For nearly half a century, Sweet Auburn served as the blueprint for entrepreneurship, generational wealth and activism among Atlanta’s African American community. Now, longtime residents are hopeful that with renewed interest from businesses and city government, the prosperity of the neighborhood’s past can be repeated despite the struggles of the present.

Janis Perkins, owner of the Odd Fellows Building, has been active in the community since 1956 after relocating from Nashville. She said she’ll never forget her first time walking through the area.

This Year on WABE: 2023

2023 was a big year at WABE. We turned 75, launched WABE Studios, and the WABE Newsroom continued to cover the critical issues Atlantans care about most. Here are a handful of stories, photos, television and podcasts we think stand out from this year.

“To see all the businesses that were here and owned by Black people, I guess you didn’t think about it at the time, but… I was surprised. It was something that I was not used to seeing from being in Nashville. It was great seeing that type of movement all throughout Auburn.”

It’s because of residents like Perkins’ commitment to preserving history that the sweetness that made up Auburn in its heyday continues.

The Odd Fellows Building, while extensively renovated by Perkins and her late husband Robert in 1987, was the largest construction project in the United States at the time to be supervised and funded entirely by Black men. It originally opened in 1912, with Booker T. Washington in attendance.

An adjacent auditorium was opened to the public the next year and grew to become a go-to spot for African American talent throughout the 1920s and 1930s, with artists such as Cab Calloway and Lionel Hampton appearing in later years.

“It was the only place for our people to entertain,” said Perkins, who proudly points out the original floor plan of the auditorium, still in existence at the building. “They could not perform anywhere else in the city.”

After the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, Black business owners flocked to the neighborhood for a sense of security and support. At the time of the Odd Fellows opening, Auburn Avenue, previously known as Wheat Street, had already established itself as a thriving African American community.

What arose along the next decade included businesses like the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, owned by barber turned real estate developer Alonzo Herndon, who later went on to become Atlanta’s first Black millionaire, and the Atlanta Daily World, the first accessible Black-owned newspaper in the U.S.

“We understand what progress is, we understand there has to be diversity, but we also understand that you can’t just take the history out of the community.”

Kimberly Alexander, operations manager for the Oddfellows Building

Auburn Avenue grew also to accommodate growing nightlife, with the opening of the Royal Peacock Lounge — known originally as the Top Hat Club — which would later accommodate artists such as Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong and The Supremes.

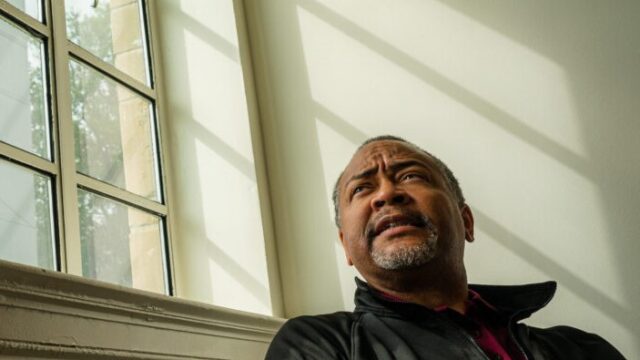

“Sweet Auburn was one of the many examples of African American resistance, post Civil War, post-reconstruction, post-Jim Crow, leading up to what people know as defining the Civil Rights Movement,” said LeJuano Varnell, the executive director of Sweet Auburn Works, Inc., a nonprofit economic development organization created to preserve the history of Sweet Auburn and its neighboring streets.

“We were blessed with having the first Black-owned radio station in WERD, the first Black FDIC-insured bank in Citizens Trust Bank (the building now owned and operated by Georgia State University). They were groundbreaking, but necessities for a segregated African American community in this city in the South to have some form of normalcy and self-respect in how they managed their everyday living.”

The avenue reached its peak in business revenue during the mid-’40s to early ’60s, with Fortune Magazine naming Auburn “the richest Negro street in the world” in 1956.

