One of the paradoxes of racial discrimination is the way it can remain obscured even to the people to whom it’s happening. Here’s an example: In an ambitious, novel study conducted by the Urban Institute a few years ago, researchers sent actors with similar financial credentials to the same real estate or rental offices to ask about buying or renting a home or apartment. In the end, no matter where they were sent, the actors of color were shown fewer homes and offered fewer discounts on rent or mortgages than those who were white.

The results even surprised some of the actors of color; they felt they had been treated politely — even warmly — by the very real estate agents who told them they had no properties available to show them but who then told the white actors something different. The full scope of the disparate treatment often becomes clear only in the aggregate, once the camera zooms out.

And yet obscured as the picture may be, black Americans take the existence of discrimination as a fact of life. That’s according to a new study conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, which asked black respondents how they felt about discrimination in their lives and in American society more broadly.

Almost all of the black people who responded — 92 percent — said they felt that discrimination against African-Americans exists in America today. At least half said they had personally experienced racial discrimination in being paid equally or promoted at work, when they applied for jobs or in their encounters with police.

But within that near-consensus, the respondents reported having different kinds of experiences with discrimination, which varied considerably depending on things like gender, age and where they lived.

Take, for example, the question of whether discrimination that was the result of individual bias was a bigger problem than discrimination embedded into laws and government. Among the folks who said that discrimination existed, exactly half of all respondents felt the discrimination that black people face from individual people was a bigger cause for concern. But younger people were more likely to say they felt that institutional discrimination was a bigger concern.

There was also a city-rural divide here, with people who lived in urban areas more likely to see this discrimination as driven by institutional factors as opposed to individual bias than those who lived in rural areas.

How black people saw their neighborhoods

The data from the survey show that black people who reported living in mostly black neighborhoods viewed their communities differently than those who lived in mostly non-black areas. For starters, they were much more likely to describe their community as a low-income neighborhood. And they had more negative views about their neighborhoods, too: Those respondents were more likely to say that crime, housing, the availability of jobs and grocery stores were worse than they were in other places. They were about twice as likely as black folks who lived in mostly non-black neighborhoods to say their local schools were worse off than other places to live. They were also more likely to say the police force in their communities were of a different racial background.

