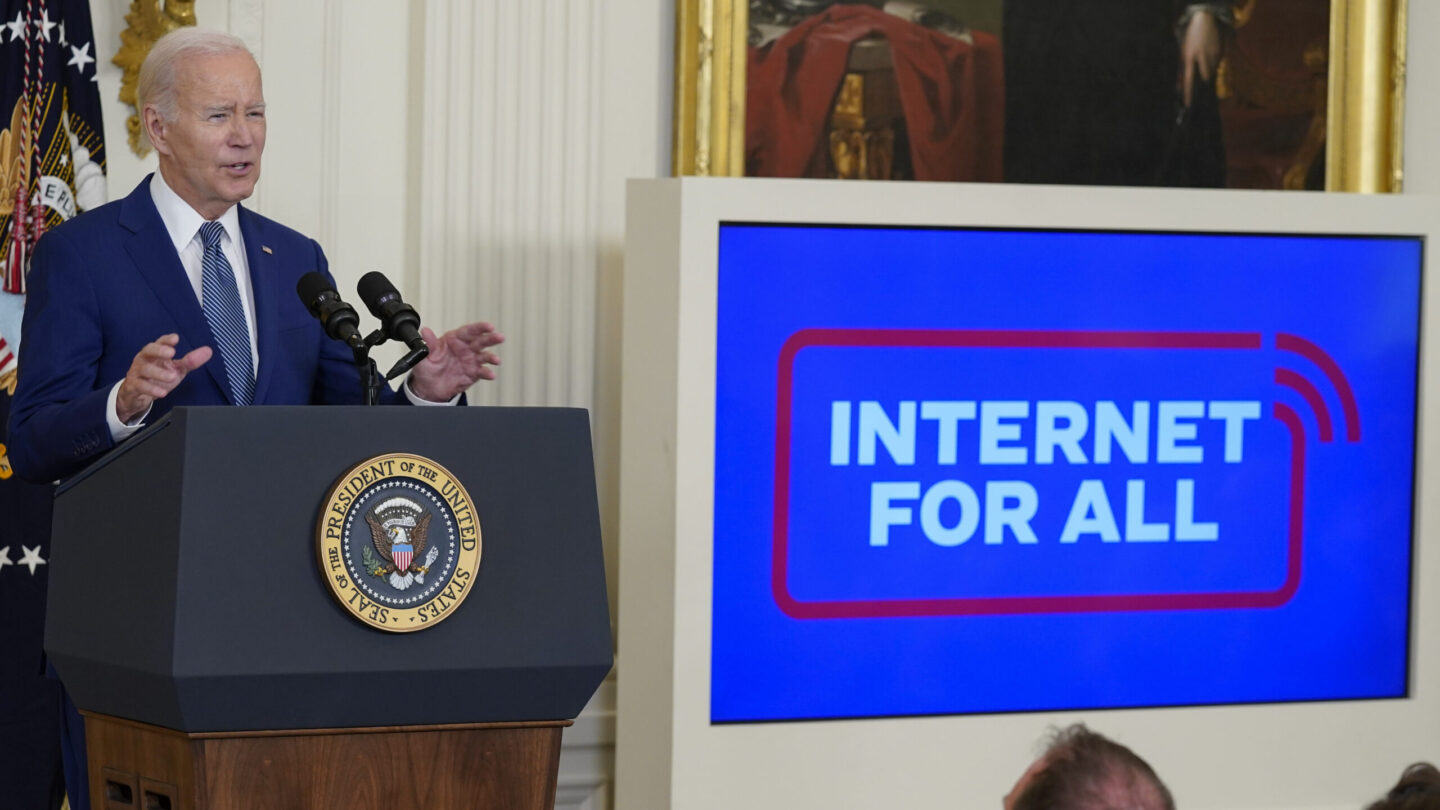

President Joe Biden on Monday announced that more than $40 billion would be distributed across the country to deliver high-speed internet in places where there’s either no service, or service is too slow. The allocation includes $1.3 billion coming to Georgia — the ninth-highest award of any state.

“These investments will help all Americans,” Biden said. “We’re not going to leave anyone behind.”

Georgia Democrats trumpeted the announcement.

