Jimmy Carter’s path to the presidency is an oft-told story, especially by aspiring presidents trying to be the next politician to defy Washington expectations.

As a little-known Georgia governor, Carter announced in late 1974 that he’d seek the presidency. Atlanta’s largest newspaper answered with a mocking headline: “Jimmy Who?” National media mostly yawned.

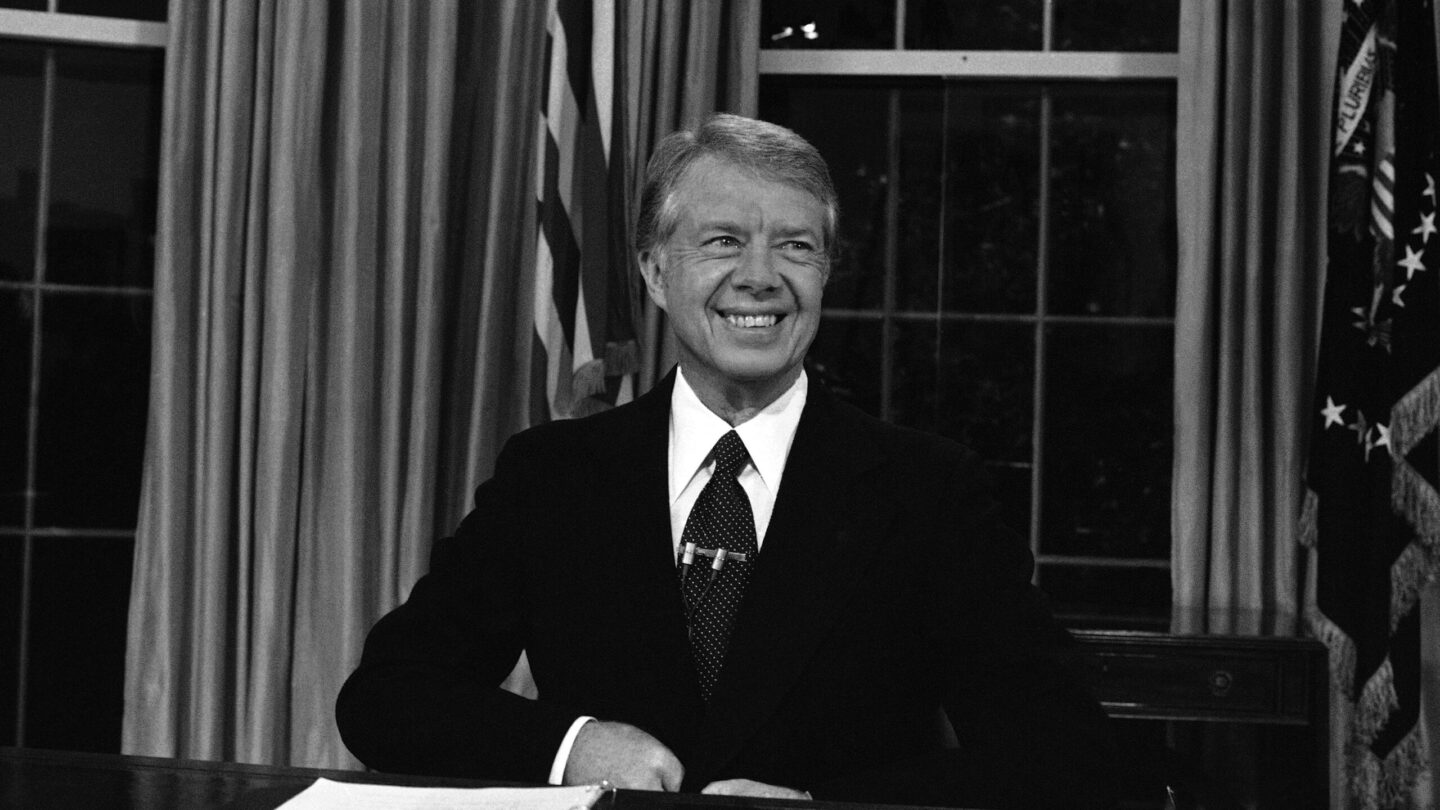

Undeterred, the peanut farmer took his family and friends to Iowa and New Hampshire, where “the Peanut Brigade” set the modern standard for a retail campaign and helped elect Carter as the 39th president.

But the long odds weren’t just about 1976 for Carter, who is 98 and now receiving end-of-life care at his home in Plains, Georgia. Carter’s early life and career were replete with dominoes that could have blocked his White House road before he knew he was on it.

Here are some “What Ifs?” that, had they played out differently, may have made it impossible for Americans ever to answer that mocking question from Atlanta newspaper editors.

The archery farm

Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, now 95, were born in Plains. But Carter’s parents, Lillian and Earl Carter, moved their family in 1927 to a farm in the mostly Black community of Archery, just outside Plains. Thus began Carter’s exposure to divisions of race and class in the segregated, Depression-era South.

