Grunts, sneaker squeaks and the thud of rackets striking fluorescent yellow-green balls echoed throughout the South Fulton Tennis Center on a hot and humid September weekend.

Seventeen historically Black college and university tennis teams nationwide competed in men’s and women’s singles and doubles to become national champions.

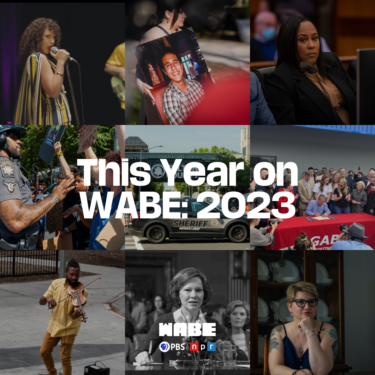

This Year on WABE: 2023

2023 was a big year at WABE. We turned 75, launched WABE Studios, and the WABE Newsroom continued to cover the critical issues Atlantans care about most. Here are a handful of stories, photos, television and podcasts we think stand out from this year.

Make that international.

“I always wanted to play in the U.S. because I want to, like, a scholarship and be able to, you know, be in a university here,” says Alejandra Hidalgo Vega.

Vega is a sophomore at North Carolina Central University (NCCU) and is the reigning Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (MEAC) conference rookie of the year.

Born and raised in Madrid, Spain, she began playing tennis at the age of six with her family. Now, she’s on a full scholarship in Durham, North Carolina.

“I really enjoy being in HBCU — I have a lot of fun,” Vega said.

The experience has allowed Vega to explore the world and learn about African-American culture — one she was unfamiliar with before coming to America.

Vegas says she paid All American Athletics, a Madrid-based recruiting service, to help her land a full scholarship in the United States. She says she had partial scholarship offers from other schools but committed to NCCU before visiting the campus.

Scouting athletes through third-party international sports recruiters has become a big practice in the U.S., including HBCUs and sports like tennis, golf and baseball. That’s according to Dr. Ashley Brown-Grier, a Fulbright U.S. student researcher in South Africa who studies internationalization at historically Black colleges.

“For HBCUs, that works two ways because now we’re able to retain top student athletic talent. And we’re also able to diversify our student bodies,” Brown-Grier says.

According to the NCAA, just under 6,000 international student-athletes competed in 1999-2000. Twenty years later, that number has more than tripled — that includes HBCUs.

However, some students and coaches, such as Tuskegee University’s head tennis coach, Gregory Green, believe HBCUs are moving away from the mission the institutions were ultimately created for.

“We feel that there’s a lot of Black students that need the opportunity to go to college and play tennis,” said Green, adding, “Those are the ones we recruit. And we want to keep it home. This is an HBCU, and we’re going to stick to that all the way through.”

Green has four international students on the roster. But Green says all of them are Black and from Africa.

“There’s no need for me to bring a kid in from Ireland or Switzerland or [Norway] because they’re not helping our community,” he said. “And that’s one of the main missions of HBCUs was to provide our kids the opportunity to be great.”

Green started his coaching career at fellow HBCU Savannah State University in the ’90s. He says HBCUs weren’t always looking to Europe to fill roster spots.

“I don’t know why they started going [with] so much of the student-athletes that don’t look like us,” Green said. “I don’t know why. You should ask Alabama State.”

“Tennis is an international sport.”

Anuk Christiainsz, Alabama State University’s head tennis coach

Anuk Christiansz is Alabama State University’s head tennis coach.

“Tennis is an international sport,” said Christainsz, whose roster is all international students, most from European countries like France, Slovenia and England.

“I would love to see more African Americans playing tennis and get to a level where they can play college tennis at the highest level… But they need to go to the next three, four levels so that they can be on par with everyone else,” Christainsz said.

Christainsz has won six national championships and coached 31 All-Americans during his tenure,

Alabama State’s athletic director backs his coaches’ recruiting tactics, saying diversity is a pillar of his program. And that anytime you’re in a competitive environment, you want the best talent available.

As the landscape for collegiate athletics continues to evolve — including players getting paid for their name, image and likeness — athletic departments at HBCUs will have to find a way to balance winning at their sports with the mission of why the universities were created.