Poole was trying to get out of Forest Cove. “She had been waiting on Millennium to move us,” Ms. Peaches says. “Every time she come out to ask me, ‘What are they gonna do? ‘When they gonna move us?’ I had to tell her what Millennium told me, a bunch of lies. So, that was the last of it.” She says this should be enough for Millennia to act now.

The next day, there’s a memorial. It’s a hot Saturday night. About 200 people stand in the street next to Forest Cove, all holding red and white balloons. Together, they send the balloons into the sky and say “Long live, Chiemere.” Poole’s mother, Keisha Jordan, dressed in red, then holds a brief news conference with me and one other reporter who came. She says Poole always took care of other people’s children. Now, Poole’s kids will live with her, their grandmother. As it gets dark, residents hang out around Ms. Peaches porch. They think about what security measures could have prevented this shooting. Ms. Peaches just looks out into the yard. A kid says to her “nobody should have never been shooting in the first place,” and she says “tell the news lady that.” Sitting with us, Turner, the community advocate, brings the conversation back to the living conditions. He says they can seem separate from the violence. But the issues are connected. “I think everybody needs to be held accountable, from the city to the owner to the previous owners, all of them, because these lives are precious,” Turner says. With the residents left in this environment, he says it seems like their lives don’t have value.

As the parking lot empties out and visitors from the memorial drive off, it feels as though this moment could spark the action Turner and Ms. Peaches are calling for. But it doesn’t. In another couple days, Ms. Peaches is back to her usual rounds. I follow her as she checks on a woman with several kids, including a baby, living next to a standing water full of trash. “That baby could get sick at anytime,” Ms. Peaches says. She points out a unit with an elderly resident that looks like it might collapse. “That woman is going to fall.” And she interrogates some kids playing outside, in the middle of the day, instead of going to school. “Hey, what’s school today? Don’t y’all go to school?” she yells at them. “Don’t y’all miss it in the morning.” There’s no update about the relocation from Millennia. In a statement, the company says it’s saddened by the resident’s death. It mentions the shooting was a domestic dispute.

–

So, where is the government through all of this? Well before the fire and the shooting took place, the city of Atlanta was aware of the tenants’ conditions. Forest Cove received more than 500 housing code complaints and violations over the last five years according to city records. That’s more than any other complex in Atlanta. It also had the highest count of violent crimes each year for four years ending in 2018 according to an internal Atlanta Police document. Based on emails obtained through an open records request, the code enforcement department, which is within the Atlanta Police, sometimes sent monthly, special details to Forest Cove. Teams of officers documented the broken windows, damaged siding and trash. And this is as plenty of residents called in their own complaints. In one email from 2019, a code enforcement officer said she handled concerns about Forest Cove almost every day. She said one tenant found a rat in her newborn baby’s crib.

But in these years leading up to the sale, the city doesn’t take any major steps against Global Ministries Foundation or Millennia. Both code enforcement and city prosecutors decline several requests to speak to why. Only At-Large City Council member Matt Westmoreland gives an explanation. He says he knew families at Forest Cove when he was on the school board years ago. The complex isn’t fit for anyone to live in. But he says the city is in a tough position. “There’s this really unfortunate tension between seeing the violations and the unacceptable conditions that folks live in with the truth that if you shut it all down, immediately, you are displacing hundreds of people.” He says that’s the only powerful tool the city has: to condemn the place. And that wouldn’t fix the low-income apartments. It would just take them away. “And so it’s a really, really, really, really rough situation. I’ll profess to be extraordinarily frustrated at all parties involved, at how long this has taken because it’s been extremely detrimental to the folks who call it home.”

“I think something that should be highlighted,” she says, “is the millions and millions spent by the federal government for substandard housing, when the government has the ability to both change that as well as to let the tenants leave, and live in better conditions.”