Young Jimmy had Black playmates with whom he hunted, fished and fashioned homemade toys. Like their neighbors, the Carters had “no running water, electricity or insulation” and depended on open fireplaces for heat. “We relieved ourselves in slop jars during the night,” Carter wrote in a memoir.

Yet despite the lack of luxury, the future president was still secure in relative privilege, because he was the child of the white, land-owning family at the center of a community where many impoverished Black residents worked for his parents.

One of his earliest influencers was “Miss Rachel” Clark, a Black neighbor and caregiver who was married to the unofficial foreman of the Carter farm. Carter, who spent considerable time at the Clarks’ home, would later say he “knew Rachel Clark in many ways better than my mother.”

Those experiences — seeing the humanity of his Black friends but still living under the white supremacist order of the era — undergirded his public life as a Southern Democrat. He learned early how to navigate an evolving country and party that was stacked with segregationists in Carter’s formative political years before coming to embrace civil rights. Carter did not fight for civil rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s. He campaigned carefully for Georgia governor in 1970, avoiding explicit mentions of race. He won with a small-town, rural coalition of Black voters and white conservatives – then used it to govern more progressively on race than he had campaigned. It was a political tightrope he may never have managed if he’d grown up in the heart of Plains rather than Archery.

‘Mr. Earl’

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter married in 1946 and left Plains to launch his promising career with the U.S. Navy – with no notions of returning except as visitors. But Carter’s father, who had become a prominent merchant and state lawmaker, died in 1953. Carter made the decision, without consulting Rosalynn, to move the young family back home, where the pair built the family farm operations into an impressive peanut agribusiness. Carter joined the local school board and within a decade would run for the Georgia Assembly, further replicating his father’s path. If “Mr. Earl” had lived longer, his namesake might have become an admiral in some far-flung naval post, but never commander in chief.

Election fraud

Carter sought elected office for the first time in 1962, “somewhat quixotically,” he recalled. His Democratic opponent in the state Senate primary was a peanut buyer named Homer Moore. But, the real barrier was Joe Hurst, a neighboring county’s political boss. On Election Day, Carter and his allies caught Hurst pressuring voters and discarding ballots cast for Carter. Quitman County results showed Moore with more votes than registration rolls recorded altogether. Carter challenged the results with the party. After court tussles, Carter ended up on the general election ballot and prevailed. It took a subsequent Senate floor dispute before he was finally sworn in.

The 1966 choice

Carter wasn’t much for the legislature’s back-slapping ways. By 1966, he decided to run for Congress against a heavyweight incumbent, Bo Callaway. Then Ernest Vandiver, a former Georgia governor, dropped out of the governor’s race, allowing Callaway to step into his place against arch-segregationist Lester Maddox. With Callaway’s switch, Carter was on his way to Washington. But the young state senator was bothered by Georgians having to choose between Callaway and Maddox. (In this era, the Democratic nominee was virtually assured a November victory.) Carter tried to recruit a moderate Democrat to run against them but was unsuccessful. So, he recalled, “I decided to relinquish my assured seat in the U.S. Congress and run for governor.”

He lost to Maddox. But the decision was the start of a four-year campaign that resulted in his 1970 gubernatorial win.

No grand plans

History often reveals happenstance in the lives of every president. Carter even chose “Turning Point” as the title of his book about the 1962 state Senate election that changed his career trajectory. Lyndon Baines Johnson won a disputed early congressional race. Bill Clinton lost his first reelection bid as a young Arkansas governor and required a rehabilitation follow-up victory before he reached the national stage a decade later in 1992. George W. Bush narrowly won the Texas governor’s race in 1994, the same night his brother Jeb lost the Florida governor’s race as a favorite. The Texan would be president six years later. Floridian Jeb, once thought of as the political darling in that generation of the Bush dynasty, likely will never be.

Yet the Bushes were a blue-blooded political family already anchored in the national establishment. Johnson and Clinton had no political birthrights but set out from young ages to reach the nation’s highest office. As a young congressman, Johnson even dubbed himself “LBJ,” patterned after Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s moniker, “FDR.”

For Carter, ambition was a driving force generally. But it was not singularly focused.

Carter would serve just one term. His struggles to corral inflation, ease energy shortages and quickly free American hostages in Iran overshadowed achievements at home and abroad. He signed notable legislation on the environment, education and mental health care, and started deregulation of key industries, including airlines. Abroad, he struck a peace deal between Egypt and Israel, normalized relations with China and negotiated treaties turning over control of the Panama Canal.

Carter would say later that he never focused on winning a second term — to his political peril — just as he had no grand design to win his first.

Those four years in the White House “were the pinnacle of my political life,” he recalled around his 90th birthday, but “there was never an orderly or planned path to get there during my early life.”