February marks Black History Month, a tradition that got its start in the Jim Crow era and was officially recognized in 1976 as part of the nation’s bicentennial celebrations. It aims to honor the contributions that African Americans have made and to recognize their sacrifices.

Here are three things to know about Black History Month:

It was Negro History Week before it was Black History Month

In 1926, Carter G. Woodson, the scholar often referred to as the “father of Black history,” established Negro History Week to focus attention on Black contributions to civilization. According to the NAACP, Woodson — at the time only the second Black American after W.E.B. Du Bois to earn a doctorate from Harvard University — “fervently believed that Black people should be proud of their heritage and [that] all Americans should understand the largely overlooked achievements of Black Americans.”

Woodson, the son of former enslaved people, famously said: “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

Woodson chose a week in February because of Abraham Lincoln, whose birthday was Feb. 12, and Frederick Douglass, who was born enslaved and did not know his actual birth date, but chose to celebrate it on Feb. 14.

“Those two people were central to helping to afford Black people the experience of freedom that they have now,” says W. Marvin Dulaney, president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), which Woodson founded in 1915 and today is the official promoter of Black History Month.

In the decades after the Civil War and through the racial violence that erupted across the country in the years following World War I, there was a concerted effort to repress the teaching of Black history.

“In the South, they tried to suppress Black history or African American history in the public schools,” Dulaney says, “particularly about things like Reconstruction and slavery, literally distorting the curriculum.”

At the university level, Black studies programs were almost nonexistent, he says. “California was the first state to actually mandate Black history in 1951 for the public schools.”

Largely as a result of the civil rights and Black consciousness movements of the 1960s, “you saw an uptick in Black history courses,” says LaGarrett King, an associate professor of social studies education at the University at Buffalo.

Across the country, public schools “created all these courses and mandates for Black history,” unofficially creating a Black History Month, King says.

The Black press also helped push the idea, says Marcus Hunter, a sociology professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The Chicago Defender, the Philadelphia Tribune, the Baltimore Afro-American … they all started to say that this is something we’re celebrating,” Hunter says.

By 1976, it became official, with President Gerald R. Ford declaring February as Black History Month and calling on the public to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Today, Black History Month is also celebrated in Canada every February and the United Kingdom in October.

There’s a new theme every year

Each year, the ASALH chooses a different theme for Black History Month. This year, the theme is “Black Resistance.”

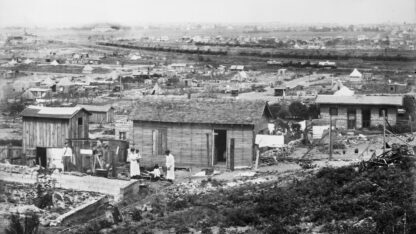

“African Americans have resisted historic and ongoing oppression, in all forms, especially the racial terrorism of lynching, racial pogroms, and police killings since our arrival upon these shores,” the ASALH says of this year’s theme. “These efforts have been to advocate for a dignified self-determined life in a just democratic society in the United States and beyond the United States political jurisdiction.”

Dulaney says this year’s theme was chosen, in part, because of the current politically charged environment around race.

He calls efforts in states like Florida, which recently rejected a new Advanced Placement course covering African American studies, and Alabama, where the State Board of Education has voted to limit how educators can talk about race in the classroom, “a strong retrenchment” against coming to terms with Black history. In light of that, the theme seemed appropriate this year, Dulaney says.

King acknowledges that some people might interpret this year’s theme as politically provocative, but it shouldn’t be seen that way. Rather, it’s an effort to reframe the conversation about Black history around a theme of empowerment, he says.

“With resistance there is an implied understanding of oppression, and it seems to be a segment of the population who do not want to admit those historical facts,” he says. “Yet, resistance helps us understand the power that Black people have in terms of their historical realities, which counters the concept of victimhood that many say drives Black History education.”

Recent controversies over how race is taught echo a time when Black history was often ignored

For Dulaney, the culture wars playing out across the country over how students learn about race feel like a case of history repeating itself.

For many, recent events — the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, for example, and the ongoing controversy surrounding critical race theory, an academic framework stating that people who are white have benefited from ingrained racism in American institutions — look like a recurring pattern, he says.

“I grew up in Ohio and we didn’t learn about a single African or African American man or woman who had ever done anything in history,” the 72-year-old Dulaney says.

“Starting in the ’60s, through the ’70s, we were very successful in integrating African American history of culture into the curriculum,” he says.

However, “now here we are back, having to push that agenda again … [against those] trying to suppress the teaching of African American history and culture.”

King thinks the current controversy surrounding critical race theory will die down. “My personal feelings are that they’ll find another politically manufactured outrage and move on to the next thing,” he says.

UCLA’s Hunter thinks that debate is indicative of where the country is right now. What it really says is “there’s a lot of work to still be done.”

However, Black History Month has been and can continue to be a force for better understanding.

“It offers a certain amount of optimism about what is possible if people actually focus on the educational importance of it,” he says.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))