Think Tarzan and the Golden Lion needed a different ending?

Perhaps you want to adapt Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet into a graphic novel.

Or maybe you want to have a go at incorporating Robert Frost’s poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” into a virtual choir piece, as composer Eric Whitacre once did before encountering a copyright snag that killed the project.

Well, the chance to dust off these three — and countless other works originally copyrighted in 1923 — has arrived. A large body of films, music, and books from that year entered the public domain on Jan. 1, the first time that’s happened in 20 years. And that means they can be used according to the will of new creators who wish to adopt or adapt them.

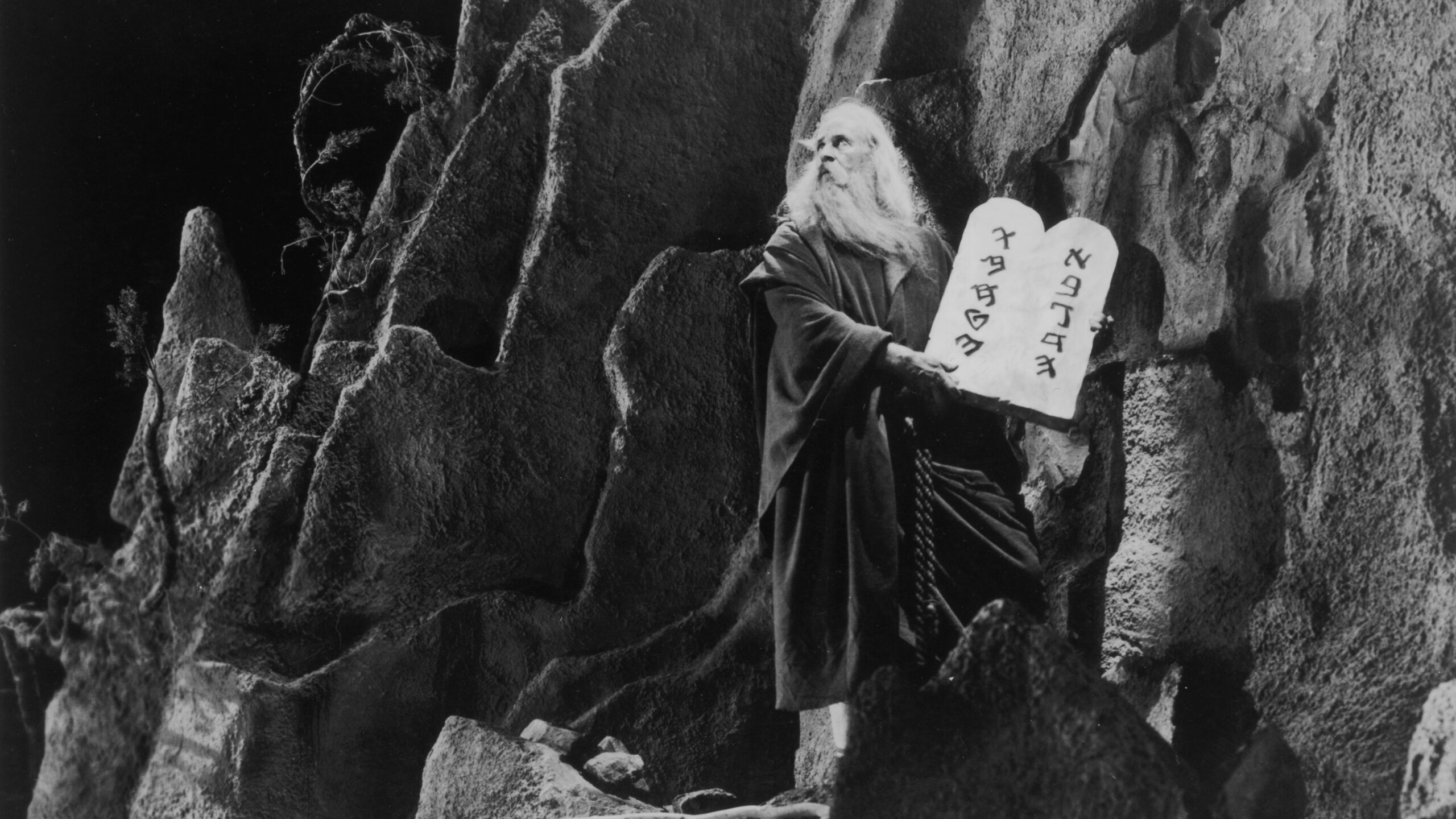

The list includes films like Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, songs like Jelly Roll Morton’s “Grandpa’s Spells” and poetry collections like e.e. cummings’ Tulips and Chimneys. All these works were originally set to enter the public domain in 1999, but then Congress extended the copyright term by an additional 20 years for works between 1923 and 1977 — leading to that 20-year hiatus.

Those lengthy copyrights can be a barrier to the creation of new art. “Copyright has been overextended so many times, largely at the behest of major copyright holders,” says author Naomi Novik. “Even though what that actually does is inhibit people from creating new works and sharing these older works.” Novik is a founding member of the Organization for Transformative Works, a nonprofit that focuses on preserving fan fiction and art — that is, work created by fans, based on characters and worlds from their favorite written works, film, and TV, which can occasionally come into conflict with copyright law.

“For a character to live, that character has to belong to the audience,” says Novik. “Works of art are meant to nourish our collective understanding; they’re meant to nourish our conversation.” As Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain notes, “Many of these works are lost entirely or literally disintegrating (as with old films and recordings), evidence of what long copyright terms do to the conservation of cultural artifacts.” But the surviving works can now be refurbished.

“I’m interested to see what people will do with these things.” says Madeline Miller, author of Circe and The Song of Achilles — each novel an adaptation of Homer (whose centuries-old work isn’t protected by copyright, though some translations may be). “I imagine that there will be some really extraordinary pieces of art that may come out of it. I love that you will have an explosion of new editions of these works.”

Novik says that the impulse to re-imagine art is innate. “That kind of process of imagination is just something that our brains do. It doesn’t matter what law you put around it, our brains are still going to do it,” she says.

Inevitably, the spring of adaptations will bring about bad versions of these classic works. As Blake Hazard, great-granddaughter of F. Scott Fitzgerald, told The New York Times, “I hope people maybe will be energized to do something original with the work, but of course the fear is that there will be some degradation of the text.”

Miller, who adapted Homer, does worry about the possibility of betraying the texts. But as she was working on Circe, she says, “I came to the understanding that I can’t hurt Homer. He’s fine. Whatever I do, that’s just my response to him. But the original text will be just fine.”

Besides, she adds, bad versions and good versions of art tend to compel fans to check out what inspired the work in the first place. “I feel like retellings always point you back to the original. You want to listen to both parts of the conversation,” Miller says. “All boats rise.”

Novik says the opportunity to adapt is necessary for art to advance. “Nobody wakes up and writes a classic work of literature as the first thing they ever set their pen to paper,” she says. “You have to make bad art before you can make good art.”

Now that these works have entered the public domain, it is possible to find them online free of charge — and to engage with them in whatever way moves you. “You don’t hurt a work by responding to it,” Novik says. “I think that being unread, being unseen, falling into silence, that is the common fate of any work. And that is the real death of any work of art.”

Duke Law’s entire list of works that entered the public domain this year can be found here.

Milton Guevara is a news assistant at the Arts Desk.

Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))