When a conservative organization announced plans this month to launch an election integrity operation in Georgia, the group’s news release included a high-profile name: the chairman of the state’s Republican Party. Less than a week later, the same group announced plans to challenge the eligibility of hundreds of thousands of Georgia voters.

To Democrats in the state and voting rights advocates, it was verification of what they have long argued — that the Georgia GOP is supporting efforts to suppress voting in one of the nation’s newest political battlegrounds. It also raised questions about the legality of any coordination between the state party and the group True the Vote, charges the organization’s founder disputes.

A relatively obscure conservative group, True the Vote is among the numerous political organizations descending on Georgia ahead of a pair of high-stakes Senate run-offs on Jan. 5. The outcome of the contests will determine which party controls the Senate as President-elect Joe Biden launches his administration.

On Dec. 14, True the Vote announced it was launching an “election integrity” campaign in Georgia as “partners with (the) Georgia GOP to ensure transparent, secure ballot effort” for the Senate runoffs. The release featured a quote attributed to Georgia Republican Chairman David Shafer: “The resources of True the Vote will help us organize and implement the most comprehensive ballot security initiative in Georgia history.”

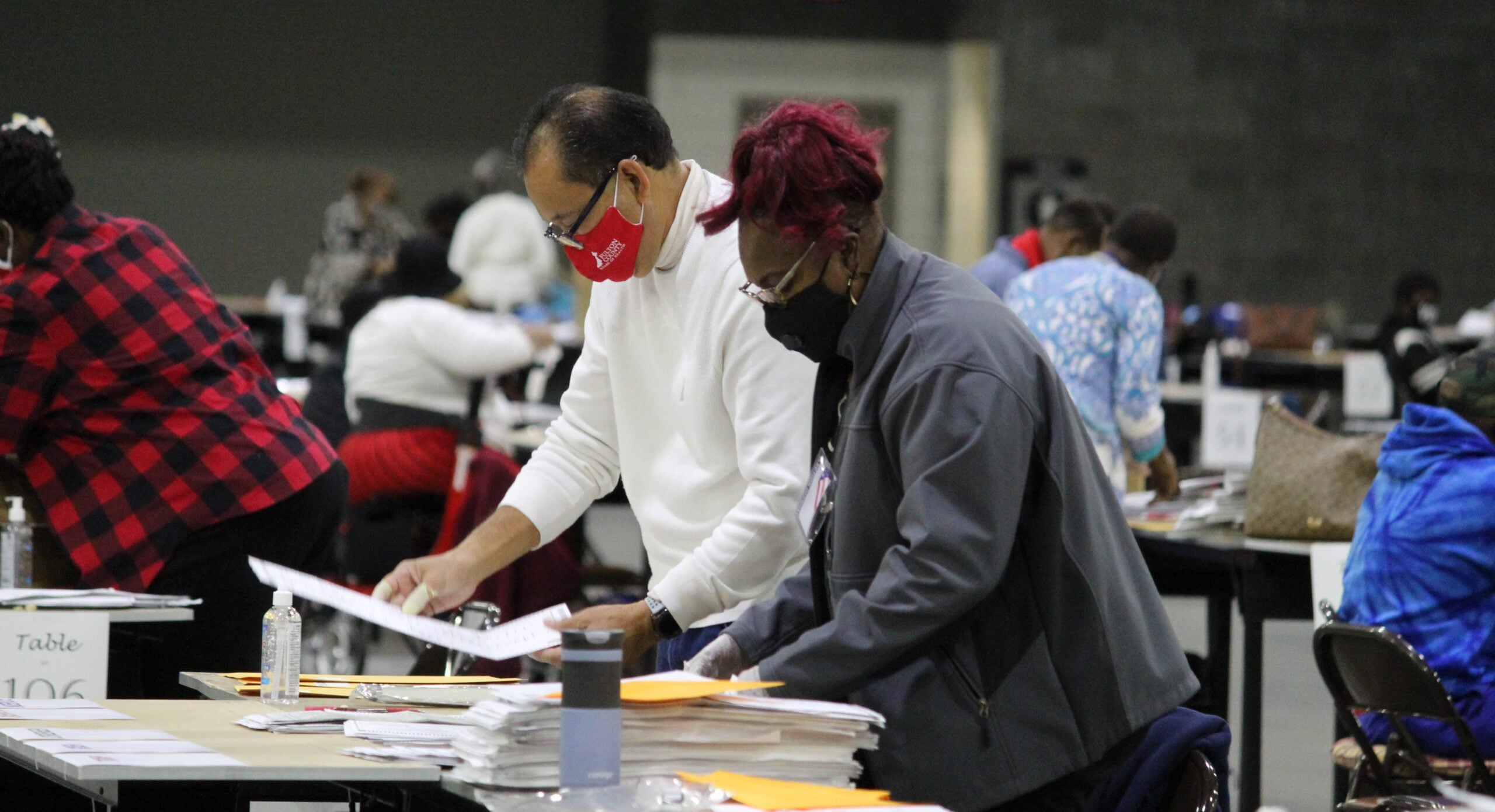

The Dec. 14 release described True the Vote’s effort as “publicly available signature verification training, a statewide voter hotline, monitoring absentee ballot drop boxes and other election integrity initiatives.” Days later, the group said it was challenging the eligibility of more than 360,000 voters spread across all 159 Georgia counties. The state GOP was not featured in that disclosure.