Attorney Laura Beshara

Westmoreland expected the renovation to be done a while ago. In the emails, it’s clear other officials expected that too. Several times over the last few years, code enforcement and the former mayor’s staff decided to hold off on citing Millennia. At one point, in March 2020, city prosecutors even filed a condemnation lawsuit before then letting it go at the end of the year. They believed, based on Millennia’s word, that the sale and renovation were about to take place. In Sept. 2018, a code enforcement officer wrote her boss that Millennia expected the sale to be complete in a few months. In April 2019, an attorney with the city solicitor said Millennia would take ownership later that summer. And in November 2020, Millennia’s CEO Frank Sinito himself sent a letter to then-Mayor Bottoms letting her know that the company would begin relocating tenants from Forest Cove in two months–still five months before it ultimately bought the property. As the sale kept getting pushed back, and along with it the renovation, residents have been stuck. “I think in hindsight,” Westmoreland says, “given how long this has been happening and how awful the conditions are, did the city literally do every single thing it could as quickly and as forcefully as possible? Probably not.”

But as the renovation delays lasted years, there’s another government agency that sat by: the Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD is the one paying the rent. It certainly has known about the conditions at Forest Cove. It has a contract with the owner. As part of that contract, the agency is supposed to inspect the complex to make sure it’s decent, safe and sanitary. HUD hasn’t done an inspection there since 2018. But when it did, the apartments failed. Out of 100 points, Forest Cove scored only 32. Records, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request, show HUD then notified the owner, which was Global Ministries Foundation, that it was in violation of its contract. And after that, HUD left tenants where they were. Despite multiple requests for an interview, the agency never agrees to talk. HUD also doesn’t answer a list of written questions.

Bridgett Simmons, an attorney with the National Housing Law Project, who focuses much of her work on federally-subsidized properties in the Project-Based Section 8 program, says the agency would probably say it has been working to bring Forest Cove into compliance. For HUD, that typically means collaborating with the property owner to improve conditions. If HUD cancels its contract with the property owner, Simmons says that has consequences. “That may mean that the community itself is losing the only deeply affordable housing property in its area,” she says. That’s the reality of the Project-Based Section 8 program, a program leftover from the 1970s. HUD only renews the rental assistance contracts it has. It doesn’t create new ones. She says that makes preserving properties, like Forest Cove, important.

If this is HUD’s approach, though, it sounds similar to the city’s: as though there’s nothing either government could have done all these years to improve the affordable housing at the complex without getting rid of it all together. Dallas-based civil rights attorney Laura Beshara said this leaves tenants with very little power; they’re forced to wait. Beshara, who, along with her law partner Mike Daniel, has spent years challenging conditions in properties like Forest Cove in Texas, says it doesn’t have to be this way. She pins delays tenants have endured squarely on HUD. Beshara says HUD has options it doesn’t use. Several years ago Congress approved an amendment to the law renewing HUD’s funding: now, when a property is unsafe, HUD can let tenants move out and take their rental assistance to a new place, similar to Section 8 vouchers.

She says HUD can do this without canceling the contract. “At that point, they could say, ‘Okay, owner, fix the place up,’ then more tenants can move in and everything will be okay,” Beshara says. “Instead, they’re requiring the tenants to continue to live there.” She and Daniel are suing HUD in Texas to change its policy. So far, the agency has tried to dismiss their lawsuit, acknowledging that, yes, it can move tenants. But it doesn’t have to. In court documents, it says the law “gives HUD the discretion to determine whether or not to issue such vouchers in that situation.” Beshara says as long as HUD leaves tenants in these properties, the owners keep receiving their rent payments. Even at Forest Cove, a complex that’s half empty, HUD has paid nearly $3 million a year, according to payment records through March 2021 accessed through a FOIA request. “And I think something that should be highlighted,” she says, “is the millions and millions spent by the federal government for substandard housing, when the government has the ability to both change that as well as to let the tenants leave, and live in better conditions.”

