“I said, well, what is that?” Lawson recalled. “He said, it’s where you talk to people about what they saw of a person’s face that perpetrated a crime, you just sit down and get the description from them and draw it on the paper.”

Lawson continued working at police departments across Georgia until 1996, when she joined the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. The GBI had asked her to do a sketch of the Olympic bomber Eric Robert Rudolph and were so impressed that they made a job for her.

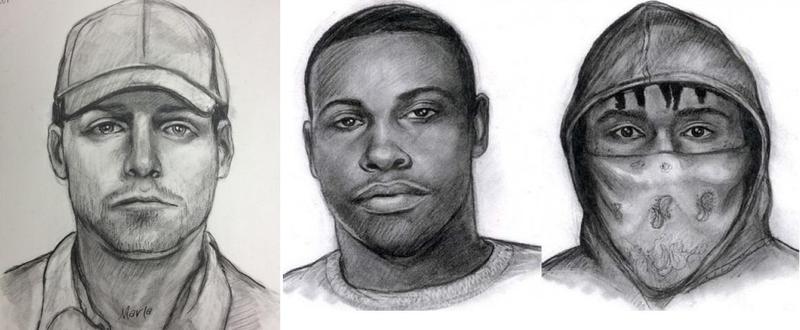

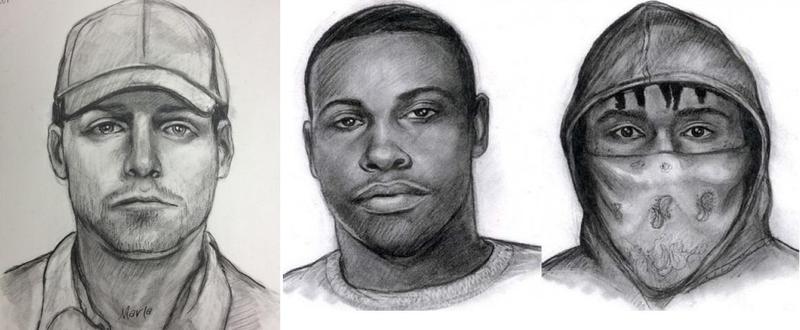

Lawson’s drawings are realistic in size. She pays attention to skin tone and hair. She even draws the neck.

Not all forensic artists think this amount of detail is necessary for good composite sketches, and Marla’s style has gotten some criticism because she makes the perpetrator look good.

“As I think one gentleman said, why does she make her sketches look like polished portraits?” Lawson said. “And, I’m thinking, why wouldn’t I? Why not give that perpetrator him own glamor shot?”

And those glamor shots have helped solve cases. Lawson retired in 2012, ending a 37-year career with an estimated 10,000 faces drawn in charcoal.

Along with composite drawings, forensics artists are expected to reconstruct the faces of the unidentified deceased, which are usually in a rather sorry state of decomposition.

Using the skull and bones, Kelly Lawson tries to identify the age, the race and the tissue depth of the deceased, and then builds a model on top of the skull with clay.

Kelly Lawson is Marla’s successor – and, her daughter.

Like her mother, Kelly Lawson never imagined she would be a forensic artist. Art had always been a part of her life, though. She went to college on an art scholarship.

According to Marla Lawson, when she was finally ready to relinquish her position to the younger generation and retire, nobody who wanted the job was good enough. So, she asked her daughter to give it a try. They trained together for about 13 months, which was taxing for both of them.

“She’s just kind of rough,” Kelly Lawson said of her mother. “Rough around the edges. She tells you how she feels. She knew she could tell me exactly what she wanted me to do and knew she could be just as coarse as she needed to be.”

Beyond producing high quality sketches, Kelly Lawson spends a lot of her time in her car, traveling to police stations across the state and then asking victims to recount the most traumatic event of their life.

When Marla Lawson started as a forensic artist in the 1970s, she developed her own method for composite drawing, a method that Kelly uses for her own sketches.

After traveling to a police station to meet the victim, Kelly Lawson pulls out a book of photos.

“If I had to draw a white male, it would be a book full of white males faces,” she explained. “Anything from celebrities, to dramatic black and white portraits, to mug shots in the 70s and 80s.”

The victim will look through the photos and pull aside ones that look like the perpetrator.

“And they’ll go,” Kelly Lawson continued, “his eyes were like this guy. Or I remember his hair like this guy. And you see this guy’s expression? It just kind of looked like that.”

She takes the selected photos and crafts them into a sketch. She tries to have a draft of the sketch within 30 minutes and works with the victim to modify it until it looks more like the perpetrator.

Kelly Lawson said, “I ask them, on a scale of one to ten, if ten is what you remember, I won’t call it quits until we get at least an eight out of ten.”