Campaign finance law forbids political parties from accepting contributions — including non-cash, “in-kind” contributions of goods and services — from any corporation. Not-for-profits with the tax status granted to True the Vote also have strict limits on the kind of activities they conduct, essentially allowing for generic voter registration and turnout drives.

Adav Noti, an elections law and campaign finance law expert at the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center in Washington, said the law means True the Vote “absolutely cannot collaborate with a political party on voter registration or get-out-the-vote efforts or anything related to those areas in a campaign.”

True the Vote founder Christine Engelbrecht, a former Texas tea party leader, disputes that, saying there is no “coordination” with Shafer or any of his staff. She said training materials her group is providing for poll workers, for example, are publicly available and the state GOP is not involved in any training sessions with True the Vote. She acknowledged, though, that some poll workers who get True the Vote materials could end up volunteering for the GOP as poll workers.

Georgia Republican Party officials, including Shafer, did not respond to multiple inquiries from The Associated Press about the party’s relationship with Engelbrecht.

True the Vote was founded in 2009 and has a reputation for training conservative poll watchers to be aggressive in highlighting potential voter fraud. Voter fraud in the United States is rare, and there is no evidence of any significant problems in this year’s presidential election. That has been confirmed in Georgia by Gov. Brian Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, both Republicans, and nationwide by officials including Attorney General William Barr.

But much of Engelbrecht’s work in the weeks before the Georgia runoffs is focused on identifying registered voters her group argues are not eligible. She said her group’s citizen-led challenges to tens of thousands of Georgia voters are based on residency records.

Lauren Groh-Wargo of Fair Fight Action, a political organization started by Georgia Democrat Stacey Abrams after she lost the 2018 governor’s race, called it “a Hail Mary attempt by Republicans to suppress the vote two weeks out from an election, with people already voting.”

Early voting in Georgia began Dec. 14, the same day True the Vote said it had formed an alliance with the state Republican Party. Both parties expect close races between Republican Sens. David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler and their respective Democratic challengers, Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, reflecting Georgia’s new status as a battleground state. Biden became the first Democrat to carry Georgia in a presidential race since 1992, edging President Donald Trump by just 12,000 votes out of about 5 million cast.

Elections officials nationwide routinely conduct maintenance of voter rolls — removing voters who have moved or died or have been inactive for certain periods of time — between election seasons. But federal law prevents those practices so close to an election. True the Vote, however, is taking advantage of a state law that allows individual voters to challenge another voter’s eligibility. A state court in Fulton County, which includes most of the city of Atlanta, ruled earlier this year that federal restrictions on changing voter rolls within 90 days of an election overrides state law. That ruling, however, doesn’t necessarily apply statewide.

In at least one populous Georgia county — suburban Atlanta’s Cobb — the local elections board already has rejected True the Vote’s challenges. But in Muscogee County, home to Georgia’s second-largest city, Columbus, the board found “probable cause” for the complaints. That means the affected Muscogee voters — Groh-Wargo said they number several thousand — could have to cast provisional ballots and then prove their eligibility to have those ballots counted.

Engelbrecht said her group has filed challenges in as many as 85 counties.

She insisted the voter challenges are separate from True the Vote operations that might overlap with the GOP’s election-security program. She said neither Shafer nor any of his subordinates played any role in corralling the Georgia voters who filed the challenges with local elections officials.

She added that no money has changed hands between the party and True the Vote.

Noti, the elections law expert, said federal law is clear that “a contract or an agreement or an exchange of money is not required for coordination to be established.”

It’s not the first time that Engelbrecht’s activities have drawn scrutiny. She spent years fighting with the IRS to win her group’s tax-exempt classification. And most recently, True the Vote declared itself aligned with Trump’s reelection campaign and its multistate legal effort to overturn the general election results. That drew considerable financial support, including top Trump donor Fred Eshelman, according to Bloomberg News.

But after True the Vote ended several of its lawsuits in battleground states, including Georgia, Eshelman filed suit against Engelbrecht’s organization to recover a $2.5 million contribution, alleging it had failed to investigate and expose any election fraud.