Beshara says this also allows owners to make repairs on their own timelines. And as an example, Beshara points to Millennia. Her lawsuit against HUD centers around a complex called Sandpiper Cove near Houston that Millennia once owned. It sold the place after several years of tenants complaining of sewage issues, water leaks and mold. She says there are plenty of other news reports of tenants in Millennia properties waiting in substandard conditions. It only takes a google search to find them. At Bankhead Towers in Birmingham, tenants are suing the company over bed bugs. At Lakeside Homes in Lansdowne outside of Baltimore, residents say they have roaches and their ceilings are collapsing. And in a Kansas City high rise known as Gabriel Tower, tenants protested for more than a year over mold and unstable floors. When the new HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge was in Kansas City, they pressured her to examine the complaints and she agreed. Two of these complexes were also highlighted in an investigation into Millennia by the Houston Chronicle, documenting a pattern of poor living conditions and unreliable management by Millennia across several states.

“This is our mission, we take on properties that have experienced decades of decline, for the purpose of not only transforming the properties, but preserving the affordability of those properties.”

Millennia Public Policy Director Arthur Krauer

Even at Millennia’s renovated properties, housing advocates have concerns. Several of the former Global Ministries Foundation complexes that Millennia has rehabilitated are in Jacksonville, where attorney Mary DeVries runs the housing unit for Jacksonville Area Legal Aid. She pulls up a hundred or so requests for legal help she’s received from two of the properties, Valencia Way and Calloway Cove. She focuses on the calls that came after the renovations. “I think what we’ve seen is that the units that were renovated, there were improvements made, that there were some cosmetic changes,” DeVries says. “Nevertheless we continued to receive similar reports.” The reports detail ongoing issues, among them: mold, sewage issues and roach infestations. She says this is what tenants have relayed to her and her staff. She hasn’t inspected every unit herself. But there’s an aspect of the complaints that almost concerns her more. “I think the troubling part is that when the tenants do make the reports, or even when we make the reports on their behalf, the repairs aren’t quickly made,” she says. “They’re in some cases, ignored, or in many cases ignored.” The management, DeVries says, is still not responsive.

–

Months after we first spoke, Arthur Krauer and Valerie Jerome are back on the phone, still optimistic, but there’s an edge to their responses. When I bring up the news stories showing all the properties where tenants are struggling through Millennia’s delays, Krauer doesn’t address the complaints at each individual complex. He just says those stories don’t represent who Millennia is. “We have 275 properties in which 2% have made news stories,” he says, counting Millennia’s market-rate complexes too. Krauer says several properties that became news stories in the past are now renovated–or “transformed,” the word he frequently uses. He points to Azure Estates, the new name for a property once called Stonybrook in Riviera Beach. He highlights Line Creek, which used to be Englewood in Kansas City. The ones that are still in between, he says, Millennia is not just sitting on them. “This is our mission, we take on properties that have experienced decades of decline, for the purpose of not only transforming the properties, but preserving the affordability of those properties. I’m proud of our mission. I’m proud of the company that I work for. And I stand by our record.”

In that record, he includes the two renovated properties in Jacksonville, where the area’s legal aid nonprofit continued to report lagging repairs and responses. Millennia says they can’t respond to concerns without household names or unit numbers, which I can’t provide. According to Millennia, occasionally tenants experience issues because they aren’t complying with house rules. For example, residents may notice mold or mildew growth because they aren’t opening their windows or running their air conditioning systems, as is required in their lease. Jerome also has her own news stories on hand. She sends me several reports celebrating the renovation in Jacksonville. The reporters highlight the work that has been done: new electrical, new plumbing and new ventilation systems. “Thank you again, the Millennium company for putting your time and your effort into our community,” a resident says at the end. Millennia even connects me with the office of Florida U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, who provides a statement vouching for Millennia’s improvements. “Millennia Housing Development has done tremendous work in rehabilitating Valencia Way in Jacksonville, Florida,” Sen. Rubio wrote. “In August, I visited the property, met with residents, and saw the transformation firsthand – I was thoroughly impressed.”

