For Ishmail Thompson, this played out within hours of returning to jail from the hospital. Records show that when he ran away from jail staff during a strip search, an officer pepper-sprayed him in the face and then tried taking him to the ground. According to the records, Thompson fought back and additional officers flooded the area, handcuffing and shackling him.

An officer covered Thompson’s head with a hood and put him in a restraint chair, strapping down his arms and legs, according to the records, and about 20 minutes later, an officer noticed something wrong with Thompson’s breathing. He was rushed to the hospital.

Five days later, Thompson died. The district attorney declined to bring charges.

The DA, warden, and county officials who help oversee the jail did not respond to requests for interviews about Thompson’s treatment, or declined to comment.

Most uses of force in jails don’t lead to death. In Thompson’s case, the immediate cause of death was “complications from cardiac dysrhythmia,” but the manner in which that occurred was “undetermined,” according to the county coroner. In other words, he couldn’t determine whether Thompson’s death was due to being pepper-sprayed and restrained, but he also didn’t say Thompson died of natural causes.

Dauphin County spokesman Brett Hambright also declined to talk about Thompson, but says nearly half of the people at the jail have a mental illness, “along with a significant number of incarcerated individuals with violent propensities.”

“There are always going to be use-of-force incidents at the prison,” Hambright says. “Some of them will involve mentally ill inmates due to volume.”

But the practices employed by corrections officers every day in county jails can put prisoners and staff at risk of injury and can harm vulnerable people who may be scheduled to return to society within months.

“Some mentally ill prisoners are so traumatized by the abuse that they never recover, some are driven to suicide, and others are deterred from bringing attention to their mental health problems because reporting these issues often results in harsher treatment,” says Craig Haney, a psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz who specializes in conditions in correctional facilities.

