Someone like Erika Hardwick has come to the door of millions of Georgia voters.

A paid canvasser for the New Georgia Project Action Fund, Hardwick was working the southwest Georgia town of Dawson on a warm October afternoon. She was trying to motivate people in the town 135 miles (215 kilometers) south of Atlanta to cast ballots on or before Tuesday.

Hardwick is part of an intensifying effort to contact voters in Georgia, where narrow electoral margins have led political parties and other groups to pour in resources, knowing that driving a few more voters to the polls could make a difference.

Although campaigns spend millions on television and social media ads, research has found that face-to-face contact is more effective in pushing marginal voters to the polls. Democrats are also expanding “relational organizing,” paying people to call or text their friends and acquaintances to urge them to vote.

Those efforts may be bearing fruit in Georgia’s big early voting turnout. More than 2 million people had cast early ballots by mail or in person by the end of the day Wednesday, far ahead of the turnout pace of 2018. New Georgia Project’s figures show people it has contacted face-to-face have been three times as likely to vote early so far this year compared with similar people who have had no contact.

Hardwick used to work at a big hotel in Atlanta, but when the COVID-19 pandemic tanked that business, she moved home to southwest Georgia. Now, in addition to taking college classes and selling cosmetics, she gets paid to get out the vote.

Working off a list on her cellphone, Hardwick cruised up and down blocks in the Black section of Dawson, jumping out of her car when she reached addresses on her list. At most houses, no one answered, and Hardwick left a brochure. Others were home, giving Hardwick a chance to ask people about their plan to vote, about the most important issues in their lives and about who they planned to vote for in Georgia’s pivotal races for governor and senator.

The New Georgia Project, founded by Democrat Stacey Abrams, has devoted itself to bringing voters to the polls who represent a rapidly diversifying Georgia — Black, Latino, Asian and younger voters. New Georgia Project and its associated action fund don’t endorse candidates but push progressive policies broadly in line with Democrats. Abrams, challenging incumbent Republican Gov. Brian Kemp this year after narrowly losing to him in 2018, is no longer associated with the group.

Hardwick’s list avoided surefire voters, instead aiming to contact what some might call infrequent voters. The New Georgia Project instead calls them “high opportunity voters.” The group says it has reached 1.9 million people so far.

Patricia Lee, for example, was undecided about her vote and doubted it would do much good.

“They aren’t going to do what they say they’re going to do,” Lee said.

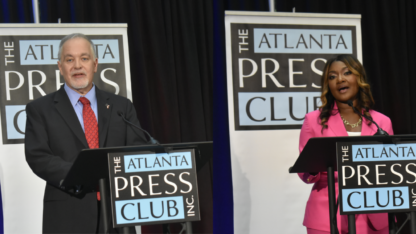

Earnestine Harvey said she would vote for “Abrams all day,” but didn’t know anything about the Senate contest between incumbent Democrat Raphael Warnock and Republican challenger Herschel Walker.

“Child, I don’t even know who’s running for senator,” Harvey told Hardwick.

Plenty of others — including the Democratic and Republican parties, campaigns and other third-party groups — are swarming the doors of Georgia’s 7 million registered voters.

Lauren Groh-Wargo, Abrams’ campaign manager, said Monday that the Abrams campaign has cut television advertising in favor of get-out-the-vote operations aimed at targeted voters.

“We’re firing on all cylinders on our GOTV operation. We are outspending and outmaneuvering Kemp on radio, on digital and on field,” Groh-Wargo said. “And so yes, we are reducing our TV spend.”

Republicans have intensified efforts after barely winning in 2018 and then losing the presidential race in 2020 and two U.S. Senate runoffs in 2021. The Republican National Committee has more than 85 staffers working turnout operations in Georgia, spokesperson Garrison Douglas said, more than five times as many as in 2018. Republicans say they have had more than 4.5 million voter contacts, although some voters have been reached more than once.

“We have to work harder than we ever have before,” Kemp said of his campaign’s turnout push Tuesday after a rally with former Vice President Mike Pence. “We lost, I think, the 2020 race because we didn’t have a good ground game in the state. And we have one now, but we’re not finished with that.”

Beyond parties and candidates, there’s a constellation of liberal-leaning groups aimed at Asian, Latino and Black voters, as well as people motivated by issues such as abortion or health care.

Fewer such groups had existed on the Republican side, but former U.S. Sen. Kelly Loeffler has founded Greater Georgia and affiliated groups aimed at motivating conservatives. That includes some typically Republican voters who didn’t vote in the 2021 Senate runoff that Loeffler lost to Warnock after President Donald Trump falsely claimed that Georgia’s elections were rigged and stolen. Greater Georgia has been making special efforts to persuade those 340,000 people that their votes will be counted.

For Democrats and progressive groups, much effort has gone into trying to improve turnout in rural parts of the state with large Black populations. Some of those counties have historically had lower turnout rates, with Democrats doing more poorly than the number of Black residents suggests they should.

Democrats usually win Dawson and surrounding Terrell County, which civil rights workers dubbed “Terrible Terrell” for its resistance to integration in the 1960s. But Democratic vote shares hover below 55% in a 9,100-resident county that’s 60% Black overall.

“Especially in the Black community, I’ve seen a lot of them think their vote doesn’t count, their vote doesn’t matter,” Hardwick said.

But Hardwick was undeterred. She was moving on, trying to talk to a few more voters before the sun went down.