Jermaine Jones Jr. was riding with his uncle and father to get air for a tire the evening of Oct. 11, 2021, when officers from the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office pulled the Chevrolet Tahoe over because it had a tinted license plate cover.

The officers, who were staking out an apartment complex in Augusta for drug activity, ordered the men to sit on a curb as they searched the vehicle.

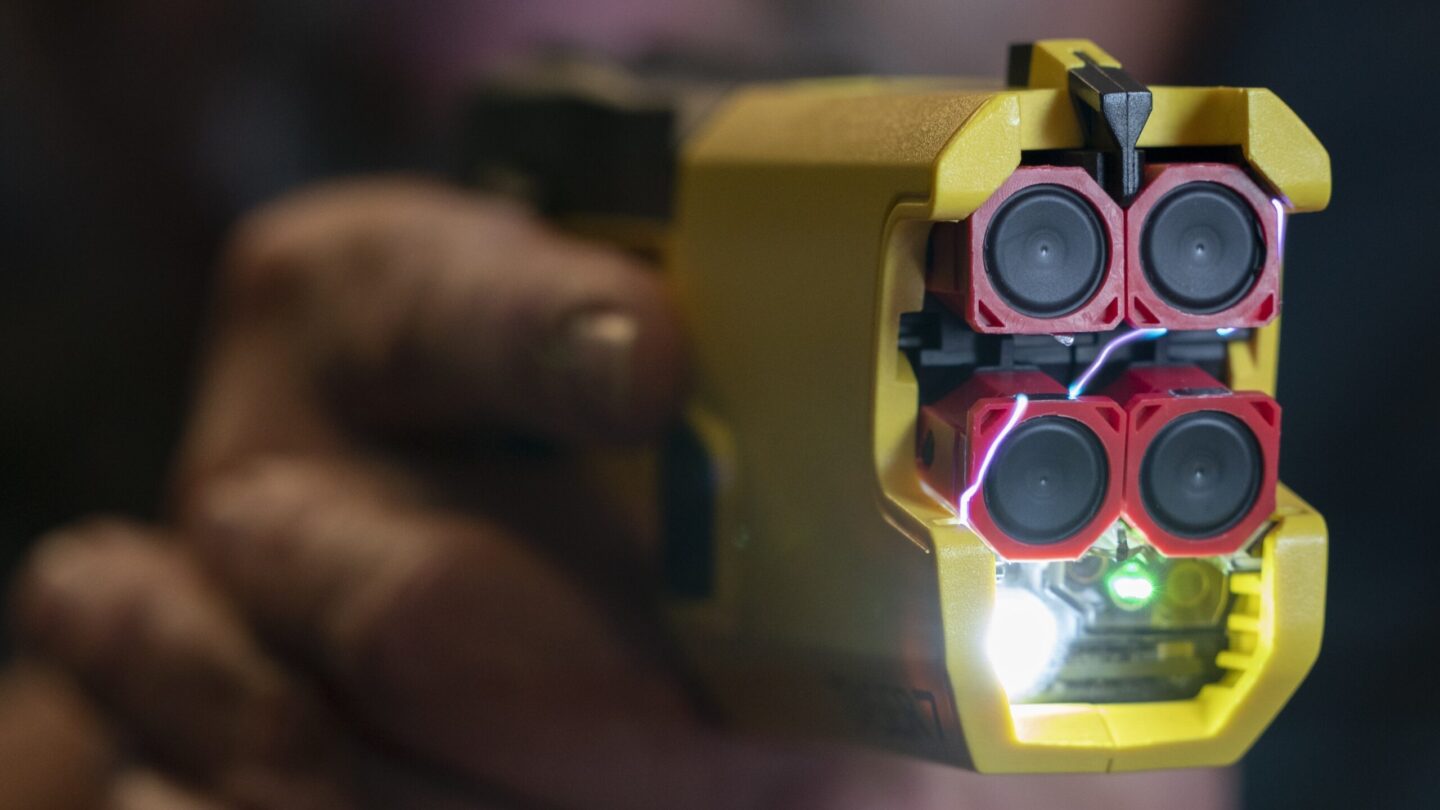

Jones ran as police found a gun inside the car, and Investigator Richard Russell immediately shot him with a stun gun. Jones’ body locked up from the jolt of electricity and he fell to the ground. Several officers tackled him, pinning Jones on his stomach and handcuffing him.

On the way to jail, Jones had a seizure and died a week later at Augusta University Medical Center. An autopsy described his death as a homicide from “delayed complications of blunt force head trauma due to ground level fall following shock from” the stun gun.

Jones was one of at least 30 people in Georgia who died during encounters with police that did not involve firearms from 2012 through 2021. In 20 of those cases, officers used stun guns. In nine of those 20 encounters, men were both shocked with the stun gun’s sharp projectile prongs, which temporarily incapacitate a person, and “drive-stunned” when the weapon was triggered against their skin or clothing to elicit compliance through pain.