This “transformation,” Krauer says, is what Millennia intends to bring to Forest Cove. The company is actively working on the complex’s $57 million rehabilitation, he says. Millennia has only delayed the relocation and construction all these months because it hasn’t secured its financing. It needs low-income housing tax credits, a complicated subsidy controlled by the Georgia Department of Community Affairs. But in records I receive through an open records request to DCA, Millennia appears to be the one holding up the process. In emails spanning the more than three years that Millennia’s application has been pending, the company asks for exceptions. It can’t survey tenants because the property is too dangerous, one email from 2018 says. Millennia claims it would need armed guards (this stands out given the tenants’ own concerns about safety.) And when the company says it will provide documents by a certain date, it doesn’t–not for weeks or in some cases months. In one email in April of 2020, a state staffer is so used to the delays that when she hears Millennia intends to complete its application, she jokes “I am betting a six pack of diet coke it won’t come in!” Later in February 2021, a DCA official tells the city of Atlanta that Millennia has provided “little to no responses and incomplete responses” to requests that were already a few months old. Then, in March 2021 and again October 2021, the state imposes deadlines on Millennia: it must submit all outstanding materials or the state will pull its application.

Krauer initially says he’s unfamiliar with any record of slow responses in the tax credit process. “I can tell you that we’ve worked with the utmost urgency, I’ve been working on this project since 2018. It is an extraordinarily complicated transaction with a lot of moving parts, some of which have changed over time because of outside changes.” In a follow up email, Millennia acknowledged there were communication gaps with DCA. It said it worked through those gaps when they arose. The pandemic and its effect on the economy, which reduced projected rents in the Thomasville Heights area, also caused the company to rework its plan for Forest Cove multiple times. A lot of development projects experienced delays for the same reasons, Millennia says.

–

Fall 2021-Winter 2022

As Millennia’s delays stretch into the fall, though, city prosecutors appear to hit their limit. After another round of news stories in September–both Channel 5 and Channel 2 are back at the complex–the solicitor attorneys file another condemnation lawsuit. The office still declines to speak about the apartments. The case is pending as Forest Cove residents wait into the winter and the pressure builds on Ms. Peaches. She keeps picking up trash. Her kitchen floor is still soft even though management put new tile over. And over Thanksgiving, she kills a rat. The rats at the complex make her afraid to cook. Then, in mid-December, she calls me and her voice sounds weak. She says she was in the hospital. “It was like I couldn’t breathe,” she says. The doctor at Grady believed it was asthma. He asked her if her vents had been cleaned out. Ms. Peaches says she doesn’t think they’ve been cleaned out for years. (I see her vents later and at least some are painted shut.) “They got me on some kind of pill, a steroid pill,” Ms. Peaches says. “And they got me on a pump, like when I start wheezing I have to pump myself.” Later, management gives her a small air purifier. But her concerns about air quality in her unit only grow. She keeps visiting the doctor for medicine. And at the end of December, she hears an older neighbor on the northside dies from pneumonia.

In early January, she and Housing Justice League decide to deliver a demand letter to Millennia. As long as residents are still in their units, the letter asks the company to address their health concerns, pay for pest control and provide more security beyond the current guard who sits in a car outside the rental office on Forest Cove’s north side. On a cold, cloudy Friday morning, I meet Ms. Peaches on the street outside the driveway to the rental office. She’s wearing a long sleeve jumpsuit, with her phone in her front pocket, playing music. Housing Justice League’s Foluke Nunn arrives with signs for residents to hold: “Black Tenants Matter.” “We need maintenance now.” “Forest Cove is killing us.” When it comes time to deliver the demand letter, few other residents show up. It’s only Ms. Peaches and two other tenants from the northside, Joeann Mathis and Crystal Teasley. It’s so cold outside, Mathis says they should just go for it. She grabs Ms. Peaches and heads down the driveway to the rental office.

Nearly a year after Millennia bought the property, Ms. Peaches finally believes the promised renovation will happen. That’s not how it turns out. (Alphonso Whitfield/WABE)