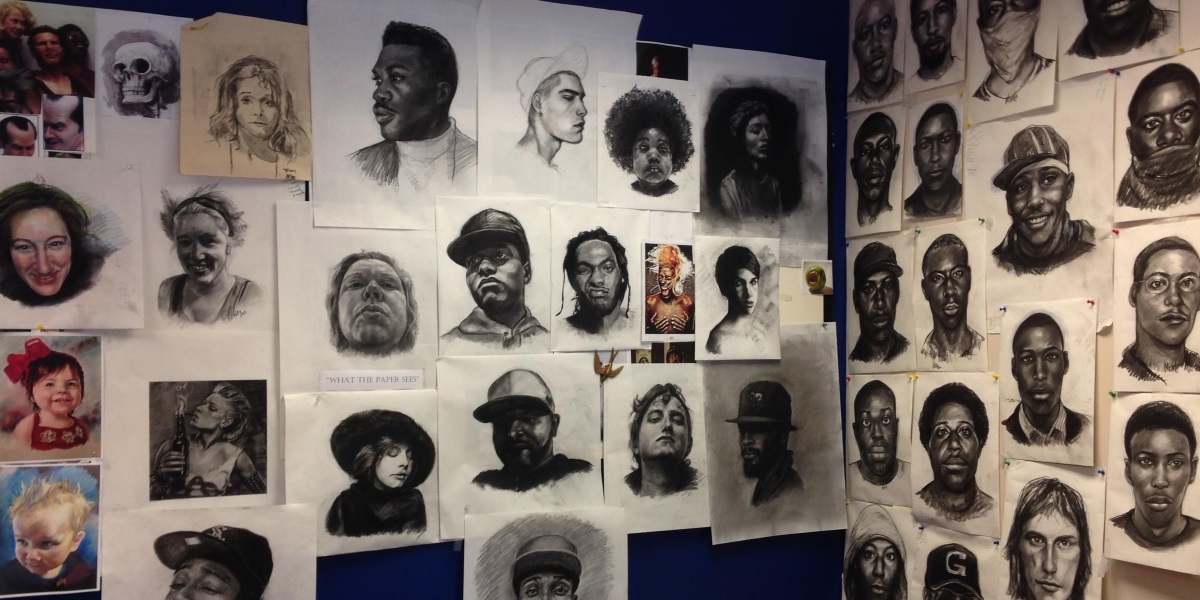

Two walls of her office at the GBI are covered in sketches. One wall has some of Kelly Lawson’s favorite sketches that she’s done in her spare time to keep in tip-top drawing shape.

The other wall has some of Marla Lawson’s sketches. It’s Kelly Lawson’s “inspiration wall.”

“Marla just is hugely inspiration. For anyone who had the opportunity to watch her work, she could take a drawing a person, she could take picture of a person to the victim’s specifications and get it done in 20 minutes,” said Kelly Lawson reverently. “She never had to pull out an eraser. The whole time she was cracking jokes and talking about crazy lunacy, and entertaining a whole crowd of people.”

“Marla is a very talented artist,” GBI Director Vernon Keenan said, “and I think that her work and Kelly’s work more accurately portrays what a person looks like.”

Marla Lawson said in an ideal world, there would be security cameras on every street corner, but for the most part, crimes are committed without any cameras around.

She pointed out, “What if a man comes in your home and like that classic scenario, like in Psycho and he stabs the woman in the shower. I mean, there are no cameras in there.”

Unlike crime shows like “24” and “CSI,” there isn’t some magical face recognition software that saves the day.

There is software that can make a composite image without an artist. It takes different photos and stitches the features together, but the image looks weird.

Kelly Lawson explained, “What you get is this semi realistic, somewhat photo-like image that people look at and they aren’t sure if it’s a photo of a person or a composite of a person so they are not able to use their imagination.”

With security camera footage or with these software images, the image is often too lifelike for people to even consider someone if the suspect doesn’t completely match the image.

But Kelly Lawson’s hand-drawn images are also the subject of scrutiny. She has received a lot of criticism on Facebook for some of her composite drawings, which have been condemned as racist.

She drew a suspect that a victim described as “Dr. Dre with big lips.” Another drawing she did resembled TI, and the rapper himself held up her sketch in a YouTube video.

“The victim picked out a picture and told me to draw it just as it was and it just happened to be a celebrity,” Kelly Lawson said of the sketches.

She said that her role as a forensic artist is to act as a vessel for a witness’ memory, but that can be a problem because witnesses have their own biases when describing a suspect:

“You hate to admit it, but it’s true, if I’m a Caucasian female and I see a young Hispanic male come up to me, it’s easy for me to generalize him in terms of a certain race. So it’s going to be harder to draw him than if a white male came up to me and starts communicating with me.”

Like mother, like daughter, Kelly and Marla Lawson have become hyper-aware of crime through their job.

Missing persons, rape, murder, theft—they have seen it all. At her suburban home, Marla Lawson has multiple locks on her front door and wants to install security cameras in the yard.

And with more security cameras coming along in the digital age, the forensic art profession could be threatened.

After all, one of the first investigative steps for the GBI is to look for digital evidence like iPhone photos or surveillance footage.

“If we got video footage of the suspect that’s perfect,” GBI Director Keenan explained. “We don’t have to go to the composite drawing. But that’s not the case for most of the crimes.”

According to Keenan, composite rendering software is always the second choice.

“I think the public and law enforcement prefer a portrait of the perpetrator as opposed to what looks like computer drawing,” Keenan said.

Even if the GBI used this software, they would still need someone to talk with the victim for information.

And that’s another important part of the job of a forensic artist: to be compassionate and empathetic with people. Police departments have yet to develop a technology that can do that.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))