“This is great news for our state,” said U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock. “This federal investment means life gets easier for hundreds of thousands of Georgians, and provides the tools and infrastructure our communities need to be competitive in the 21st century,”

U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff said he and Warnock have made expanding high-speed internet access across Georgia a top priority since taking office.

“Through the bipartisan infrastructure law, we are now delivering an unprecedented investment in broadband access for families and businesses across the state of Georgia,” Ossoff said.

U.S. Rep. Lucy McBath of Georgia noted that Georgia families rely on broadband access “for their jobs, their schoolwork and keeping in touch with loved ones.”

“I’m thrilled to see these federal funds come home to Georgia,” she said. “Expanding our state’s access to broadband is critical for the economic success of our small businesses, the educational future of our children and the pursuit of equity in our communities.”

News of the $1.3 billion broadband boost follows a January announcement by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp that he was directing $234 million in federal COVID-19 relief fund to construct broadband internet to rural locations that don’t currently have connections.

With Monday’s announcement, the Biden administration is launching the second phase of its “Investing in America” tour. The three-week blitz of speeches and events is designed to promote Biden’s previous legislative wins on infrastructure, the economy and climate change going into a reelection year. The president and his advisers believe voters don’t know enough about his policies heading into his 2024 reelection campaign and that more voters would back him once they learn more.

Biden’s challenge is that investments in computer chips and major infrastructure projects such as rail tunnels can take a decade to come to fruition. That leaves much of the messaging focused on grants that will be spent over time, rather than completed projects.

The internet access funding amounts depended primarily on the number of unserved locations in each jurisdiction or those locations that lack access to internet download speeds of at least 25 megabits per second download and upload speeds of 3 Mbps. Download speeds involve retrieving information from the internet, including streaming movies and TV. Upload speeds determine how fast information travels from a computer to the internet, like sending emails or publishing photos online.

The funding includes more than $1 billion each for 19 states, with remaining states falling below that threshold. Allotments range from $100.7 million for Washington, D.C., to $3.3 billion for Texas.

Biden said more than 35,000 projects are already funded or underway to lay cable that provides internet access. Some of those are from $25 billion in initial funding as part of the “American Rescue Plan.”

“High-speed internet isn’t a luxury anymore,” he said. “It’s become an absolute necessity.”

More than 7% of the country falls in the underserved category, according to the Federal Communications Commission’s analysis.

Sen. Joe Manchin, who Biden called out as a “friend” during today’s announcement, celebrated the $1.2 billion West Virginia will receive to expand service in the rural, mountainous state of around 1.8 million.

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo joined Manchin at a press conference after Biden’s announcement and said West Virginia’s allotment would be enough money to “finally connect every resident.”

“When I say everyone, I mean everyone,” she said. Raimondo said the reason that hasn’t happened in the past is because it’s expensive to lay fiber in a rural or mountainous area. “And so the internet providers haven’t done it — it doesn’t make economic sense for them,” she said. “What we’re saying to them now is, ‘With this money, $1.2 billion to connect about 300,000 folks in West Virginia, it is plenty of money to get to everyone.'”

Congress approved the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment program, along with several other internet expansion initiatives, through the infrastructure bill Biden signed in 2021.

Earlier this month, the Commerce Department announced winners of middle mile grants, which will fund projects that build the midsection of the infrastructure necessary to extend internet access to every part of the country.

States have until the end of the year to submit proposals outlining how they plan to use that money, which won’t begin to be distributed until those plans are approved. Once the Commerce Department signs off on those initial plans, states can award grants to telecommunications companies, electric cooperatives and other providers to expand internet infrastructure.

Under the rules of the program, states must prioritize connecting predominantly unserved areas before bolstering service in underserved areas—which are those without access to internet speeds of 100 Mbps/20 Mbps—and in schools, libraries or other community institutions.

Hinging such a large investment on FCC data has been somewhat controversial. Members of Congress pressed FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel about inaccuracies they said would negatively impact rural states’ allotments in particular, and state broadband officials were concerned about the short timeline to correct discrepancies in the first version of the map.

The second version of the map, which was released at the end of May and used for allotments, reflects the net addition of 1 million locations, updated data from internet service providers and the results of more than 3 million public challenges, Rosenworcel, who in the past has been a critic of how the FCC’s maps were developed, said in a May statement.

AP reporter Leah Willingham contributed from Charleston, West Virginia.

Harjai, who reported from Los Angeles, is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.