Personal experiences with discrimination

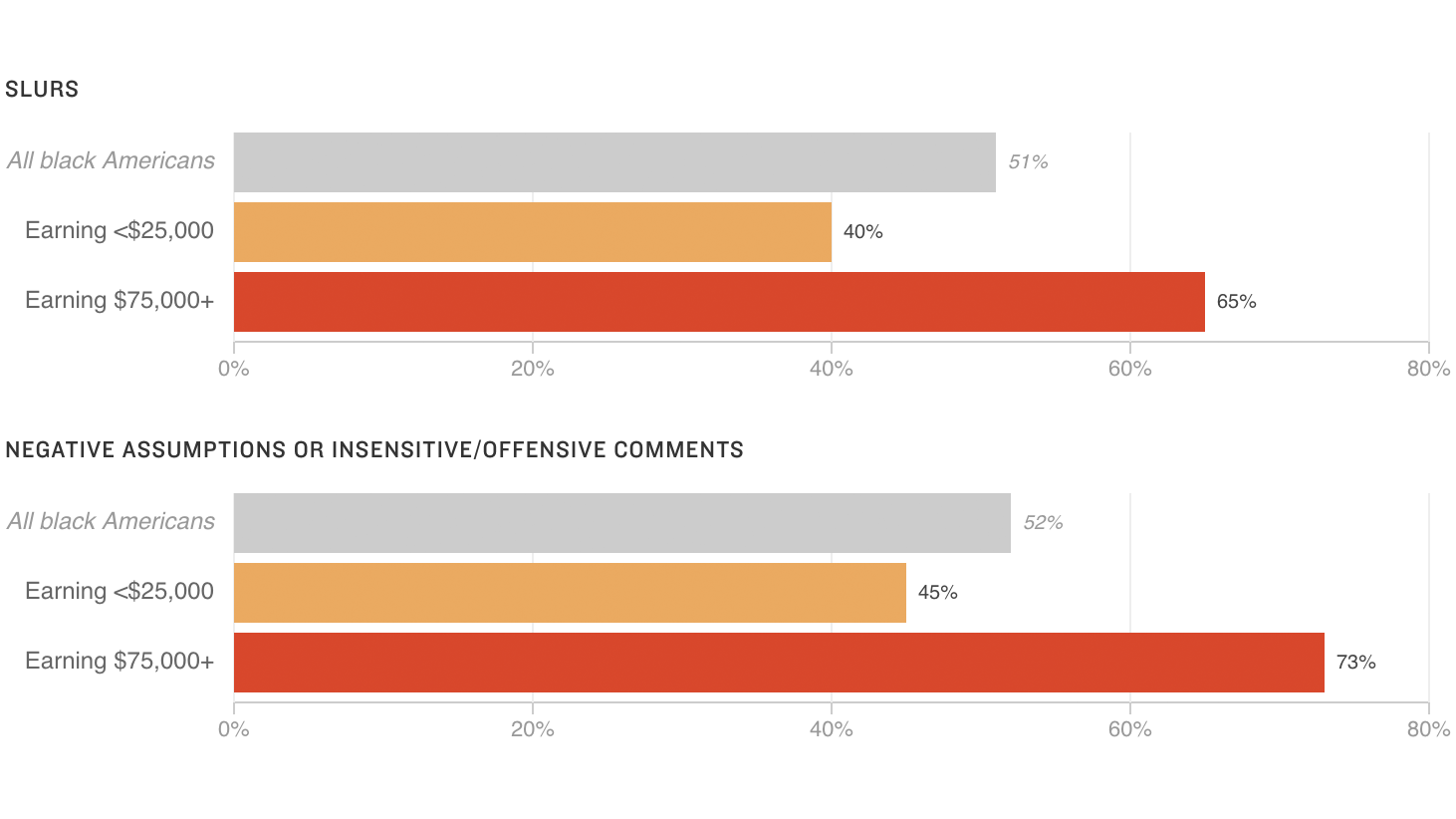

There were some stark differences in the way people in different income brackets said they experienced discrimination. Just about 2 in 3 people who earned more than $75,000 a year said that someone has referred to them or black people with racial slurs; less than half of all people who made less than $25,000 said the same. The same trend was true when respondents were asked whether someone acted afraid of them because of their race: Fifty-five percent of people who made more than $75,000 a year or more said this was true, compared with 33 percent of those who made less than $25,000 a year.

The researchers did not attempt to posit any theories to explain why respondents answered differently based on their incomes. But what could be happening is that higher-income earners might live somewhat less segregated lives and have more chances to have more cross-racial encounters — and more negative cross-racial encounters.

I ran this theory by Phillip Atiba Goff at John Jay College, whose specialty is the psychology of bias and racism. Goff was wary of speculating on statistics from a survey that he didn’t conduct, but he offered this useful bit of context that he called “the bind of black success”: Not only were higher-income black folks in more contact with white people, but they also more acutely experienced the stakes of being direct competition with them. “The more proximity to inclusion is realistic, the price of exclusion is more pronounced,” he explained.

Policing and criminal justice

At least half of the respondents said they had experienced discrimination or unfair stops or treatment by the police. Gender mattered here: Men were more likely than women to say that they had personally experienced discrimination in encounters with the police.

Age mattered, too: Younger people were much more likely than people 65 or older to say that they or a family member had been unfairly stopped or treated by the police because they were black.

But where people lived mattered a lot in people’s feelings about policing. Suburbanites were much more likely to say they were treated unfairly than people in urban areas, and people in the Midwest and the South were much more likely than those in the Northeast to say that they or people in their communities experienced discrimination in dealing with the police.

So what might explain the variation in feeling between suburbanites and city dwellers when it came to policing? The most common reason for contact with police is a traffic stop, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, so it could mean that black people who live in places where cars are more central to everyday life — people who live in the suburbs and not in denser, “pre-car” cities like those in the Northeast — are simply stopped by the police more often.

Not surprisingly, the expectation of discrimination from the police also led many of the people surveyed — about 3 in 10 — to say they avoided calling the police when they were in need. (Low-income respondents were more than twice as likely to say they avoided calling the police.) That finding dovetails with recent research that found that high-profile local instances of police violence — and the subsequent erosion of trust in the police — makes people less likely to call 911.

Taken altogether, these survey results aren’t terribly surprising: They’re backed up by the reams of data that show the extent to which African-Americans are far more likely to live in areas with concentrated poverty even when they are high earners, are more likely to go to segregated and underfunded schools, and more likely to be stopped by the police and searched once they are. Black folks are living objectively more difficult lives than similarly situated white folks.

But here is a sobering thought: What if the black respondents to the NPR survey, who almost unanimously assumed that anti-black discrimination was a given, were like the people in the Urban Institute study and actually underestimating the drag that discrimination exerts on their lives? As data becomes more accessible and granular, we can more easily see how race is often the only variable that explains disparate treatment. If these responses are how people feel about discrimination based largely on what they can glean from their own direct experiences and commiserating with relatives and neighbors, it’s not hard to imagine that the full picture is even less rosy than these data suggest at first glance.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))