“Oh there goes security,” Mathis says right away. As soon as they approach, the lone security guard, who’d still been in his car outside the rental office, gets out and approaches the women. Ms. Peaches announces “We fittin to take a demand letter.” The security responds “You can’t do that.” “Yes, I can!” Ms. Peaches declares back. She and the other residents begin shouting at the security guard. He doesn’t stop shootings or drug dealers, they say, but he wants to stop this? Then, Housing Justice League initiates a chant, “Hey hey, ho ho.” The residents join along. “Justice for Forest Cove!” The security guard turns toward me and says I need to leave the property. I don’t have permission to record here, he says. Ms. Peaches notices this and she steps in between me and him. The two are face to face. “I don’t have anything to do with your building,” the guard says. Ms. Peaches responds, “Well, get out of our way then.” “No I gotta–” before the security guard finishes, Ms. Peaches yells at him, her voice straining, that she can’t breathe and that she’s about to die in her apartment. “You gonna tell me I can’t raise hell?” At this point, several more residents have joined the group. They form a half-circle around the guard, all voicing their own problems with Forest Cove. It’s now him against all their years of frustration. He points to his chest. “Why you hollering at me? I’m the nice guy.” Ms. Peaches says “No you ain’t. You trying to stop us. You Black like us, you should help us.”

The security guard seems nervous. When I try to ask his name, he goes back to the rental office. The residents calm down. Then, Ms. Peaches notices a group of people standing in the street behind us. She walks up the driveway to them. The man claiming to be in charge tells her they’re contractors. He says construction is starting on Feb. 15. “Look I sure hope so,” Ms. Peaches tells him, “See, I’ve been going back and forth to the hospital because I can’t breathe.” It’s a brief conversation. The contractor walks away as soon as he sees my microphone. But Ms. Peaches and the other residents are excited. “Look I see the folks in the rent office hurry and call them out here, you see?” Ms. Peaches says. Afterward, I drive her back to her unit. Talking to journalists and protesting for so long, I ask her if she doesn’t feel like she’s doing the same thing over and over again. Ms. Peaches responds that it does. “But this time I feel different. I feel like they’re hearing my voice. And they’re seeing that we need help out here. So I think I’m seeing something now. I feel a little better.” To her, it finally feels like the renovation will happen. Despite this last year of delayed commitments from Millennia, Ms. Peaches is convinced things at Forest Cove will get better. “It can’t get no worse,” she says. “It can’t.”

–

But no one told tenants, like Ms. Peaches, about the city’s lawsuit to condemn and demolish Forest Cove. No one told them there’d been an outcome in the case, either. Around the new year, shortly before the tenants’ protest, the judge agreed with the prosecutors. He orders Millennia to move all tenants out by March. He also tells the company it has to tear down the whole complex by September. When I ask Millennia about the ruling later in January, Krauer doesn’t make the situation sound too serious. He says the company is working with the city and the state Department of Community Affairs to come up with a solution that everyone can agree with. “So that we can revitalize the project and get residents back to Forest Cove as soon as possible.” But records requested from the state shortly after don’t line up with his positive outlook. In mid-January, after the state learned of the court ruling, DCA division director Jill Cromartie told Millennia in an email it would not work on the project anymore. The state said it would not provide the tax credits Millennia needed for the renovation at Forest Cove. “No further requests in this matter should be considered,” Cromartie wrote. Without the support from the state, it’s clear construction at the complex won’t begin on Feb. 15th. It’s unclear if construction will ever begin at all.

Millennia has appealed the municipal judge’s ruling and says it’s still committed to the redevelopment of Forest Cove but in early February the company acknowledged the current situation. It now says it’s working with HUD and the city to relocate tenants. Neither level of government has provided details on that plan or whether tenants will continue to receive rental assistance. Even if they do, relocation may not deliver the relief tenants have been seeking for so long. According to Housing Justice League, the units some residents viewed as part of the relocation process with Millennia have issues similar to Forest Cove. This isn’t surprising; at low-income apartments throughout Atlanta, there are documented problems with sewage leaking, mold and unresponsive landlords. Foluke Nunn says the tenants she spoke to were counting on a return to a nicer, improved complex. “‘I just want to know that we’re definitely going to be coming back to Forest Cove,” a resident told Nunn. Now, after years of tenants enduring unsafe conditions under the watch of local and federal officials, this is the outcome: the renovation promised to residents is in question. And like the public housing projects Atlanta tore down years ago, Forest Cove may be demolished. I call Ms. Peaches and try to explain this mess the best I can. The news makes her cry. When I ask her what she’s feeling, she says the same thing she’s said to me many times before. “I feel hurt.”