This story was produced in partnership with ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.

Malik Johnson thought he was doing well after he turned 21 and left foster care, working two jobs to afford his apartment south of Atlanta.

But last fall, everything started to fall apart: His car transmission failed, so he couldn’t reach his second job. He fell behind on rent.

He didn’t know about a federal housing program that could have reduced his housing costs. It’s open to foster youth in all states as long as local government agencies put in an application for the funding. But in Georgia, they didn’t make that request for Johnson — or for almost anyone else.

Instead, at 23, he was on his own. As he faced his mounting bills, the stress got to be overwhelming.

“I was to the point where I was so behind on everything, I just almost stopped caring,” Johnson said.

In Georgia’s foster care system, about 500 young people become adults each year and, sometime between age 18 and 21, they’ll have to make it on their own. Without the safety net the foster care system provides, they’re especially vulnerable to becoming homeless.

That risk is why, in 2019, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development created the Foster Youth to Independence program, which offers between three and five years of rental assistance to young adults who have moved on from foster care. The program is the only long-term federal housing assistance targeted at former foster youth as they navigate adulthood, and advocates hoped it would help prevent situations like Johnson’s from ever happening.

But there’s a catch: The money comes not directly through the federal government, but through the states, which have to apply for and coordinate the funding. WABE and ProPublica found Georgia has barely done that.

Through the program, each local housing authority can request up to 25 FYI vouchers each year. In Georgia, where 20 housing authorities are eligible, that means as many as 500 vouchers could be available, bringing in as much as $5 million in rent money from the federal government each year.

According to HUD’s latest data from last fall, housing authorities in Georgia have received only eight FYI vouchers total since the program began. By contrast, a third of states have each received at least 75 of these vouchers in the program’s first several years. Texas, Florida and Washington have received more than 400 each; California has upwards of 800, helping hundreds of young people afford stable housing. Only five states, all significantly smaller than Georgia, had requested fewer vouchers.

The failure to tap federal vouchers for foster youth in Georgia is a symptom of a child welfare system that has paid little attention to the housing needs of families and children, WABE and ProPublica have found. Previous reporting showed how the state Division of Family and Children Services had put few of its resources toward housing assistance for families in recent years, even as it cited “inadequate housing” among its reasons for removing 20% of children from their parents.

In the case of the FYI vouchers, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has instructed state welfare agencies to work with local housing authorities to ensure the program is used, and in states that have received the most vouchers, child welfare agencies have actively promoted the program and sometimes hired new staff.

But in Georgia, staffers at roughly half of the state’s eligible housing authorities said they hadn’t heard from the state agency about the vouchers in the program’s first five years. A couple of housing authorities said they struggled to get in touch with DFCS to complete the application, while others said they were not eligible to apply because the agency had not helped them to use up other housing funds they needed to distribute before they could tap the program.

DFCS spokesperson Ellen Brown said the staff overseeing services for older foster youth had recently changed and she couldn’t speak to what had happened previously. But she said the agency is now working to strengthen partnerships with housing authorities — efforts that have taken place as WABE and ProPublica started reporting on the issue in recent months and after a local volunteer began pushing the state to expand its use of the FYI program.

Brown also said DFCS staff meet regularly with young people before they exit foster care to “discuss their future plans,” which includes figuring out their housing. “Our team works tirelessly to help them plan and prepare for a safe, stable and successful transition out of care and into adulthood,” she said.

Still, Ruth White, who directs the National Center for Housing and Child Welfare and was central to getting the federal program created, questioned why DFCS wasn’t more aggressive in bringing the vouchers to the state.

“Imagine being an entity that goes in and removes a kid from their house,” White said, “and then not being the agency that’s chomping at the bit to make sure you get a housing voucher for that young person.”

Study after study has shown the high risk of homelessness among young adults who age out of foster care. A 2021 national survey of 21-year-olds who had been in foster care across the country showed that a little more than a quarter of them had been homeless during the previous two years. The same survey also showed similar numbers in Georgia.

For years, child welfare advocates and former foster youth pushed Congress to address this housing crisis.

“We have the numbers, and we have the data,” said Lisa Dickson of the foster youth alumni organization ACTION Ohio in her 2018 testimony to Congress. “What our nation needs is a sense of urgency about this problem.”

HUD already had its Family Unification Program, which provides housing funds to families and youth who’ve been affected by the foster care system. But HUD found that, in the competition for those limited resources, young people were losing out: They received just 5% of those vouchers in 2019, with the rest going to families.

So HUD created the Foster Youth to Independence program, earmarking some vouchers exclusively for young people. As with any Section 8 housing voucher, young people contribute a third of their income toward rent; the federal government covers the rest.

But unlike other voucher programs, FYI requires significant buy-in from child welfare agencies, which must identify eligible young adults and also offer them other support, like job training and financial counseling. That’s why housing authorities and child welfare agencies have to work together to take advantage of the program.

That didn’t happen in Georgia. In Cobb County, northwest of Atlanta, the chief operations officer of the Marietta Housing Authority tried to pursue vouchers in 2020. Mark Wright reached out to the local DCFS director, but he didn’t get the signed agreement from the agency that the program requires. After that, Wright said, “I kind of felt like we were not going to get the kind of buy-in from other agencies to make it successful.” He gave up.

Housing authorities in Atlanta and neighboring DeKalb County already had partnerships with DFCS because they offered the Family Unification Program. But they still had a hard time accessing the FYI funding. In recent years, they said, DFCS hadn’t identified enough young adults or families for the Family Unification Program, and this prevented them from qualifying for the FYI vouchers under HUD’s rules.

