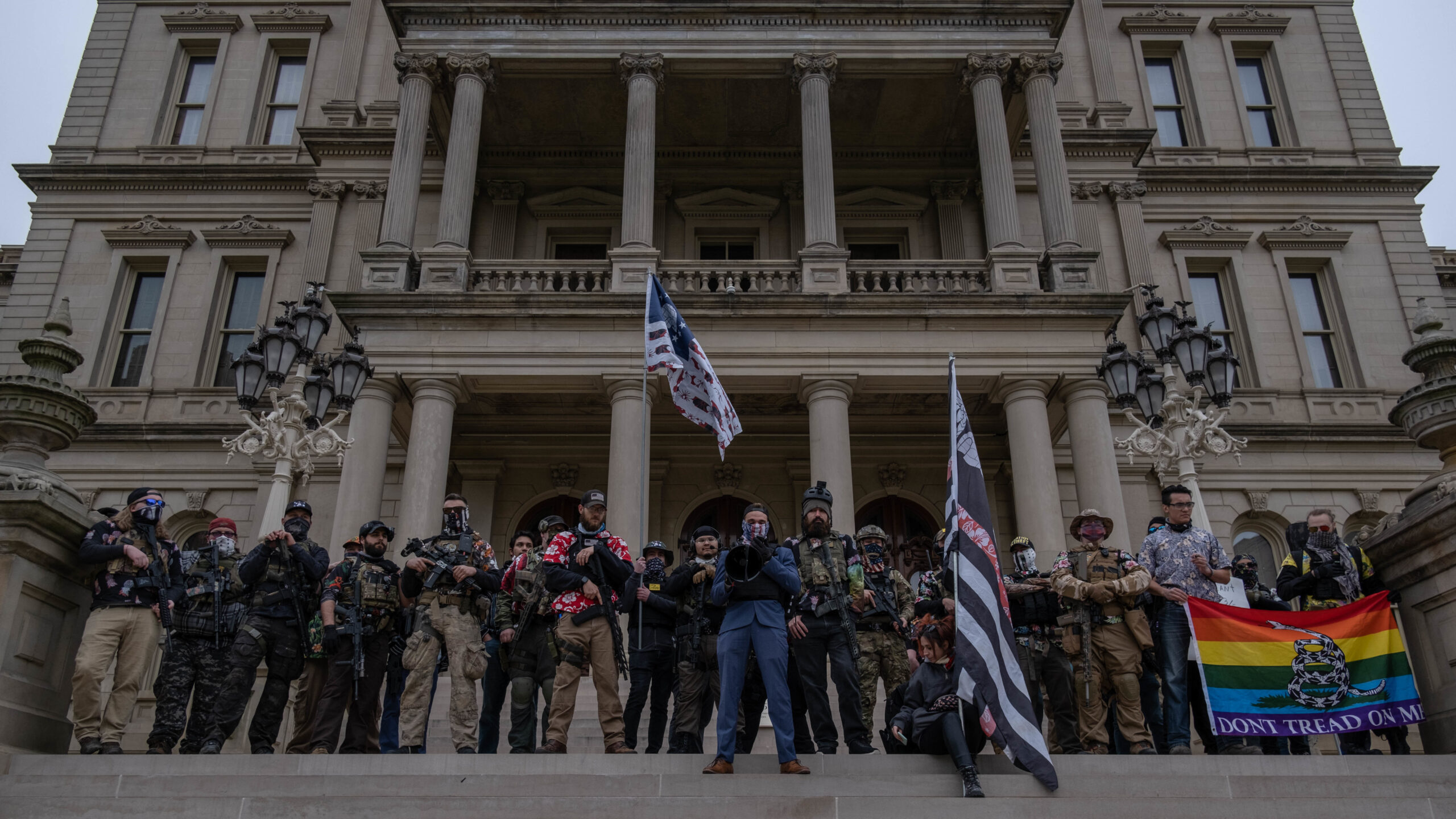

Five states — Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Oregon — have the highest risk of seeing increased militia activity around the elections: everything from demonstrations to violence.

That’s the conclusion of a new report by ACLED, a crisis-mapping project, and the research group MilitiaWatch. They worked together to map out potential hot spots for militia-style activities around the elections.

Their report looks at states where militias have had recruitment drives and training, where they have cultivated relationships with law enforcement and where there has been substantial engagement in anti-coronavirus-lockdown protests.

Those factors are local indicators of whether militia activity might occur. For example, cultivating relationships with police suggests that law enforcement might view the militia groups as helpful, rather than a threat. And anti-coronavirus-lockdown protests are linked to militia activity because many of those groups believe that the state doesn’t have the authority to impose such restrictions.

