A Senate committee tasked with studying how to address dyslexia in schools has submitted its final report to the state legislature. Researchers at Yale University say the learning disability affects about one-in-five people.

Students diagnosed with dyslexia often have trouble identifying sounds in words and understanding that letters represent those sounds, according to the International Dyslexia Association. It is not related to intelligence.

Hearing the Testimony

Starting in August, Georgia’s Senate study committee heard testimony from parents of children with dyslexia, teachers who work with dyslexic students and educational experts.

Pat Warner is the father of a 14-year-old daughter with dyslexia. He told the committee it was hard to get her diagnosed.

“When she was in third grade, her mother and I knew there was a problem,” Warner testified. “She really hit the wall. So, we had a meeting with her teacher, the assistant principal and the principal to discuss the problem. In that meeting, the teacher looked at us and told us, ‘You may just have to accept the fact that you have an average child.’”

Warner and his wife ended up getting their daughter screened for dyslexia privately. She now attends a private school where she can get accommodations, like extra time on tests.

The committee also heard from Sally Shaywitz, a leading expert and researcher at the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity.

Committee chair Sen. Fran Millar, R-Dunwoody, said convincing Shaywitz to come to an October committee meeting was akin to securing an appearance by Beyonce.

“She’s sort of the rock star in all of this,” Millar said.

Shaywitz told the committee that schools generally fail to identify students with dyslexia. On average, schools report between 0 and 4 percent of their students have the learning disability.

According to Shaywitz, studies in which every student is screened for dyslexia show about one in five students have it. Shaywitz said schools can’t know how many children are dyslexic if they don’t screen for it.

“To be counted, you have to be identified first,” she said. “If you’re not identified, you can’t be counted.”

Shaywitz also pointed to 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading scores. The lowest-performing 4th and 8th-grade students scored worse than they did in 2015, signaling a growing gap between high and low achieving students. Shaywitz indicated dyslexia could play a role in poor test performance.

“In dyslexia, it’s not a knowledge gap,” Shaywitz told the committee. “We always want more knowledge, but we have enough to act better. We have an action gap.”

Taking Action

In its final report, the committee made three recommendations to lawmakers.

The first is to develop a college curriculum for future teachers. The university system of Georgia would use the curriculum in teacher training programs to help future educators identify and help kids with dyslexia and other language disorders.

The second recommendation is to screen all Kindergarten students in Georgia’s public schools for dyslexia. The hitch here is that Georgia doesn’t require parents to send their children to school until first grade. So students don’t fall through the cracks, the committee suggests schools allow for screening through the second grade.

The third proposal is to create statewide guidance, teacher training, and evaluation regarding dyslexia. The committee proposes state officials compile a handbook including information about dyslexia and other language disorders. It suggests officials develop required teacher training on dyslexia and other learning disabilities.

Millar, the former chairman of the Senate’s higher education committee, lost his recent election and won’t return to the legislature this year. But he says he thinks lawmakers will support legislation that’s based on the report’s recommendations.

“I’ve already told … a few of my former colleagues if they don’t do this, I’m going to come back and haunt them,” Millar said.

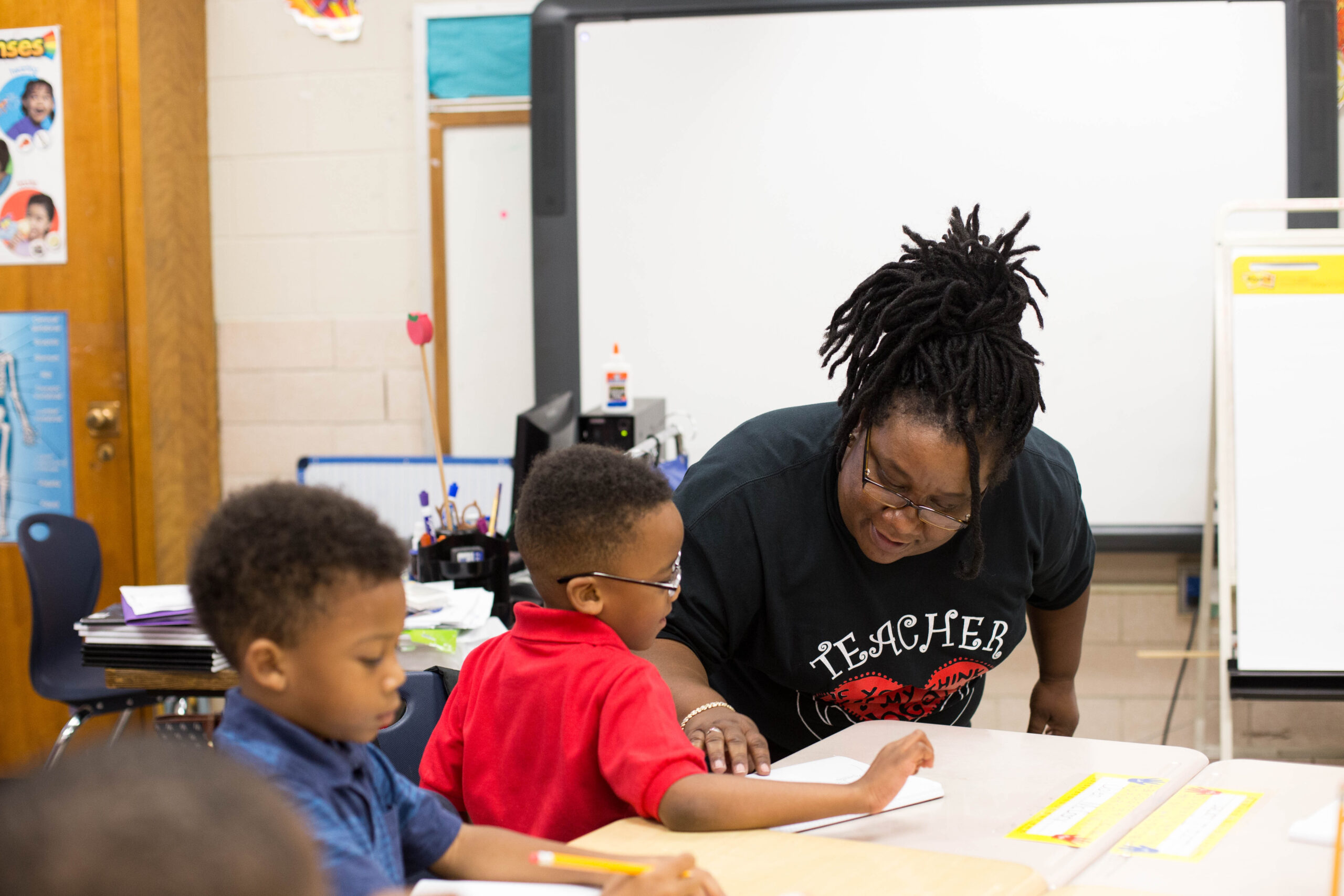

Although few schools currently screen for dyslexia, some local districts have tried to get ahead of the problem by employing strategies — for all students — used to educate those with dyslexia. Marietta City Schools and Atlanta Public Schools both offer elementary school teachers training in Orton-Gillingham, a widely recognized method for teaching students with dyslexia how to read.