Black visitors across the country who primarily relied on the Green Book, a guide of Black-owned businesses and lodging, were directed to Auburn businesses like the Royal Peacock, Ma Sutton’s Restaurant and Ebenezer Baptist Church, home to respected pastor Martin Luther King Sr., and his co-pastor/son, Martin Luther King Jr, a figure who Perkins has fond memories of from his days in the community.

“My in-laws and Martin Luther King Jr. were good friends, so he would come over to their house and we would see them a lot,” the Odd Fellows owner said. “I saw him as just an ordinary person. We knew that he had a vision of course, you couldn’t help but know that…he was pretty cool at the time.”

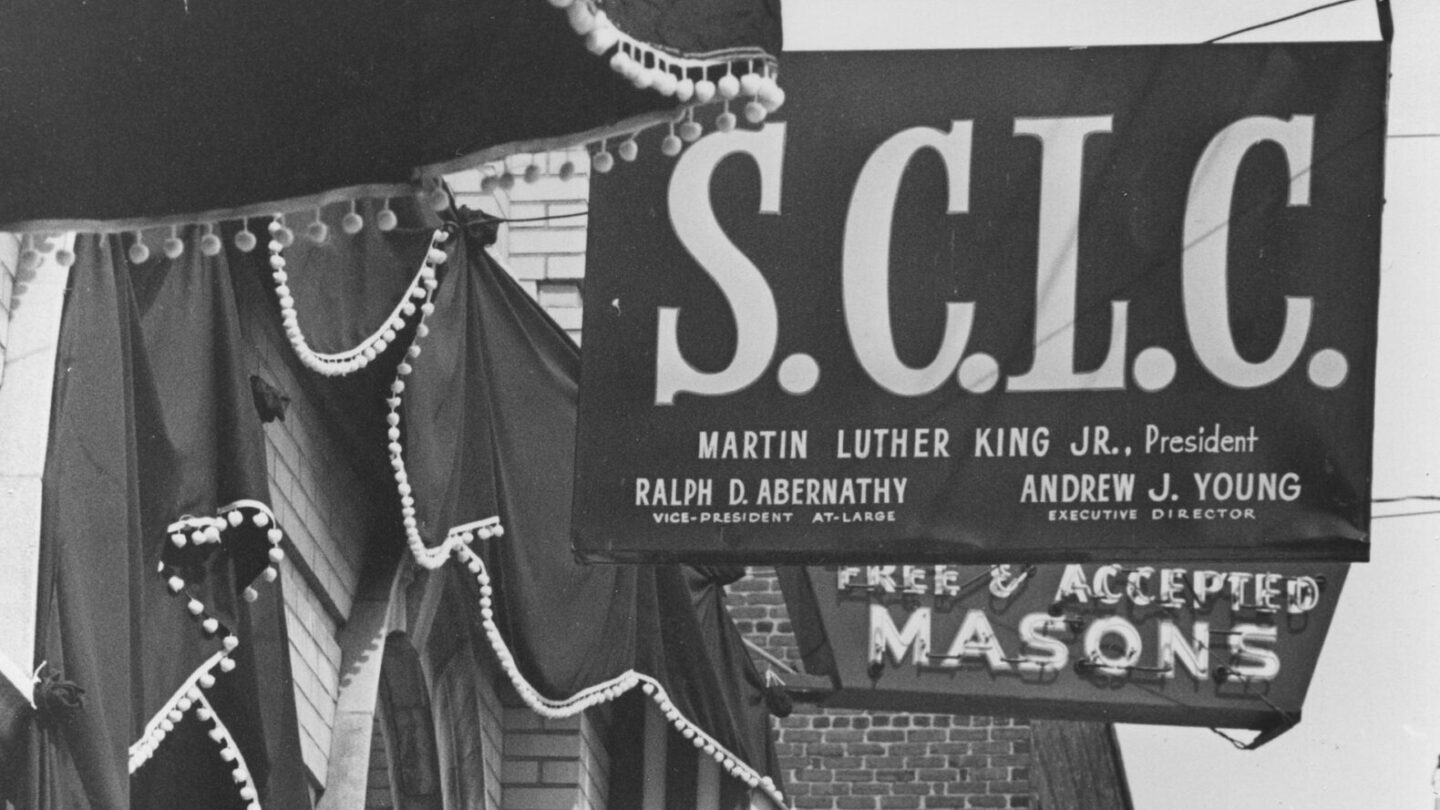

Around this time, Auburn also became a major hub for efforts in supporting the Civil Rights Movement. John Wesley Dobbs, nicknamed the mayor of Sweet Auburn, often organized and coordinated voting registration drives for Auburn residents and founded the Atlanta Negro Voters League.

In addition, the international offices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) set up its foundation on the street, with historical events such as the March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery marches being planned inside of the building.

It was not until the end of segregation in the late 1960s that Sweet Auburn began to see a growing decline, with many residents and businesses moving across other neighborhoods throughout Atlanta that were now available to them for ownership.

The decline continued across the ’80s and ’90s, with crime rising and many economic and infrastructural resources slowly becoming nonexistent. While the street still experienced success with the growth of the King Center, the Odd Fellows renovation and frequent activity at the Royal Peacock, it was still not enough to keep economic activity at the level it was previously.

The disinterest of Sweet Auburn by the city’s residents and government came to a head during the 1996 Olympics when city officials actively dissuaded millions of visitors from patronizing the district.

“They told visitors coming to the city that it was dangerous, to not go down there at night … they had the streets blocked,” said Dan Moore, owner of the APEX Museum, a popular African American history museum that has been a part of the area since its opening in 1978. “Telling them that they would get robbed if they came down here.”

Today, while long-standing attractions such as The King Center and The APEX Museum are still seen as tourism hot spots, and thousands of neighboring Georgia State University students walk alongside the avenue daily, Auburn is a living monument to its former glory.

