This story was updated at 6:37 p.m.

Following the deadly shooting at Apalachee High School in Winder, Georgia, some parents have raised concerns about personal device bans in schools that could delay communication from students in the event of an emergency. However, some Georgia educators and parents say the bans should stay in place, arguing that personal devices could be a distraction during a serious emergency.

The Sept. 4 shooting took place in Barrow County, about an hour away from Atlanta. A 14-year-old student allegedly shot and killed four people at Apalachee High School, and nine others were hospitalized for their injuries.

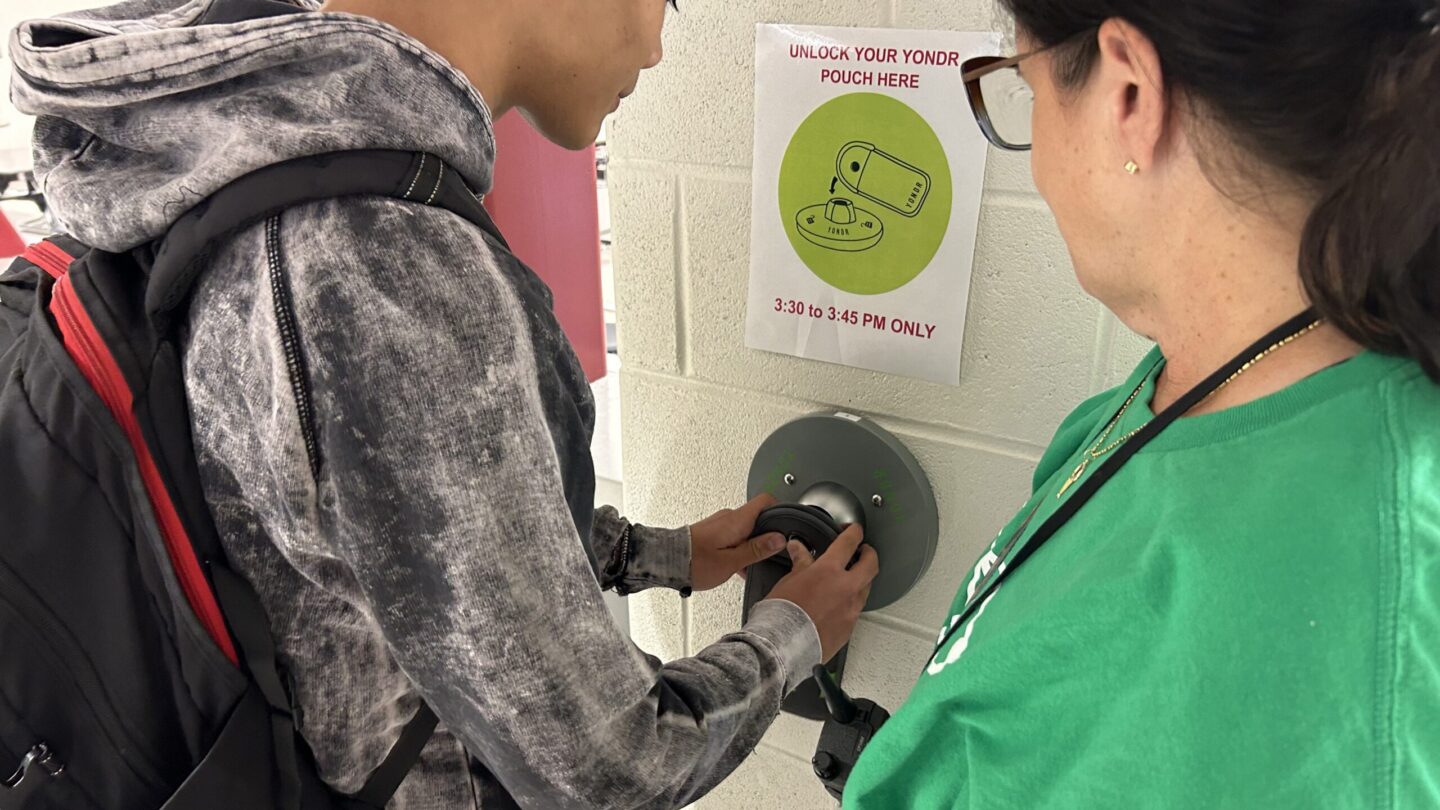

Across metro Atlanta, some schools have instated bans on the use of personal devices, including cell phones, smart devices and laptops, to curb distractions during school hours. Some require students to put their devices in a pouch, which can only be unlocked with a certain magnet.

Kimberly Dukes, the co-founder and executive director of the education equity nonprofit Atlanta Thrive, said she does not support a complete ban on personal devices. Every student’s situation is different, she said, and she needs to be readily accessible for her child in case of a mental health emergency.