The report comes out as the risk of political violence around Election Day by vigilantes or militia-style groups is increasing, researchers say. Far-right, militia-style groups have been busy this year: Their numbers are growing, their online chatter is increasing and their threats are becoming more specific.

“In the conversations that I observe, the heat is higher. The vitriol is greater,” said Megan Squire, a computer science professor at Elon University who studies right-wing extremism and online spaces.

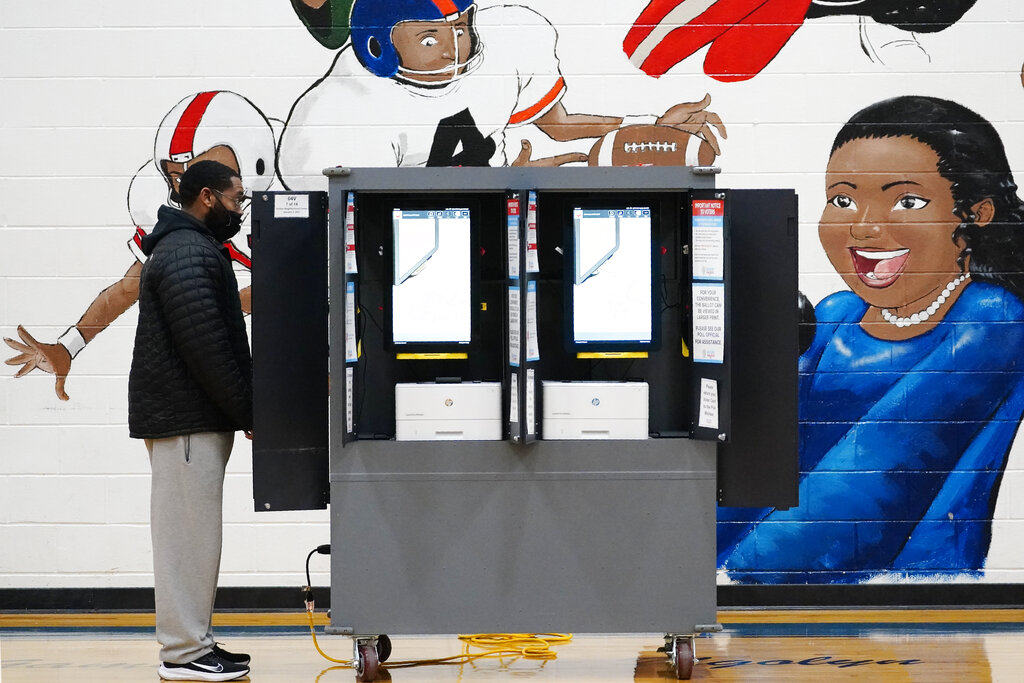

The range of real-world militia activities that could occur include everything from armed demonstrations to voter intimidation to violence. The rhetoric is heated, in part, because a mosaic of groups on the far right with different goals agree on one thing: that President Trump can lose the election only if it’s rigged.

“There’s circulation of rumors of left-wing intervention at the polls or in the election, which has led to individuals and militia groups discussing primarily showing up armed at the polls, like to see if there’s anything suspicious or what they deem suspicious,” said Hampton Stall, the founder of MilitiaWatch, which tracks the right-wing militia movement.

The commentary and planning are getting harder to track online. Facebook and Twitter have cracked down on militia-style groups, but such groups have moved the conversation to other places. Those places include social media networks that are more permissive with the groups’ content and discussion boards where militia members can meet and organize.

“It becomes a lot harder for people like me and my colleagues to track them, because we watch them kind of splinter into other places,” said Cassie Miller, a senior research analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The threats by militia-style groups have been growing in number, vitriol and specificity — culminating in things like the alleged plot by six men in Michigan to kidnap that state’s governor, Gretchen Whitmer.

“There’s a lot more worst-case-scenario thinking that is leading to fantasizing about violence and very real militarized action that hasn’t really been as widespread in the militia movement as it is now,” said Stall.

A patchwork of federal and state laws against voter intimidation exists to protect the process.

And voting rights activists say they worry that the attention generated by the militias could depress voter turnout. They say that even if there is an increased risk of militia activity, it is important to keep it in perspective.

The risk, says Gerry Hebert of the Campaign Legal Center, is that people may be afraid to go to the polls if there is too much hype around militia rhetoric.

“It is designed to maybe keep people from showing up because they fear that there might be some activity, when, in fact, it’s just a chilling commentary,” he told NPR.

All of this adds to the tensions in an already deeply contested and divisive election season.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))