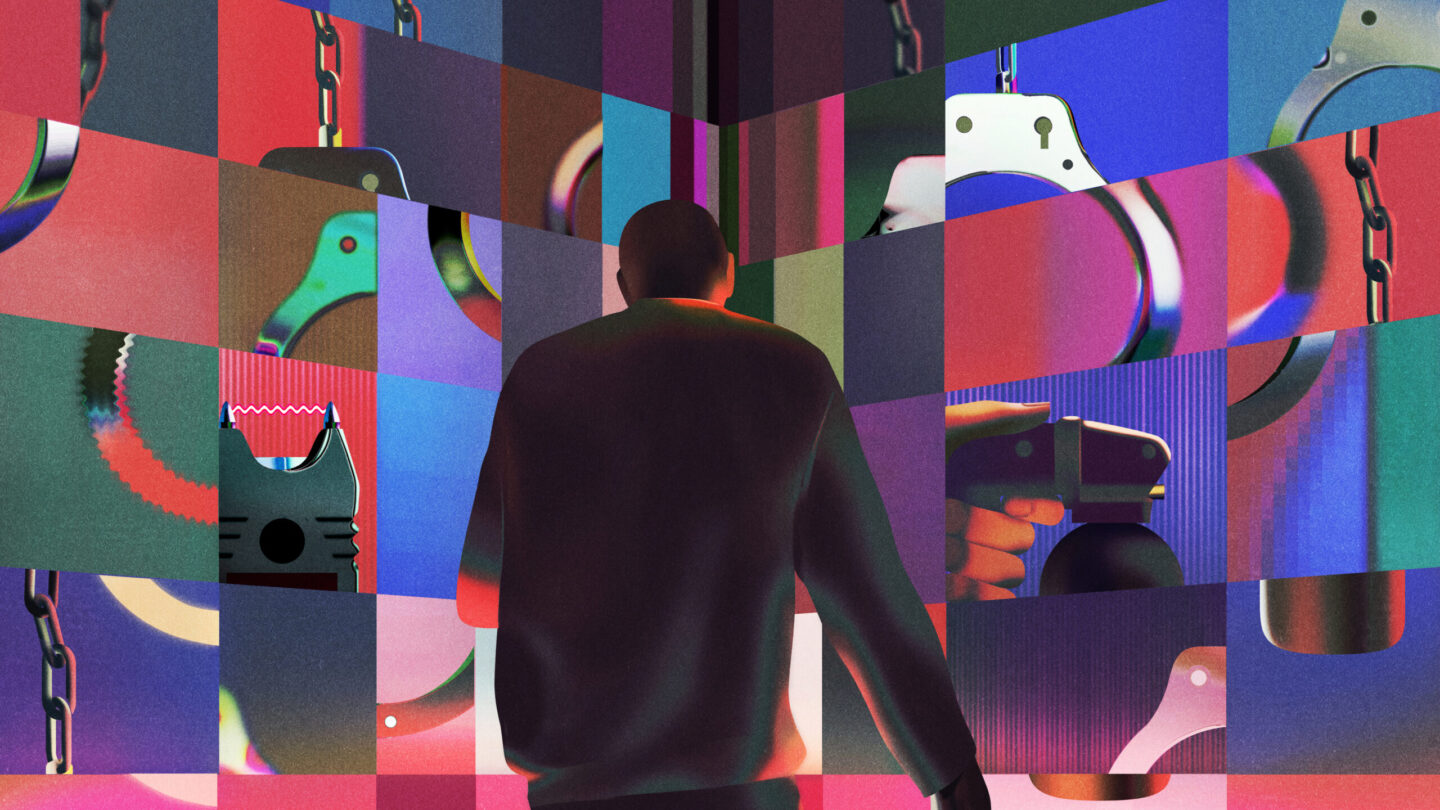

What records reveal about “use of force” in jails

Corrections experts say the use of physical force is an important option to prevent violence between inmates, or violence against guards themselves. However, records kept by correctional officers at the 25 Pennsylvania county jails show that just 10% of “use of force” incidents were in response to a prisoner assaulting someone else. Another 10% describe a prisoner threatening staff.

WITF found that 1 in 5 uses of force — 88 incidents — involved a prisoner who was either attempting suicide, hurting themselves or threatening self-harm. Common responses by jail staff included the tools used on Thompson — a restraint chair and pepper spray. In some cases, officers used electroshock devices such as stun guns.

In addition, the investigation uncovered 42 incidents where corrections staff noted that an inmate appeared to have a mental health condition — but guards still deployed force after the person failed to respond to commands.

Defenders of these techniques say they save lives by preventing violence or self-harm, but some jails in the U.S. have moved away from the practices, saying they’re inhumane and don’t work.

The human costs can extend far beyond the jail, reaching the families of prisoners killed or traumatized, as well as the corrections officers involved, says Liz Schultz, a civil rights and criminal defense attorney in the Philadelphia area.

“And even if the human costs aren’t persuasive, the taxpayers should care, since the resulting lawsuits can be staggering,” Schultz says. “It underscores that we must ensure safe conditions in jails and prisons, and that we should be a bit more judicious about who we are locking up and why.”

“All I needed was one person”

For Adam Caprioli, it began when he called 911 during a panic attack. Caprioli, 30, lives in Long Pond, Pa., and has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and anxiety disorder. He also struggles with alcohol and drug addiction.

When police responded to the 911 call in the fall of 2021, they decided to take Caprioli to the Monroe County Correctional Facility.

Inside the jail, Caprioli’s anxiety and paranoia surged. He says staff ignored his requests to make a phone call or speak to a mental health professional.

After several hours of extreme distress, Caprioli tied his shirt around his neck and choked himself until he passed out. When corrections officers saw this, they decided it was time to respond.

Prison staff often justify their use of physical force by saying they’re intervening to save the person’s life, says Alan Mills, an attorney who has litigated use of force cases and who serves as executive director of Uptown People’s Law Center in Chicago.

“The vast majority of people who are engaged in self-harm are not going to die,” Mills says. “Rather, they are acting out some form of serious mental illness. And therefore what they really need is intervention to de-escalate the situation, whereas use of force does exactly the opposite and escalates the situation.”

After they saw Caprioli with his shirt around his neck, officers wearing body armor and helmets rushed into his cell.

The four-man team brought the 150-pound Caprioli down to the floor. One of them had a pepper ball launcher — a compressed air gun that shoots projectiles containing chemical irritants.

“Inmate Caprioli was swinging his arms and kicking his legs,” a sergeant wrote in the report. “I pressed the Pepperball launcher against the small of Inmate Caprioli’s back and impacted him three (3) times.”

Caprioli felt the pain of welts in his flesh. Then, the sting of powdered chemicals in the air. He realized nobody would help him.

“That’s the sick part about it,” Caprioli says. “You can see I’m in distress. You can see I’m not going to try and hurt anyone. I have nothing I can hurt you with.”

Eventually he was taken to the hospital — where Caprioli says they assessed his physical injuries — but he didn’t get help from a mental health professional. Hours later, he was back in jail, where he stayed for five days. He eventually pleaded guilty to a charge of “public drunkenness and similar misconduct” and had to pay a fine.

Caprioli acknowledges that he makes his problems worse when he uses alcohol or drugs, but he says that doesn’t justify how he was treated in the jail.

“That’s not something that should be going on at all. All I needed was one person to just be like, ‘Hey, how are you? What’s going on?’ And never got that, even to the last day.”

Monroe County Warden Garry Haidle and Monroe County District Attorney E. David Christine Jr. did not respond to requests for comment.

Jails unequipped to cope with psychiatric pain

Jail is not an appropriate setting for treating serious mental illness, says Dr. Pamela Rollings-Mazza. She works with PrimeCare Medical, which provides medical and behavioral services at about 35 county jails in Pennsylvania.