The Georgia Legislature passed statewide stun-gun training requirements in 2006, but has never funded them. The weapons are used as an alternative to firearms — a kind of “less-lethal force” that the manufacturer of Tasers warns can be risky under certain circumstances, such as when someone could fall or when a person is obese or has pre-existing health problems.

The Associated Press spent three years identifying cases across the country where encounters involving less-lethal force turned deadly. Working in collaboration with AP, reporters for the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland zeroed in on Georgia — with its blend of urban and rural communities, and relatively good access to government records — to understand how those deaths occurred.

The Richmond County Sheriff’s Office and the DeKalb County Police Department had the most non-shooting deaths among Georgia agencies during the decade the investigation covered. Of the three people who died after encounters with Richmond deputies, stun guns were used in two cases.

The sheriff’s office requires deputies to complete up to eight hours of stun-gun training, said Lt. Michael D. Humphreys, the agency’s lead use-of-force instructor. A review of the deaths in Richmond County where stun guns were used shows that officers didn’t always follow best practices in the field.

In 2013, a Richmond County deputy fired a Taser to try to stop George Harvey from walking toward a busy highway. During a struggle that followed, the deputy said he shocked Harvey again multiple times in the back. A Taser log shows he fired five times for 29 seconds in all.

Deputies used handcuffs and leg restraints to control Harvey in addition to holding him facedown. A medical examiner ruled Harvey’s death a homicide, although the cause was attributed not to the force but to a combination of cocaine, methamphetamine and ethanol toxicity.

Two years before Harvey’s death, in 2011, the Police Executive Research Forum, a national law enforcement policy group, and the Justice Department issued guidelines saying officers should be taught that multiple uses of a stun gun may increase the risk of death. The guidelines recommended capping the electricity at 15 seconds — typically three stun gun blasts of five seconds each.

By 2013, Axon, the manufacturer of Tasers, warned in its training manual to “avoid prolonged and repeated exposures” and cited concerns from law enforcement and medical groups about going beyond 15 seconds.

Richmond County training staff said their aim is to equip officers with options to choose from in complex and rapidly changing situations. Patrick Clayton, former chief deputy in the sheriff’s office, said stun guns give officers an alternative to going “hands on” with people who resist arrest. “What we found is that it reduces injuries to the defendants and it reduces the injuries to the officers as well,” Clayton said.

Capt. Glenn Rahn, who oversees professional standards and training at the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office, said staff are training deputies to avoid using stun guns when the offense is minor.

Jermaine Jones’ mother, Keyana Gaines, is still looking for closure after her son’s death.

The 2011 national guidelines said “fleeing should not be the sole justification” for firing a stun gun. Russell, who fired the stun gun at Jones, resigned from the Richmond County force on Feb. 4, 2022, his personnel records show. Now an officer at the Thomson Police Department outside Augusta, he declined to talk about the encounter when reached in February.

A criminal investigation into Jones’ death closed at the end of 2022 when the district attorney decided not to prosecute any of the officers. Gaines filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the sheriff and four deputies in October 2023.

In spite of Richmond County’s stun-gun training, people continued to die after Jones’ death.

Christopher Blount died in October 2022 after Richmond County officers found him hiding in a bathroom in an Augusta home, where he had been drinking and acting erratically. Blount ran into a bedroom closet, throwing metal rods at deputies, before they shot him with a stun gun, turned him on his stomach and drive-stunned him. He became unresponsive and died on the scene.

That December, Nelson Lee Graham Jr. died at the hospital after he failed to give Richmond County deputies his arms to be handcuffed and deputies shot him with a stun gun and drive-stunned him in his bedroom. Graham’s wife had called a mobile crisis hotline for help getting her husband a court-ordered mental evaluation.

The 2011 national guidelines warned of the potential for serious harm or death when stun guns were used on people “in medical/mental crisis, and persons under the influence of drugs (prescription and illegal) or alcohol.”

The Richmond County Coroner’s Office classified both deaths as homicides. Blount’s was caused by “cardiac arrhythmia associated with cocaine toxicity and physical restraint.” Graham’s death was caused by “physical altercation involving prone positioning, mechanical asphyxia, and electroconductive device use in the setting of schizoaffective disorder.”

The Richmond County Sheriff’s Office declined to talk about the deaths, citing pending litigation. The District Attorney’s Office also declined to comment.

In February 2023, the department spent more than $207,000 on new Tasers for its officers, records show.

“They traded guns for Tasers,” Gaines said in an interview with Howard Center reporters. “Now all of a sudden, the more tasing going on, the more people are dying.”

Torrence Banks, Winter Hawk, Abbi Ross, Paige Maizes, Aiesha Solomon, Nyrene Monforte and Evan Hecht also contributed to this story. All reported for the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism in the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland.