When the government made school meals temporarily free to virtually all public school students in 2020, the intent was to buffer children and families from the spike in hunger and economic hardship caused by the pandemic. It also inadvertently turned out to be a pilot project for something anti-hunger groups had been pushing for years: making school food free, permanently, for all public school students, regardless of income.

Once free meals were in place, albeit temporarily, many advocates thought that they would at least remain that way for the rest of the pandemic—if not longer. That didn’t turn out to be the case; this spring, Republicans blocked an extension of the waivers that allowed schools to serve free meals to all, which made the prospect of legislation establishing universal school meals remote.

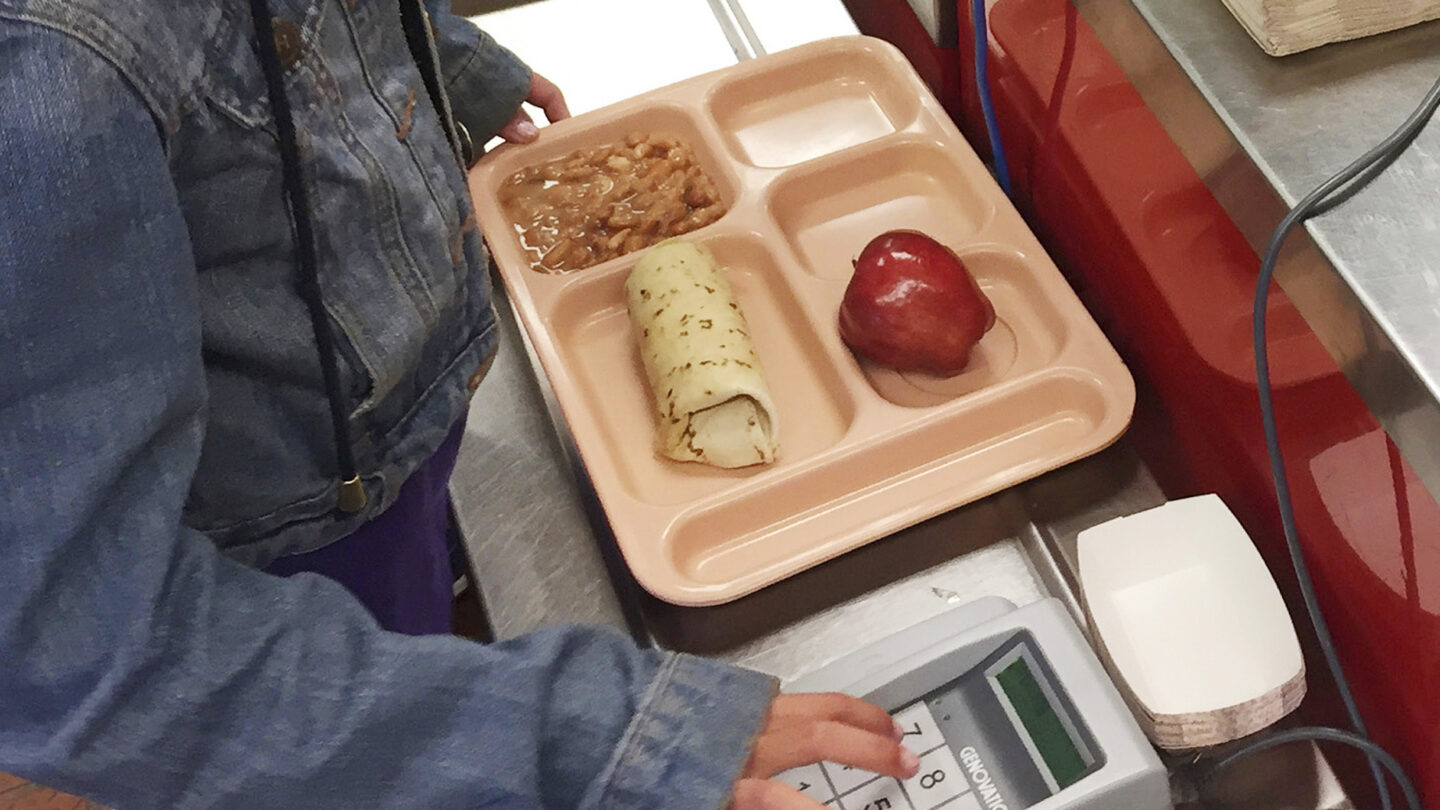

This fall, schools are once again charging for lunch and breakfast, and people who run school food programs are back to the familiar scramble to get students signed up for free and reduced-price meals — and to the familiar worry that some kids will feel stigmatized for getting free meals, end up in lunch debt or go hungry.