The problem, Rollings-Mazza says, is that people with serious psychiatric issues don’t get the help they need before they are in crisis. At that point, police can be involved, and people who started off needing mental health care end up in jail.

“So the patients that we’re seeing, you know, a lot of times are very, very, very sick,” Rollings-Mazza says. “So we have adapted our staff to try to address that need.”

PrimeCare psychologists rate prisoners’ mental health on an A, B, C and D scale. Prisoners with a D rating are the most seriously ill. Rollings-Mazza says they make up between 10% and 15% of the overall jail population. Another 40% of people have a C rating, also a sign of significant illness.

She says that rating system helps determine the care psychologists provide, but it has little effect on jail policies.

“There are some jails where they don’t have that understanding or want to necessarily support us,” she says. “Some security officers are not educated about mental health at the level that they should be.”

Rollings-Mazza says her team frequently sees people come to jail who are “not reality-based” due to psychiatric illness, and can’t understand or comply with basic orders. They are often kept away from other prisoners for their own safety and may spend up to 23 hours a day alone.

That isolation virtually guarantees that vulnerable people will spiral into a crisis, said Dr. Mariposa McCall, a California-based psychiatrist who recently published a paper looking at the effects of solitary confinement.

Her work is part of a large body of research showing that keeping a person alone in a small cell all day can cause lasting psychological damage.

McCall worked for several years at state prisons in California and says it’s important to understand that the culture among corrections officers prioritizes security and compliance above all. As a result, staff may believe that people who are hurting themselves are actually trying to manipulate them.

Many guards also view prisoners with mental health conditions as potentially dangerous.

“And so it creates a certain level of disconnect from people’s suffering or humanity in some ways, because it feeds on that distrust,” McCall says. In that environment, officers feel justified using force whether or not they think the prisoner understands them.

In Chicago’s jail, a new approach to mental health

To really understand the issue, it helps to examine the decisions made in the hours and days leading up to uses of force, says Jamelia Morgan, a professor at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law.

Morgan researches how a growing number of lawsuits are responding to the problem. Lawyers have successfully argued that demanding that a person with mental illness comply with orders they may not understand is a violation of their civil rights. Instead, jails should provide “reasonable accommodations” for people with a designated illness.

“In some cases, it’s as simple as having medical staff respond, as opposed to security staff,” Morgan says.

But individual cases can be difficult to litigate due to a complex grievance process that prisoners have to follow prior to filing suit, Morgan says.

WITF and NPR filed right-to-know requests with 61 counties across Pennsylvania and followed up with wardens in some of the counties that released use of force reports. None agreed to talk about how their officers are trained or whether they could change how they respond to people in crisis.

To solve the overall problem, wardens will need to redefine what it means to be in jail, Morgan says.

Some jails are trying new strategies. In Chicago, the Cook County Jail doesn’t have a warden. Rather, it has an “executive director” who is also a trained psychologist.

That change was one part of a total reimagining of jail operations after a 2008 U.S. Department of Justice report found widespread violations of inmates’ civil rights.

In recent years, the Cook County Jail has gotten rid of solitary confinement, opting instead to put problematic prisoners in common areas, but with additional security measures whenever possible, Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart says.

The jail includes a mental health transition center that offers alternative housing — a “college setting of Quonset huts and gardens,” as Dart describes it. There, prisoners have access to art, photography and gardening classes. There’s also job training, and case managers work with local community agencies, planning for what will happen once someone leaves the jail.

Just as important, Dart says, jail leadership has worked to change the training and norms around when it’s appropriate to use tools such as pepper spray.

“Our role is to keep people safe, and if you have someone with a mental illness, I just don’t see how Tasers and [pepper] spray can do anything other than aggravate issues, and can only be used as the last conceivable option,” Dart says.

Cook County’s reforms show that change is possible, but there are thousands of local jails across the U.S., and they depend on the local and state governments that set correctional policies, and that fund — or fail to fund — the mental health services that could keep vulnerable people out of jail in the first place.

In Pennsylvania’s Dauphin County, where Ishmail Thompson died, officials agree that the problem — and solutions — extend beyond the jail walls. County spokesman Brett Hambright says funding has remained stagnant amid an increase in people needing mental health services. That’s led to an over-reliance on jails, where the “lights are always on.”

“We would certainly like to see some of these individuals treated and housed in locations better equipped to treat the specificity of their conditions,” Hambright adds. “But we must play the hands we are dealt by the existing system as best we can with the resources that we have.”

Brett Sholtis received a 2021-22 Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism, and this investigation received additional support from The Benjamin von Sternenfels Rosenthal Grant for Mental Health Investigative Journalism, in partnership with the Carter Center and Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting.

To learn more about how WITF reported this story, check out this explainer.

Carrie Feibel edited this story for Shots, and the photo editor was Max Posner.

Copyright 2023 WITF. To see more, visit

WITF.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))