In Texas, by contrast, the child welfare agency took the lead in making sure the vouchers reached young people. The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services hired Jim Currier as housing specialist. He, in turn, designated liaisons in each of the child welfare system’s regions, trained them in the rules of the program and incorporated information about the vouchers in the manuals for foster youth aging out of care. The child welfare agency now has 40 partnerships, and DFPS initiated 38 of them.

Currier said vouchers have transformed the lives of some of the young people they’ve gone to. “They now have a safe, permanent home; they can begin to work on their well-being; they can work on their education,” he said.

Recently, in Georgia, DFCS and housing authorities began talking about how to serve more of those former foster youth — thanks in part to the work of one persistent volunteer.

Anne Carelli got to know teenagers in foster care when she volunteered at a group home in Atlanta. As they aged out of the system, she saw some of those teenagers end up homeless. So when she learned about the FYI vouchers a few months ago, she couldn’t believe Georgia wasn’t using them.

“To have housing vouchers for youth aging out of care — that is an incredible opportunity for all of us to come together and figure this out,” said Carelli, who has founded a nonprofit called Up3 to help connect young adults with the resources they need.

Carelli said she has sent more than 60 emails to housing authorities, public officials and DFCS to kickstart meetings about getting vouchers to young people she knows who qualify.

She’s hoping one of them will be Johnson, who she met through the group home. He’s still spending nearly four hours every day on buses and trains to get to work. The assistance would help him save for another car.

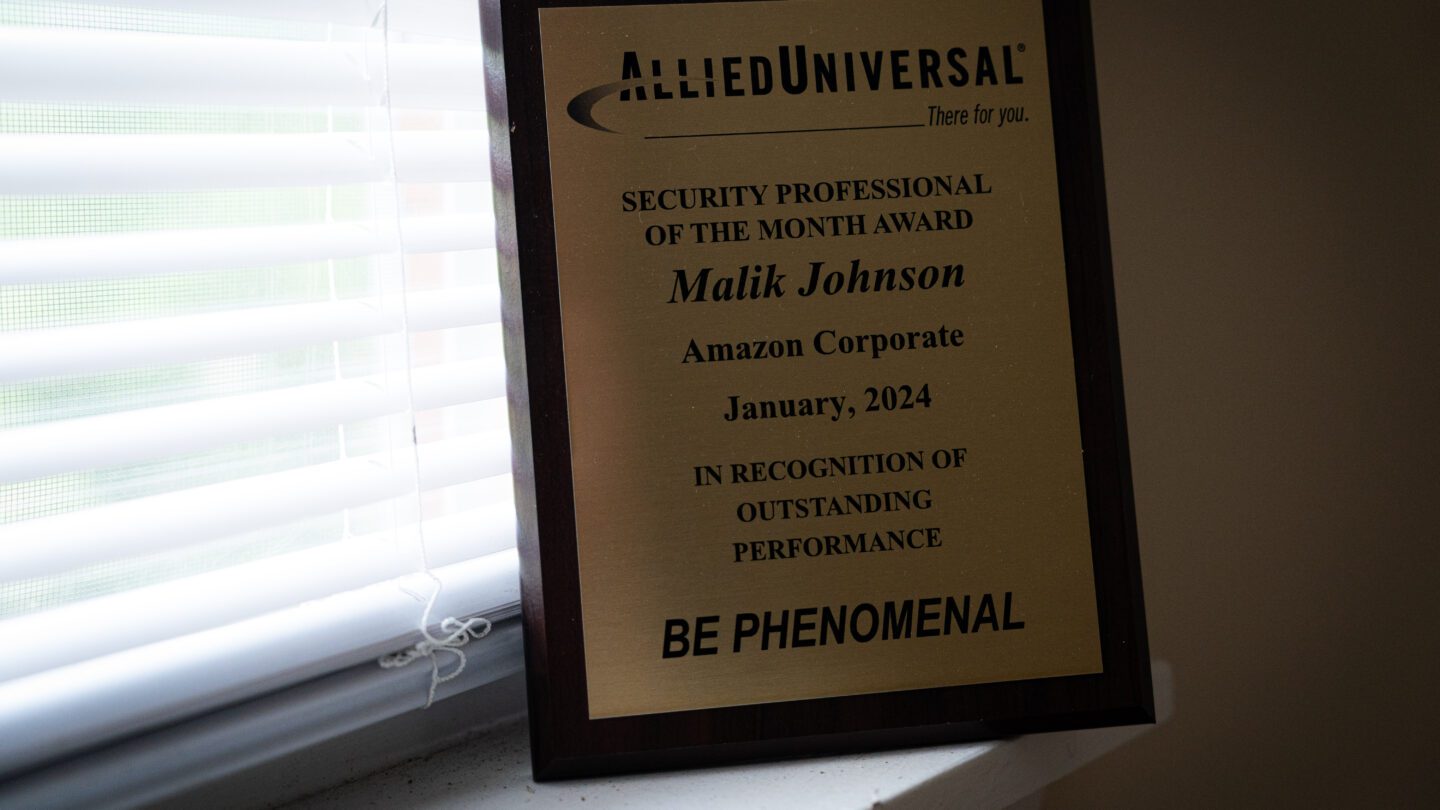

Johnson knows the value of a little outside support. Last fall, Carelli loaned him the money that allowed him to make up his rent until his income was stable again. As much as he’s tried to be responsible for himself — keeping his apartment vacuumed and clear of clutter, earning an employee of the month plaque from his job — he faced a crisis he couldn’t handle on his own.

“But I had help,” Johnson said. “And that was the best part about it too — being able to receive help when you need it.”