A federal judge has ordered Georgia election officials to allow computer experts and lawyers to review the databases used to create ballots and count votes.

The ruling came Tuesday in a lawsuit that challenges Georgia’s election system and seeks statewide use of hand-marked paper ballots.

U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg gave the state until Friday to turn over electronic copies of the databases to the plaintiffs’ lawyers and computer experts.

The lawsuit was filed by a group of voters and the Coalition for Good Governance, an election integrity advocacy organization. It argues that the paperless touchscreen voting machines Georgia has used since 2002 are unsecure, vulnerable to hacking and unable to be audited.

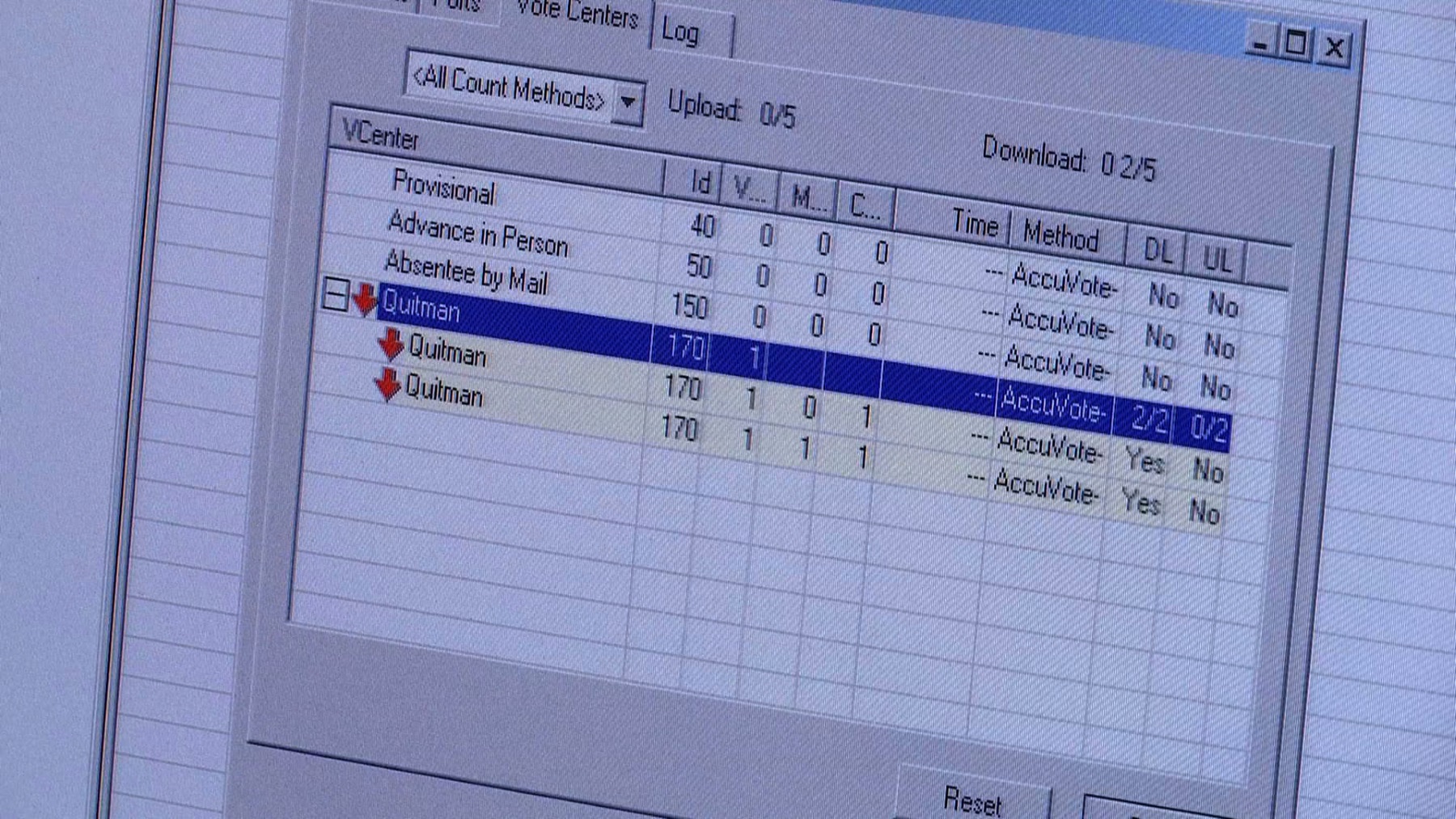

Lawyers for the plaintiffs have argued that they need to inspect the databases at issue because they provide the information that is loaded onto voting machines and then record the cast vote records.

“As such, they provide a roadmap for any coding or configuration errors, security breaches, machine malfunctions, tabulation irregularities or other issues,” according to a court filing laying out the Coalition’s arguments.

They also argued that the information is a public record that should be released.

Lawyers for Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger countered that disclosure of sensitive information in the databases could jeopardize the security of the election system.

Totenberg wrote in her order that the state had not explained how providing an electronic copy of the databases to the plaintiffs’ lawyers and experts under strict security conditions would create a risk of “third-party criminal hacking.”

“The State of Georgia has always treated this critical election infrastructure information as highly confidential,” secretary of state’s office spokeswoman Tess Hammock said in an email. “We are disappointed that Judge Totenberg has ordered us to give sensitive election infrastructure to those who seek to disrupt Georgia’s elections.”

She declined to say whether the state plans to appeal Totenberg’s ruling.

“We’re pleased that the Court saw through the State’s obstruction and provided much needed transparency into an election system that’s highly vulnerable and may already be compromised,” David Cross, a lawyer for some of the voters who brought the lawsuit, said in an email.

Marilyn Marks, who heads the Coalition for Good Governance, accused the secretary of state of stonewalling and said Totenberg’s order would allow much-needed scrutiny.

“If there were errors made in the programming of the machines, there is a good chance that this first look into the configuration of the 2018 election will expose those errors,” she wrote.

The security conditions Totenberg imposed include requiring confidentiality agreements to be signed by the experts and lawyers who examine the databases, as well as any staff helping them. The databases must be kept in locked, secure work rooms during the examination, and any copies are to be installed on no more than six password-protected computers, which must remain unconnected to the internet.

The integrity of Georgia’s election system was questioned during last year’s midterm election in which Brian Kemp, a Republican who was the state’s chief election officer at the time, narrowly defeated Democrat Stacey Abrams to become governor.

Totenberg in September rejected a request to force the state to use paper ballots for the voting that November, saying it would be too chaotic to make the switch so close to the election. But she said at the time that state election officials had too long ignored “a mounting tide of evidence of the inadequacy and security risks” of the voting system, and said further delay would be unacceptable.

Lawyers for Raffensperger argued that concerns about the voting system have been addressed by a new law that provides specifications for a new voting system that state officials say will be implemented in time for the 2020 election cycle.

The lawyers for the coalition and the individual voters have said new machines fitting specifications in the new law also would be problematic, because they still put a computer between the voter and the permanent record of the vote, and aren’t as secure as hand-marked paper ballots. Ultimately, they’ve said, they want Totenberg to block the state from using the new machines, as well as the current machines.

But Totenberg in May declined to toss out the lawsuit, noting that the concerns it raised are still valid given that the state still plans to use the outdated machines in this year’s special and municipal elections. The plaintiff’s requests for copies of the databases are part of the evidence gathering process as the lawsuit moves forward.