On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It sent approximately 70,000 U.S. citizens into internment camps for years, including a very young George Takei.

“I was five years old at the time,” recalls the actor. “It was a terrorizing morning I will never be able to forget. Literally at gunpoint, we were ordered out of our home.”

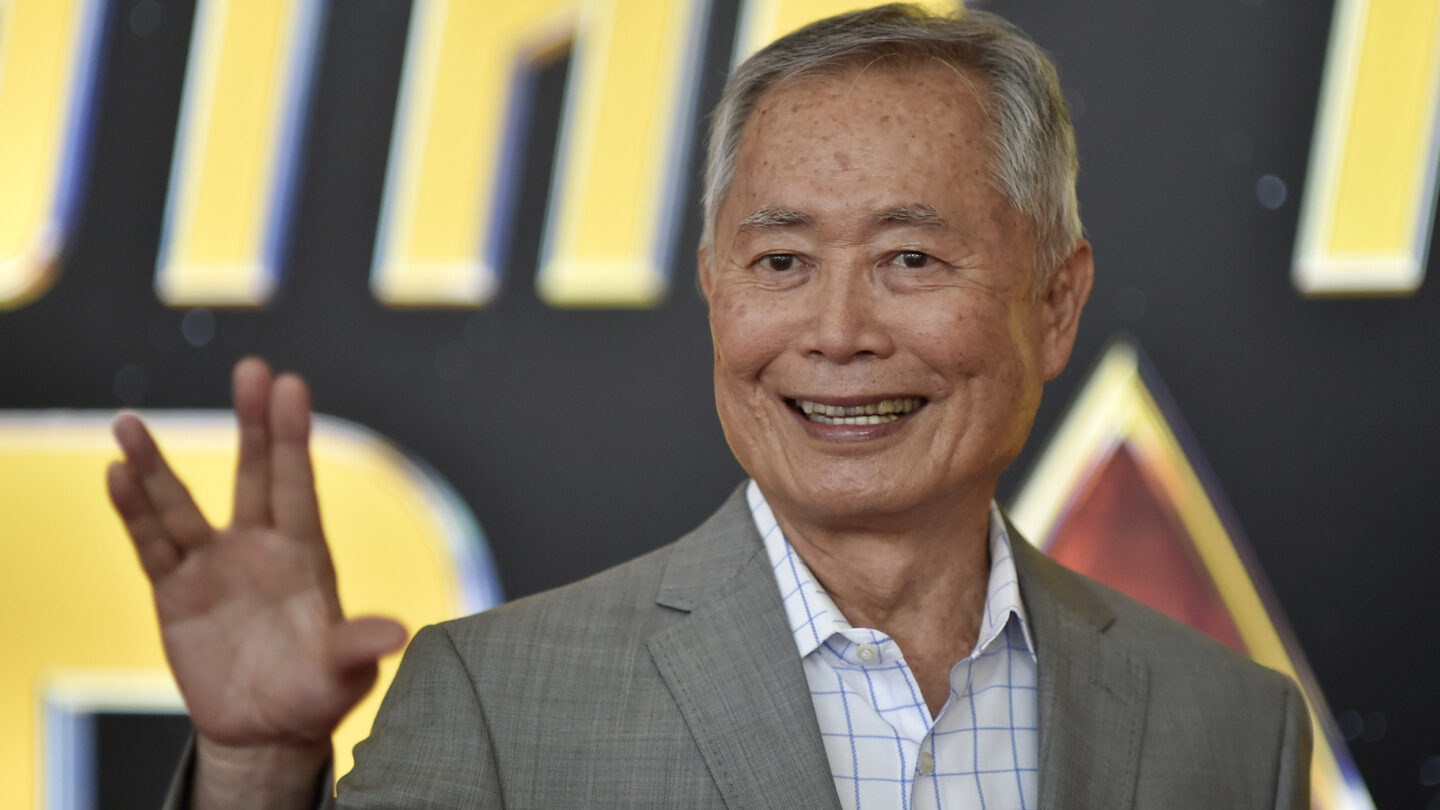

Best known for playing Mr. Sulu in the original “Star Trek,” Takei is a longtime activist whose causes have included LGBT rights and reparations for Japanese-American survivors of internment camps. In 1942, his family was sent to Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas, then later to Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California. The Takeis were among thousands of Americans who lost their homes, farms, stores, cars, churches, temples and countless belongings because of xenophobia and racism.

“Some people had their life savings taken from them just because we looked like the people who bombed Pearl Harbor,” Takei says.

Collectively, Japanese-Americans forced into internment camps lost more than $6 billion dollars adjusted for inflation, according to an estimate from the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. This is a story George Takei has told over and over: in a memoir, on Broadway, and to members of Congress in 1981. Takei testified at a hearing as part of an effort to push for redress.

“I urge restitution for the incarceration of Japanese-Americans because that restitution would, at the same time, be a bold move to strengthen the integrity of America,” Takei told a federal commission.

Working with other activists, he succeeded. In 1988, then-President Ronald Reagan, a Republican, signed legislation to give $20,000 and a formal apology to Japanese-Americans who’d survived internment.

George Takei dedicated the money he received from the federal government to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. Now, he’s a passionate supporter of redress for descendants of enslaved people in the U.S.

“For us, it was four horrific years,” Takei says. “For African-Americans, it’s four torturous centuries.”

Such solidarity warms the heart of Andre Perry, a renowned scholar of repatriations and a fellow at the Brookings Institute. “George is exerting a level of patriotism that we don’t see today,” he says. “You can be of a different persuasion but share a common cause, a common purpose. I may not be related to you, but civically, I’m your brother. I’m your sister. I’m your friend.”

“If he were around, I’d give him a big hug,” he adds.

Perry notes that the historic experiences of Black Americans and Japanese-Americans are obviously very different, but ultimately, he says, it’s about getting to a similar place. “Even with slavery, its not impossible to find out who deserves reparations,” he points out. “And it’s clearly not impossible with redlining and criminal justice atrocities. That was not that long ago. We can identify who is injured and who deserves how much. It’s really about willingness.”

Last year, composer Kenji Bunch set George Takei’s testimony before Congress to music. His piece, called “Lost Freedom: A Memory,” premiered at the Moab Music Festival. Takei himself provided narration. “I believe that American today is strong enough and confident enough to recognize a grievous failure,” he reads in his inimitable baritone. “I believe that it is honest enough to acknowledge that damage was done. And I would like to think it is honorable enough to provide proper restitution to the injury that was done.”

Does George Takei still believe that in 2022? He says he does.

He says he believes America – and Americans – are still strong and honorable enough for the best of this country’s ideals to prevail.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))