Those arguing for universal free meals say that it would put an end to that stigma and to administrative hurdles that can prevent parents from signing their kids up.

While advocates say Republican opposition to expanding school feeding programs is daunting, they haven’t given up on the idea of making school meals free for all. Instead, they’re trying to keep the momentum going by backing state-level efforts that could eventually lay the groundwork for federal action.

States move to free school meals for all kids

This year, California, Maine, Vermont, Massachusetts and Nevada will offer free meals to all public school students, regardless of their family’s income. Connecticut has also funded free meals for part of this year, and Colorado voters will decide in November whether to make school meals free to all. Universal meals legislation has been introduced in a number of other states, including Minnesota, Wisconsin, New York, Maryland and North Carolina.

A state-by-state approach isn’t ideal, says Clarissa Hayes, deputy director of school and out-of-school time programs at the Food Research & Action Center, but it’s still an important step — one that never would have happened if the pandemic hadn’t hit.

“It really moved the needle,” she says. “We are excited to see what’s happening in the states, and in most cases, it is a bipartisan effort and there are a lot of partners at the table.”

But whether action at the state level will translate into more support for federal universal school meals legislation is unclear, says Katie Wilson, the executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance. “You can roll the dice,” she says.

While state initiatives could help popularize the idea of universal meals, they could also give federal lawmakers cover to argue that the question of whether to make meals universally free is best left to state legislatures, she says. That would sell kids short, Wilson says, noting that children’s access to healthy food should not depend on their zip codes.

No matter how much support universal school meals have at the state level, Republican opposition in Congress is formidable, she says.

“Right now, there is just not the desire to do universal school meals at a national level from one side of the aisle,” she says. “So how do you change that? We don’t know. We’ve been trying for decades.”

Federal lawmakers will likely hear from constituents upset that kids’ access to school meals has been curtailed at a time when so many families continue to struggle with food insecurity, and high food and fuel prices, says Diane Pratt-Heavner, director of media relations at the School Nutrition Association.

But she says that passing universal meals legislation, of the sort that Sen. Bernie Sanders, Rep. Ilhan Omar and other Democrats have introduced in recent years, is going to be “an uphill climb.”

Another workaround to help hungry kids

Pratt-Heavner and other advocates point to an upcoming opportunity to increase kids’ access to free school meals in a less sweeping, but still significant way — the child nutrition reauthorization process. Every five years, Congress is required to reauthorize school feeding programs, and it’s a critical chance to strengthen them, advocates say.

Congress is overdue to reauthorize the program, but there was finally some movement in July when House Committee on Education and Labor Chairman Bobby Scott, a Virginia Democrat, introduced a childhood nutrition reauthorization bill that was praised by anti-hunger advocates.

The bill, if enacted as written, would alter the rules governing the Community Eligibility Provision. In its current form, the provision allows schools where at least 40% of students are “directly certified” — that is, enrolled in federal safety net programs like SNAP or TANF or are in the foster care system — to offer free meals to all students at the school, regardless of need.

In the 2021-22 school year, 33,300 schools serving 16.2 million children used the provision, according to a USDA spokesperson — that’s nearly a third of the nation’s 49.5 million public school students.

But advocates say that the program isn’t reaching as far as it could. That’s because under the current rules, schools that have between 40% and 62.5% of their students directly certified still have to pay for a portion of the meals they serve, which not all schools or districts can afford or want to do. It’s only when 62.5% or more of the student body is directly certified that the federal government pays the entire amount.

The Scott bill would change reimbursement rates so that schools would only have to have 40% directly certified students to be fully reimbursed for all meals served. And it would allow schools or districts in which 25% of students are directly certified to participate in the program if they were willing to cover a portion of the cost.

Pratt-Heavner says the bill’s provisions would help many more schools in high poverty communities offer meals to all students. But she says that it still wouldn’t help the economically-stressed families who live in wealthier communities.

“At the end of the day, these meals are important to all students,” she says. “And that’s why it’s important to just offer meals to all students, without an application, just like we offer them textbooks and bus service.”

This story was produced by Ag Insider, a publication of the Food & Environment Reporting Network . FERN is an independent, nonprofit news organization, where Bridget Huber is a staff writer.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))