First-time poll worker Kirubel Behailu thought he’d become more familiar with Georgia’s new voting machines at a quiet election site during Tuesday’s primary.

Instead, he found himself scrambling to sanitize equipment, clear jams in a ballot scanner and run back voter cards during a 15-hour marathon at an Atlanta church inundated with frustrated citizens.

“I broke a sweat throughout the day. I logged at least 10,000 steps. It was kind of overwhelming,” said Behailu, one of several poll workers who shared their experiences with The Associated Press.

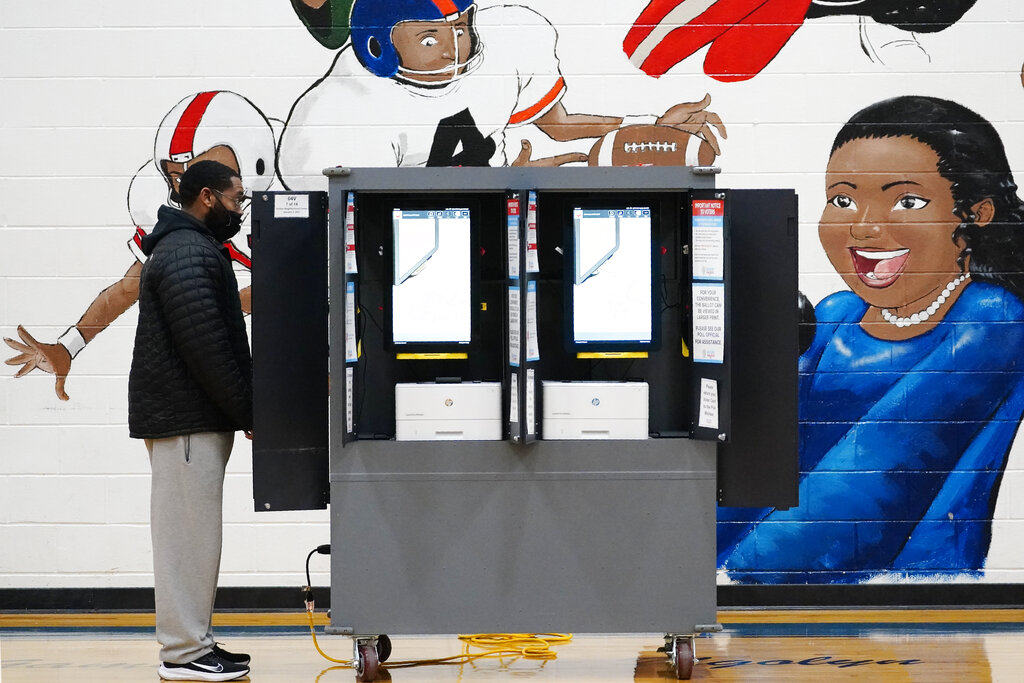

Voting problems were reported across much of Georgia, forcing 20 of a 159 counties to extend voting in at least one precinct. But it was particularly messy in metro Atlanta.

Election officials in Fulton County — the state’s most populous — faced a backlog of thousands of absentee ballot applications after staff became sick with the coronavirus and a deluge of requests froze email accounts and jammed printers.

Many voters who didn’t get their absentee ballots had to crowd into polling sites that had been consolidated because of the virus. Lines then grew because social-distancing requirements limited the number of machines that could be used in confined spaces.

Voters at Behailu’s site reported waiting up to two hours; some voters elsewhere said they had to wait up to five hours; others simply gave up.

Voting hours were extended at every Fulton County polling site, with the last ballots cast around midnight.

Georgia’s top elections official, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, had expressed confidence for months about his rollout of the new machines, despite warnings by voting rights advocates that poll workers wouldn’t have enough time to learn how to use them.

Then the pandemic happened, limiting in-person training, even as many experienced poll workers were scared off over fears of getting sick.

Kaelen Thomas, 21, who staffed another polling site in Atlanta, said he didn’t think the training they were given on the new voting equipment was sufficient for older workers who may not have as much experience with technology. Still, he pushed back on any criticism of the workers.

“I think it comes down to poor planning first and foremost,” he said.

For some workers, the day was harrowing.

Behailu, 25, said the troubles at his polling site near Piedmont Park started early, with workers “running around in circles” before the polls opened to power up a battery pack that supports the voting equipment. The first people to vote received error messages when they inserted electronic cards used to bring up their ballot. And at some point it started raining, and workers raced to restructure the line so more people would fit inside while staying 6 feet apart.

“I was walking in there pretty blind,” he said. “I had no idea what to expect.”

Officials struggled to recruit workers amid the pandemic. Behailu, who expected to be paid $15 an hour for his work, said he was pulled between tasks and thought his location could have used at least two or three more workers.

“Imagine your feeling when you’re at 6 p.m. on a 13-hour shift, and then they add three more hours,” said Evan Malbrough, who also staffed a polling location in Atlanta on Tuesday. “I’m not advocating for closing polls early or voter suppression, but I think that needs to be put in the conversation because it’s not just voters at the polling location.”

Malbrough recruited 86 young poll workers, including Behailu, through his work with a voter advocacy organization run by students. Now he worries many won’t come back to help in November.

“You have to have tough skin to be a poll worker because there’s a lot of angry people and rightfully so,” Malbrough said.

The coronavirus was also a source of anxiety.

Jazmin Mejia, 22, staffed a polling location in South Fulton, Georgia during early voting. She said people had trouble understanding what workers were saying with their masks on, so they would try to “peer over” a protective screen on a table to hear better.

“It was kind of like, ‘You’re missing the point of the screen,’” she said.

Voter Alynn Gordon, a 31-year-old research analyst, abandoned two attempts to cast her ballot in Atlanta because of long lines before emerging triumphant around 9:45 p.m. Tuesday, among the last people to vote at her site. She said a poll worker didn’t provide clear direction about how to feed her ballot into a scanner, but they seemed to be doing their best.

“I don’t know maybe that they were smiling at that point in the day,” she said. “But I wouldn’t expect them to be bright and cheery at that hour.”