Rosalynn Carter, wife of former president Jimmy Carter, lifelong mental health advocate and co-founder of the Atlanta-based Carter Center, has died at age 96 at her home in Plains, Ga.

Carter was a trailblazer in leading more than five decades of national advocacy for mental health awareness, destigmatization and policy reform –– a cause she picked up as the first lady of Georgia, carried on as first lady of the United States and continued championing as a private citizen through her work at The Carter Center.

“To me, the way we treat people, those living with mental illness in our country, is a moral issue. To neglect those who for no fault of their own are in need—and we do that, we treat them like second-class citizens—runs counter to our values of decency and equality,” Carter said in a 2012 lecture.

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter redefined the American post-presidency through decades of global philanthropy and advocacy.

She is survived by her husband, four children and more than 20 grandchildren.

Plains and Politics

Carter was born Eleanor Rosalynn Smith in 1927 in Plains, Ga., “three years and three miles apart,” as she wrote in her autobiography, from the man who would become her husband of more than 70 years.

Jimmy Carter was the brother of one of Rosalynn’s friends, Ruth. The couple began their romance when Rosalynn was a teenager.

Jimmy Carter went on to attend the Naval Academy.

After marrying in 1946, the couple spent their early years on U.S. Naval assignments in Virginia, Connecticut and Hawaii before moving back home to Georgia to take over management of Jimmy Carter’s late father’s peanut warehousing business, over Rosalynn Carter’s wishes.

“I argued. I cried. I even screamed at him. I loved our life in the Navy and the independence I had finally achieved,” she wrote in “First Lady from Plains.” “Never had we been at such cross purposes. I thought the best part of my life had ended.”

But it was in their small southwest Georgia hometown that the Carters would go on to have national and global impact.

Plains hosted Carter’s 1976 presidential campaign headquarters.

The Carters also returned to their hometown after leaving the White House, and managed the Carter Center’s global advocacy from there ever since.

When Jimmy Carter was elected to the Georgia State Senate in 1962, Rosalynn continued running the family’s business in Plains and began her own career as a “political partner,” as she called herself in her autobiography.

She campaigned for her husband’s gubernatorial and presidential campaigns on her own schedule, crisscrossing the state and country to maximize the campaign’s reach.

Her grandson, former state Sen. Jason Carter, has called Rosalynn “by far the best politician in the Carter family.”

“Something More To Do Than To Pour Tea”

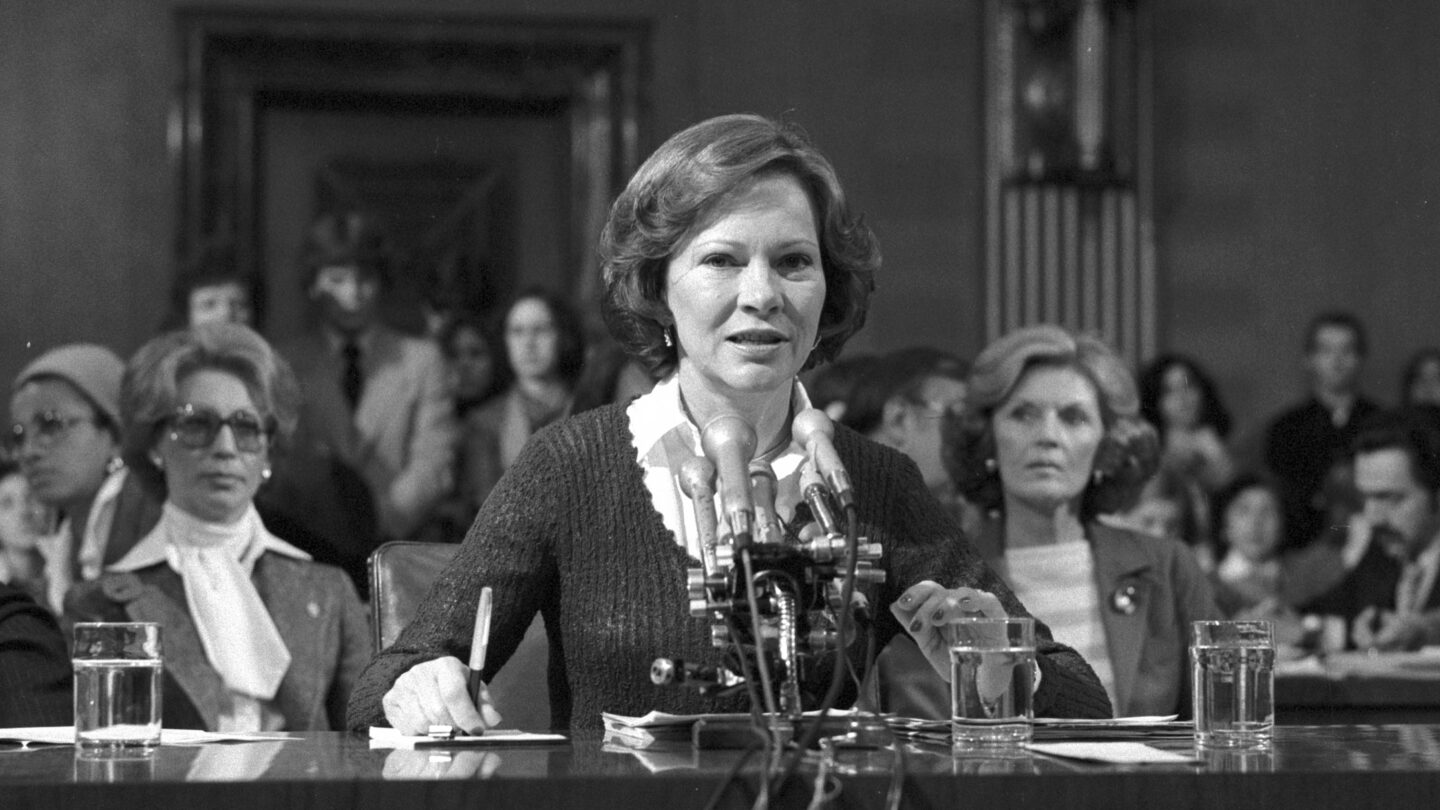

Carter’s tenure as first lady in the Seventies was characterized by political advocacy, especially for people living with mental illness.

And her advocacy persisted well beyond her official political duties.

“There should be no distinction between mental illnesses and other illnesses. They’re all part of the body,” Carter said in 2005.

“The brain is one of the most important parts of the body, and the fact that we have this stigma about having treatment just drives me up a wall. There should be no stigma and no shame.”

“Up until the Carter administration, first ladies had obviously taken on a number of causes,” said Kathy Cade, Carter’s director of projects in the White House, including Carter’s mental health work.

But Carter, Cade said, was really “the first of modern first ladies.”

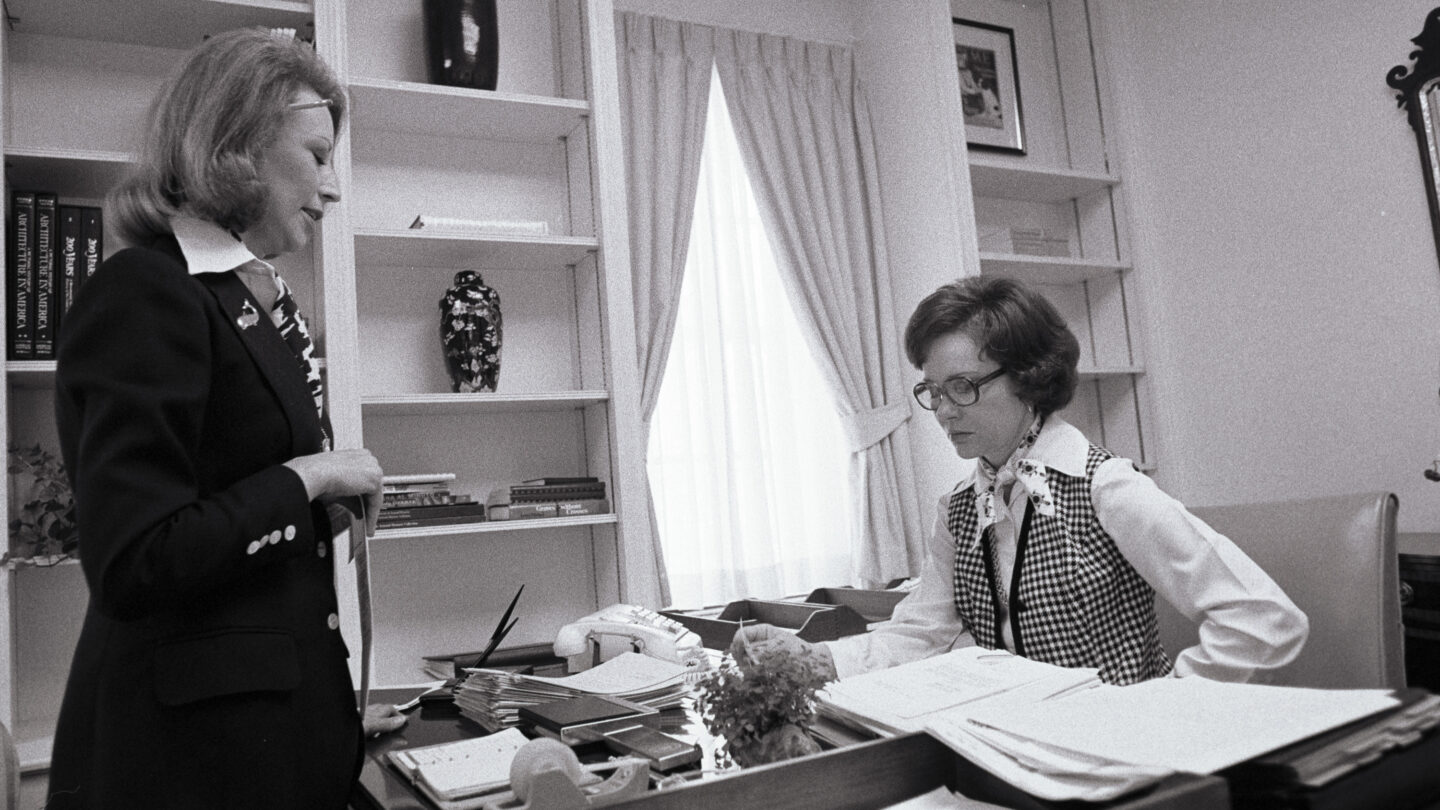

“She was the first first lady to have her own office in the East Wing of the White House. She went to her office every day. She took her work home every night in a briefcase.”

