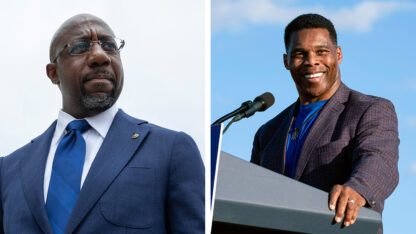

Republican Herschel Walker has plenty to say about how his Democratic rival, U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock, does his job in Washington. But Walker is considerably less revealing about what he’d do with the role himself.

A former football star and friend of former President Donald Trump, Walker tells voters he supports agriculture, veterans and law enforcement. He sells cultural conservatism and his mental health advocacy. He tags Warnock as a yes-man for President Joe Biden. Yet when asked for concrete alternatives to “the Biden-Warnock agenda,” Walker defaults mostly to generalities and stem-winding tangents — or he turns the question around.

“Have you asked my opponent? Don’t play games. You’re playing games,” Walker told reporters recently when pressed to clarify his stance on exceptions to abortion bans.

The broader approach tracks the way many political challengers — including Warnock two years ago — try to put incumbents on the defensive.

That method is especially salient for Republican candidates in a midterm election year when Democrats must run alongside sustained inflation. But Walker’s rendition, as much as any GOP candidacy nationwide, is testing the bounds of that strategy as Democrats hammer the political novice as unfit for high office.

“There is a stark difference between me and my opponent,” Warnock said at a recent campaign stop, theatrically stretching the word “stark” as he smiled. “This race,” the senator continued, “is about who’s ready to represent Georgia.”

Democrats’ paid advertising levels the same charge, without humor.

Among Warnock’s first general election ads was video of Walker claiming he knows of a cure for COVID-19. “I have something that can bring you into a building that would clean you from COVID as you walk through this dry mist,” Walker said. “This here product — they don’t want to talk about that.”

Another Warnock ad hammered Walker for not agreeing to any of three long-standing Georgia general election debates after saying he’d debate Warnock “any time, any day.”

Other ads from Warnock-aligned groups have chronicled Walker’s exaggerations about his business and academic accomplishments and his first wife’s allegations of Walker’s violent behavior.

Those spots are part of an advertising deluge that’s allowed Warnock to burnish his personal brand, explain his Senate record on his terms and launch broadsides against Walker. That reach could prove decisive in a closely divided state: Warnock won his January 2021 special election runoff by 2 percentage points out of 4.5 million votes. Polls suggest reflect another hotly contested race, with Republicans depending on Walker to tilt the balance of the 50-50 Senate.

Warnock has fueled his ad blitz with a considerable money advantage. From the closing weeks of 2020 through June 30 of this year, he’d spent more than $85 million. Walker, by comparison, had raised $20.2 million and spent $13.4 million.

That leaves some Republicans fretting that Walker is behind in establishing his case. “I get really passionate about this because I know Herschel, and the left is trying to paint him into something he is not,” said Ginger Howard, a Georgia representative on the Republican National Committee.

Walker’s answer so far is to make the race a referendum on Biden and Democrats, thus avoiding direct comparisons between the Georgia nominees.

Walker aides say that isn’t just the obvious course to navigate a first-time candidate’s liabilities; it also happens, they insist, to resonate with a majority of Georgians.

“This is still a center-right state in a very Republican year,” said adviser Chip Lake, noting Biden’s approval ratings lag badly behind Warnock’s standing in Georgia. “Voters aren’t asking Herschel for white papers on policy.”

Liz Marchionni, who volunteers at her local Cobb County Republican office north of Atlanta, said most voters care more about broader values than specifics. “Every candidate should answer questions,” she said. But Walker “has excellent business experience,” she added. “He’s a strong Christian. And he’s working for freedom for all Americans.”

Nonetheless, the first-time candidate has started doing more policy-themed events: roundtables with farmers, meetings with business owners, gatherings with law enforcement, a panel with conservative women, including the candidate’s wife, Julie Blanchard. Walker now huddles regularly with groups of reporters.

Much of that is a shift from his shielded Republican primary campaign. He easily won that contest anyway, leveraging his fame as a former University of Georgia football star and his relationship with Trump. But Lake said the campaign recognized Walker has to “engage with as many Georgians as possible” to defeat Warnock.

In recent appearances, Walker has talked of prioritizing aid to farmers, cutting environmental regulations he says limit domestic energy sources, and championing “second chance” policies to help convicted felons get employment.

But he doesn’t get into details, and his go-to applause lines reflect standard conservative dogma. “We need spiritual warriors … leaders who love this country … people with common sense,” he told a standing-room-only crowd in northern Cobb County.

Lake said “it’s no different than any other campaign I’ve worked on.” And, he added, “I don’t remember Raphael Warnock’s campaign being that detailed” ahead of his victory over then-Sen. Kelly Loeffler.

Indeed, Warnock’s standard pitch this summer is more policy-heavy than in 2020, in part because he talks about measures that he’s helped get through the Senate. Yet in that campaign, Warnock did tout his activism as a Baptist pastor on Medicaid expansion and voting rights, holding forth on policy details. For example, he talked then about capping insulin costs and allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical firms. The Senate recently approved drug-price negotiations and a limited version of the insulin cap. Republicans restricted the cap only to Medicare; Warnock called for extending it across all consumers, including the privately insured.

Walker’s latest forays into policy highlight the potential risks in trying to match Warnock.

Discussing inflation before the recent Senate votes, Walker said he endorsed capping insulin prices. Told of Warnock’s efforts, he replied: “I support some of the good things he’s doing, but that’s just a Band-Aid. Why don’t he get back and get to things that are correct?”

Walker didn’t answer a follow-up question about what policies he’d pursue to combat the wider inflation he blames on Warnock. Instead, he veered into a soliloquy on border patrols and crime.

After accusing Warnock of supporting the Inflation Reduction Act without “reading the bill,” Walker admitted he’d read only “some of the bill” himself.

Meeting with north Georgia farmers, he learned that a majority of the federal farm bill — a staple of federal spending for generations — finances consumer food assistance. Farmers don’t necessarily oppose that consumer aid, though Congress often fights over amounts. But Walker heard the breakdown and mused that it is wasteful, even as one farmer explained that feeding a country of 330 million residents “is national security.”

Walker glosses over details when attacking Warnock, as well. Talking about why women should support him, Walker said, “I will keep them safe, not like my opponent, who votes to be soft on crime and soft-on-crime judges.” Walker then alluded to an unspecified local prosecution in Atlanta, alleging it involved defendants who’d been arrested more than 100 times.

“These guys have done so many crimes, and they let them out of jail,” he said. “Right now, that’s something that I would be tough on right there.”

Asked recently which Senate committee assignments he’d seek should he win, Walker said he wants to focus on agriculture and “something with our military” and supporting veterans.

Follow AP for full coverage of the midterms at https://apnews.com/hub/2022-midterm-elections and on Twitter, https://twitter.com/ap_politics.