“When he begins to have a crisis, everybody is not a safe person to him, and a lot of times, he can hear my voice on the phone and he will calm down,” Dukes said.

She’s also in favor of creating a middle ground between educator and parent priorities, such as keeping the devices in a place where teachers can see them.

“How do we innovate the classroom and make this a part of the learning environment?” she said. “So it’s not taking total control away from children, but it’s also a teachable moment, teaching them there’s a time and there’s a place.”

Grant Rivera is the superintendent of Marietta City Schools, which passed a personal device ban starting this fall for Marietta Sixth Grade Academy and Marietta Middle School.

“We reminded families that in the event of an active shooter, our number one priority in class is to keep kids as safe as possible,” Rivera said, referencing a recent Marietta City Schools town hall following the shooting.

“We want children listening to the directives of a caring adult who’s been trained on how to respond in an emergency. What I don’t want — and first responders and law enforcement will confirm this — is I don’t want children missing the directives of caring and trained staff because they are trying to text their parents.”

Midtown High School has also enforced a personal device ban. After the shooting, Midtown’s principal, Betsy Bockman, issued a statement addressing parents’ safety concerns.

“I know many of you had anxiety today about phones in pouches. Understandable. While it raised your anxiety it kept anxiety, misinformation, disruption and distraction here at Midtown to a minimum,” wrote Bockman.

The principal added that she would communicate with parents via Infinite Campus Parent Portal in the event of a serious emergency and notify them of any alternative pickup instructions. If students need to evacuate the building, students can unlock their pouches containing their devices.

Jane Smith, who has two children who attend Midtown, praised Bockman’s response and support for the personal device ban. She said she understands parents’ “impulse” to want to immediately contact their kids, but added that parents only feel that need because they have gotten used to pervasive cell phone use.

“I think the kids would be better off having their full attention on surviving, listening to their teachers, following the protocols and helping their group that they’re with manage the space they’re in rather than trying to communicate, because parents can’t get in there and help,” Smith said.

Jenifer Keenan, who also has two children who go to Midtown, said students can still message their parents on their school-issued computers via Schoology, a learning portal.

“I don’t think that there’s any text that I could provide in an emergency like that that would improve the safety of my kids at school,” she said.

Keenan supports the ban on phones, but added that school-issued laptops have been overly restrictive by, for example, not allowing students to send emails outside of the Atlanta Public Schools system, even during after-school activities that may require outside research or contacts.

Overall, both parents cited the educational and developmental benefits associated with the ban. Smith said access to cell phones at school “facilitates addiction” to screens, especially for adolescents who are still developing and learning to control their habits.

“I really like the complete ban because it means when they’re finished with their work in class, they’re not scrolling TikTok and doing things that aren’t enriching their brain and aren’t helping them forge social connections,” Smith said. “Maybe they’re talking to a friend or catching up on their homework or actually relaxing and not jamming more content into their brain.”

Schools have also adopted device ban policies due to concerns over the effects of social media and cell phone use on adolescents’ mental health. U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory for social media use last year, warning of the negative effects it could have on the mental health of children and adolescents. Murthy is now calling for a surgeon general’s warning label on social media platforms.

Following the shooting in Barrow County, legislators have also called for greater mental health awareness and response. Tiffany Fick, chief of strategy at the Atlanta-based organization Equity in Education, said limiting access to personal devices in schools could curb the mental health effects associated with excessive social media use.

“I think that you can kind of make some connections between the mental health the students in this generation are experiencing from being on the internet a lot, being on social media, to why we have school shootings to begin with,” Fick said.

To “break that cycle,” Fick said schools should not change policy reactively, but rather with the students’ holistic well-being in mind.

“I think that we have to slow down and take just a really deep look and bring in the people who understand the nuances of these situations so that we aren’t making blanket policy statements or changing policy just to appease parents or just to address these moments, but we’re thinking long term and really centering students at the heart of all the issues,” she said.

Not all personal device bans look the same from school to school.

Instead of having one or a few centralized locations where students can access a magnet to unlock their device pouches, Marietta Middle School and Marietta Sixth Grade Academy have magnets in every classroom, so teachers could unlock students’ phone pouches once it was safe to do so, according to Rivera, the superintendent.

Nevertheless, some believe policies affecting whether parents would be able to reach their children during a serious emergency don’t solve the prevalence of school shootings.

Lisa Morgan, the president of the Georgia Association of Educators, said she believes that the personal device ban is not the problem, adding that people should advocate for gun control so that parents would not have to worry about their kids’ safety in the first place.

“The solution is to solve the gun violence problem so that no child ever needs to be in the situation that they need to send that text to their parent,” she said. “That is our number one goal in our schools: that students are, number one, safe, but that they are there and they are learning, because that’s what school is for. Tying these two issues is not how we solve either of the issues.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentified Tiffany Fick’s title. She is the chief of strategy at Equity in Education.