Black-owned businesses and offices are still at the forefront but lack the promotion and economic revenue enjoyed by Ma Sutton and Alonzo Herndon. Roughly half of the properties, once newly built office buildings or busy beauty salons, are now either bordered up and abandoned or vacant lots.

“We’re running into a lot of obstacles and barriers that we didn’t anticipate,” said Kimberly Alexander, Perkins’ daughter and current day-to-day operations manager for the Oddfellows Building. “It’s a little tougher in this environment because we’re not relying on each other like we used to.”

“This neighborhood has been neglected in its economic development, and as a result of that, we have all the symptoms of what people call ‘blight,'” said Varnell. “We’ve got a lot of vacant lots, vacant old buildings, not a lot of foot traffic, not a lot of residential activity, we’re poorly lit, and as a result, when you have all these places to hide, it’s a breeding ground for bad things to happen.”

Varnell and Alexander describe recent issues in the community ranging from drug activity and gun violence to street racing, with Jackson saying that community leaders have had to pay for their own off-duty officers to prevent crime.

“When we do call 911 when there are disturbances, they never come,” Alexander said.

Perkins and Alexander say after decades of being neglected by the city’s government and elected officials, Mayor Andre Dickens and his administration have begun to take steps towards working to solve rising issues the area faces in regard to crime and economic resources.

“I feel like this administration is more aware and that they are listening and interested in how they can be helpful,” said Alexander. “Do I think it’s enough? I will never think it’s enough.”

And throughout all of the adversity faced, residents still have faith in Auburn to rise back into its glory days as a hub for modern-day African American culture, business and innovation.

Alexander has also noted that with the beginnings of revitalization in the area have come newer parties, such as Georgia State University, subsequent student apartment complexes and other business developers — all eager to buy property for their own usage.

She claims that while she and other neighborhood veterans are not against the coming of new facilities or businesses, they will fight adamantly to make sure that the past of Sweet Auburn is not erased.

“It’s important for us to be good stewards for what they’ve done … to not let this history die. To not let third parties come in here and tell us what it should be because we know what it should be and what it has been. We understand what progress is, we understand there has to be diversity, but we also understand that you can’t just take the history out of the community.”