Anthony Pacheco is Latino, but for the last several years he has worked as a community organizer at the nonprofit Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta.

More than once, people have asked him why.

“I see a lot of parallels between Latinx communities and Asian American communities here in Gwinnett County,” Pacheco says, in a conference room just off the main hall of the public library, where the shelves are lined with books in Spanish, Vietnamese, Korean and Mandarin.

Pacheco says Gwinnett County is a place where many cultures mesh. “Where I get my haircut, it’s a Vietnamese place,” he says.

This week, about 20 miles southwest at the federal courthouse in Atlanta, a judge is considering whether the federal Voting Rights Act protects communities like this one — so-called “coalition districts” where together, Black, Latino and Asian American voters form a majority.

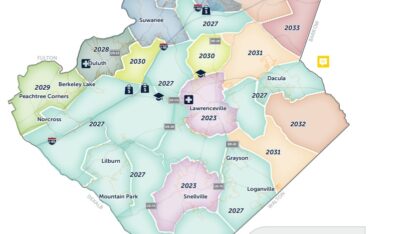

The fight over Georgia’s political maps has already had several steps. After the judge in October found the maps illegally diluted the power of Black voters, Republican lawmakers were forced to revise the district lines to add new, majority-Black districts.

But the Republican majority preserved its overall partisan advantage in U.S. House seats by dismantling the congressional district covering most of Gwinnett County, prompting outcry from plaintiffs and Democrats.

Last year in that district, a coalition of Black, Latino and Asian American voters helped elect a Black Democrat, Lucy McBath, to Congress.

Pacheco says many Asian American and Latino voters here share common policy interests like immigration reform and access to language services.

“I remember growing up, first generation American, and I’m 8, 9 years old, helping my mom translate her bills, setting up doctor’s appointments,” Pacheco says.

“I went through a similar experience,” says James Woo, a colleague at Asian Americans Advancing Justice. “I came here when I was 10, but my parents came when I was in college. Their language was always limited, so I had to be the manager of the beauty supply store.”

Are “minority opportunity” districts protected?

When U.S. District Judge Steve Jones ordered Georgia lawmakers to add new majority-Black districts, he also warned them against dismantling “minority opportunity” districts elsewhere.

Republicans and Democrats disagree about what the judge meant.

“The only minority they were talking about in this case was Black voters. That was it,” said state Rep. Rob Leverett, one of the chairs of Georgia’s Republican-controlled redistricting process.

“This notion that we’re throwing plans up here that cavalierly don’t comply with the order is just particularly offensive,” Leverett said before the maps passed along party lines during a special session this month.

“The fact that the General Assembly added the required majority-Black districts while not substantially increasing Democratic performance is apparently why Plaintiffs object to the plans,” the state wrote in a brief.

Democrats, and the civil and religious groups who first sued over Georgia’s maps, say the revised districts violate the judge’s order and are asking for an independent, special master to draw the maps, like in Alabama.

“The General Assembly’s purported remedy makes a mockery of that process, the court’s ruling, and the Voting Rights Act, and reflects the state’s continued refusal to afford minority voters equal opportunity to participate in the electoral process,” the plaintiffs’ attorneys wrote.

One way Democrats say Republicans have done that is by eliminating some districts where multiple minority groups — not just one — comprise a majority.

But federal appeals courts have split on whether the Voting Rights Act even protects “coalition districts.”

For example the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which includes Georgia, has previously found that the act protects coalition districts. But the 6th Circuit has ruled the other way, and the 5th Circuit agreed to take up the issue next year in a case about local maps in Galveston, Texas.

The U.S. Supreme Court has not weighed in — yet.

“A moment of change”

“I think we’re in a moment of change for the Voting Rights Act and for race in American politics,” says professor Michael Kang, an expert in election law at Northwestern University School of Law.

Kang says conservatives see a chance to narrow the Voting Rights Act by bringing cases that could reach the conservative U.S. Supreme Court. Georgia is one of several states, for example, challenging the ability of private individuals and groups to bring challenges under one key section of the law.

This renewed push to weaken the Voting Rights Act, Kang says, comes just as the country’s growing diversity demands a more expansive interpretation of the landmark legislation.

As suburban communities like Gwinnett County desegregated in recent decades, Kang says fewer places are majority-Black or majority-Latino.

“We’re seeing an increasingly multiracial democracy that the voting rights law that we have wasn’t built to handle very well,” Kang says. “It can be adapted, I think, but will depend on what judges do with the precedent and the Voting Rights Act. I’m not really sure what’s going to happen.”

Politically cohesive?

At Plaza Las Americas, a former big box hardware store turned Latin American shopping mall in nearby Lilburn, vendors sell everything from quinceanera dresses to auto supplies, pet birds and cosmetics.

Before ordering a coffee and arepas at the food court, Brenda Lopez Romero, chair of the Gwinnett County Democrats, says the law must protect these increasingly multiracial communities, too.

Lopez Romero says Black, Latino and Asian Americans voting together is what makes Gwinnett County a Democratic stronghold.

But recently, the GOP has invested in peeling away some Latino and Asian American voters. That could make it harder for the courts to see these groups as “politically cohesive,” potentially threatening their protections as a coalition under the Voting Rights Act.

Lopez Romero says movement away from Democrats is overhyped.

“It’s quite frankly not significant,” she says. “The part about coalitions being of similar interest is not the same as asking us to be the same.”

Attracting new voters is a necessity for Republicans, as Georgia’s white population shrinks. But Ray Harvin, with the Democratic Party of Georgia’s Gwinnett County African American Caucus, says Republicans are also wielding redistricting to preserve their majorities as the state becomes more politically competitive.

“Georgia is in the game,” Harvin says. “And in the future, as this coalition of voters grows, we’re going to have this fight over and over again.”

The outcome over political districts may shape not only which party controls the next Congress, but also, the future of the Voting Rights Act itself.

Meanwhile, time is running out for the courts to finalize district lines in Georgia, where election officials have to prepare ballots for primary elections in the spring.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))