A Georgia man and his family “have faced threats of violence and live in fear” since the movie “2000 Mules” falsely accused him of ballot fraud during the 2020 election, according to a federal lawsuit.

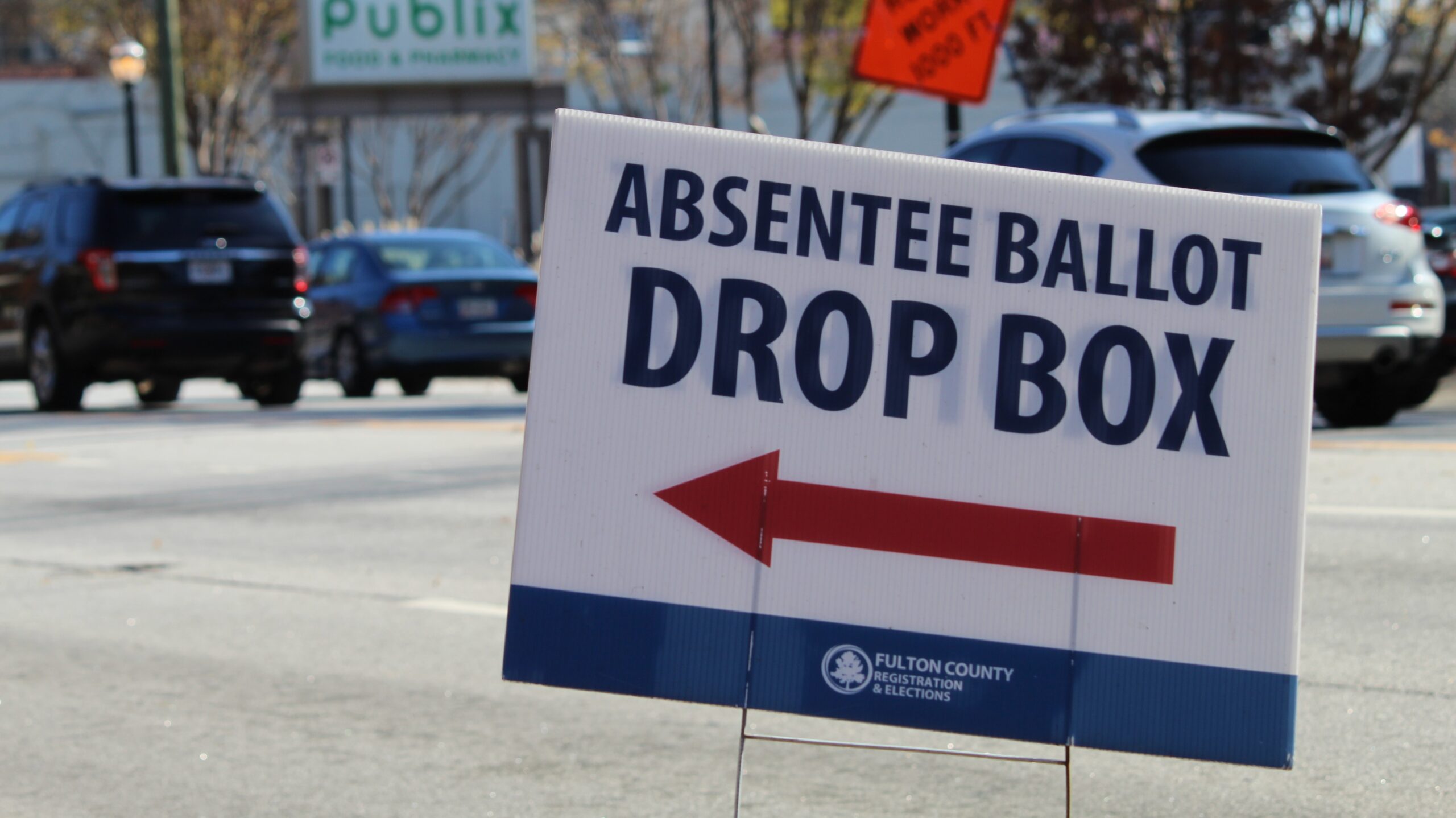

The widely debunked film includes surveillance video showing Mark Andrews, his face blurred, depositing five ballots in a dropbox in downtown Lawrenceville, a suburb northeast of Atlanta. A voiceover by conservative pundit and filmmaker Dinesh D’Souza says: “What you are seeing is a crime. These are fraudulent votes.”

In fact, a state investigation found, Andrews was dropping off ballots for himself, his wife and their three adult children, who all live at the same address. That is legal in Georgia and a state investigator said there was no evidence of wrongdoing by Andrews.

D’Souza’s film uses research from the Texas-based nonprofit True the Vote and suggests that ballot “mules” aligned with Democrats were paid to illegally collect and deliver ballots in Georgia and four other closely watched states. An Associated Press analysis found that it is based on faulty assumptions, anonymous accounts and improper analysis of cellphone location data.

State and federal officials have repeatedly confirmed that there is no evidence of widespread voter fraud during the 2020 election that could have changed the outcome of the presidential race.

The lawsuit names D’Souza and True the Vote, as well as the organization’s executive director Catherine Engelbrecht and Gregg Phillips, who has served on its board. Both Engelbrecht and Phillips appear throughout the film and served as executive producers and producers, the lawsuit says.

D’Souza did not immediately respond Friday to a request for comment submitted through his website. Engelbrecht and True the Vote have not responded to emails seeking comment, and contact information for Phillips could not be immediately located.

“At all times, Defendants knew that their portrayals of Mr. Andrews were lies, as was the entire narrative of 2000 Mules,” the lawsuit says. “But they have continued to peddle these lies in order to enrich themselves.”

Their social media accounts and website continue to promote the film using Andrews “as an example of a criminal ‘mule,’” the lawsuit says. While Andrews’ face was blurred in the film, video shown when the defendants were interviewed sometimes clearly showed his face and the license plate on his SUV, the lawsuit says.

The false accusations have caused distress for Andrews and his family, the lawsuit says.

“They feel intimidated to vote and have changed how they vote because of that fear,” it says. “They worry that again they will be baselessly accused of election crimes, and that believers in the ‘mules’ theory may recognize and seek reprisal against them, and that they may face physical harm.”

Andrews, who is Black, grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, before federal voting rights laws were passed and his “family taught him that his community and ancestors had fought, marched, and died for the right to vote,” the lawsuit says. Because of the “conspiracy to defame and intimidate him,” the suit says, “he will never again be able to vote without looking over his shoulder.”

Among other things, the lawsuit seeks an unspecified amount in damages and asks that false and defamatory statements about Andrews be removed from any website or social media accounts that the defendants control.