“That was very new,” Cade said. “She brought a level of engagement in substantive issues that was really groundbreaking for that moment in the history of the country.”

Carter first zeroed in on the issue of mental health while campaigning in her husband’s 1970 race for governor of Georgia, hearing citizens’ complaints on the trail.

The campaign coincided with the national movement of the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill, said John Gates, a psychologist who managed Georgia’s largest mental hospital at the time and went on to lead the state’s Department of Behavioral Health.

The intent of deinstitutionalization was “benevolent,” he said, with a goal of offering those suffering with mental illness a better, smaller and more local environment than the larger, existing mental institutions.

“But what tended to happen all over the country was that the populations of those hospitals began to increase for many different reasons,” he said. At the same time, “state legislatures began to pull back on funding as the populations grew in those large hospitals, and all of us have heard about the abuses that took place in these horribly overcrowded places,” he said.

“I campaigned all across the state when my husband ran for governor and I had seen firsthand that adequate services were not being provided,” Carter recalled in 1982.

Amid this climate, Rosalynn took up the cause of mental health advocacy once Jimmy Carter won the gubernatorial election.

“I had always worked; I had always been active in something,” she said.

Carter managed the books of the peanut warehousing business in Plains.

“And I knew that when my husband was elected governor that I had to have something more to do than to pour tea,” she said. “I did not intend to spend my time in the governor’s mansion in that way.”

In 1971, Carter was appointed to her husband’s “Commission to Improve Services to the Mentally and Emotionally Handicapped,” along with mental health professionals, parents and concerned citizens.

“And thus began the learning process that was to cause me great concern for the weak and vulnerable human beings who need love and compassion, and support, and who are often the last to be remembered when appropriations are being handed out in state budgets,” Carter recalled.

“In the beginning, I didn’t know enough about mental illness, or mental afflictions to be able to help in a substantive way with that committee. But I went to all the meetings, and I began to do volunteer work in one of the regional hospitals … and was permitted to work in every area of the hospital.”

During her husband’s governorship, Georgia’s approach to mental health changed, moving away from larger institutions towards support for smaller, community mental health centers.

“In Georgia, what she did was raise the conversation,” said Cynthia Wainscott, a national mental health advocate based in Georgia who worked with Carter for years, “helped people understand the lack of community services, shone a spotlight on the hospitals, and some of the things there that needed to be corrected … And that was just the beginning.”

In four years, as Carter detailed in her book, the number of community centers in Georgia jumped from 23 to 134, the population of Georgians in mental health treatment increased by 56%, while the number of resident hospital patients dropped by about 30%.

To The White House

That state-level advocacy translated nationally once Jimmy Carter won the 1976 presidential race.

One of his first official acts was to create a President’s Commission on Mental Health, with Rosalynn Carter serving as honorary chairperson––“honorary” only because of a legal prohibition on first ladies serving as chairman.

She led a group of people from across the mental health services industry, including those who had experienced mental illnesses themselves.

“It was evident that there had never been an effort of this scale and scope to look at mental health and how to improve mental health care in America,” Cade said.

“It was a number-one priority for her. I would not say that it was the number-one priority for the administration writ large. But because it was her number-one priority, it continued to get priority treatment within the administration.”

In 1978, the commission released a voluminous report, which guided comprehensive new legislation, the 1980 Mental Health Systems Act, designed to finance large-scale community mental health infrastructure.

Then, her husband lost his reelection campaign.

“Instead of tucking her tail and coming back to Georgia and saying, ‘Yeah, well I gave it a shot,’ she doubled down,” Wainscott said of The Carter Center’s Mental Health Program.

Carter’s national platform and “moral leadership” enabled real progress in the mental health space well beyond her time in the White House, Wainscott said.

The annual Rosalynn Carter Symposiums on Mental Health Policy have been crucial, she said, in convening the various stakeholders across the industry and uniting them on certain strategies.

“If she invites a group of mental health advocates to go for a walk in the mud, they will go with her,” Wainscott said in an interview before Carter’s death.

Her post-White House advocacy also translated into the Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellowships to increase awareness and diminish stigma, a focus on behavioral health philanthropy in Liberia, as well as the creation of the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers in Americus, Ga.

“I think it’s fair to say that Mrs. Carter was the right person at the right time. She came along at a time when there were real opportunities to make improvements in the mental health system,” Wainscott said.

“And she had both a passion and the capacity to do something about it.”

Jess Mador contributed to this report.