The Georgia Supreme Court heard arguments Wednesday in the case of two Democratic elected officials arrested while protesting at the state Capitol.

Lawyers representing U.S. Rep. Nikema Williams and Atlanta state Rep. Park Cannon said the laws used to arrest them are vague, overbroad and violate their free speech rights under the state Constitution.

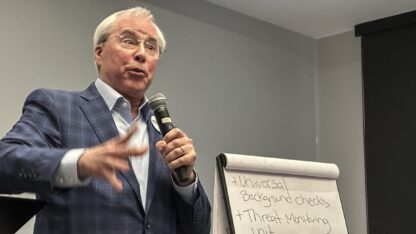

“The Supreme Court said a criminal statute needs to contain intent to disrupt and actual disruption,” Cannon told the Recorder at an event last week. “And the current statute does not have that. And in both of the cases, it’s important to remember that no one had intent to disrupt, and no one actually disrupted anything.”

In 2018, Williams, then a state senator, was arrested by Capitol police along with more than a dozen others as they protested ballot counting procedures in that year’s election in which Gov. Brian Kemp defeated Democrat Stacey Abrams by about 50,000 votes.

Prosecutors later dropped the charges, but Williams filed suit, arguing that the law used to arrest her was unconstitutional.

Cannon joined the suit after police used the same law to arrest her in 2021 after she knocked on the door of Kemp’s office where he was signing a controversial voting bill that Democrats opposed. Cannon’s attorneys said she was trying to find out when the bill would be signed. Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis ultimately declined to prosecute Cannon.

Attorney Gerald Weber said in Williams’ case, protesters were detained in the Capitol rotunda, which is traditionally a public forum where people come to hold signs and speak with lawmakers. The plaintiffs said the House and Senate were in session during the protest but were not disrupted.

Weber said the law is so broad that it could be used to arrest people demonstrating at Liberty Plaza, the public square near the state Capitol often used for protests, if police could construe the demonstrations as disrupting lawmakers informally meeting on the sidewalks outside the Capitol.

He said citizens coming to the Capitol to peacefully protest have been handed copies of the statute and had their speech silenced as a result.

“Here we have 16 persons arrested in two different events, all charges dismissed,” he said. “We have a whole host of other incidents, and we put affidavits in the record as to each of them, where people were silenced for signs, buttons, T-shirts, and even handed copies of this statute.”

Principal Deputy Solicitor General Ross Bergethon said the Capitol is not a public park but a workplace for hundreds of state employees.

“The state’s not obligated to open the Capitol at all,” he said. “The U .S. Capitol is not open in the same way, for instance, but it has. And I think we’d all agree that’s a good thing. The disruption statute simply reflects the nature of the building. It’s not about limiting anyone’s right to expression. People are still free to express any viewpoint they want, no matter how unpopular. It’s about making sure that the people working in the Capitol or attending a lawful assemblage there are free to engage in their own exchange of ideas or to perform their work without undue interference from others.”

In Cannon’s case, plaintiffs argued that her knocking on Kemp’s door was an expressive act protected by the state Constitution. Justice Charles Bethel questioned how knocking on the door violated the law.

“What does knocking on a door assigned to the governor’s office have to do with disrupting the General Assembly’s conduct?”

Bergethon said the government has a right to control offices in the Capitol.

“We’ve got to keep in mind that the rotunda is one thing,” he said. “That’s a designated public forum, and so the state can’t engage in viewpoint discrimination for the rotunda. The rest of the Capitol is offices, so the analysis would be no different from someone knocking on your chamber doors and disrupting you.”

The court is expected to decide on the case this year.

This story was provided by WABE content partner the Georgia Recorder.