A Georgia man scheduled for execution this week didn’t cause the slaying for which he was condemned and should not be put to death, his lawyers argue.

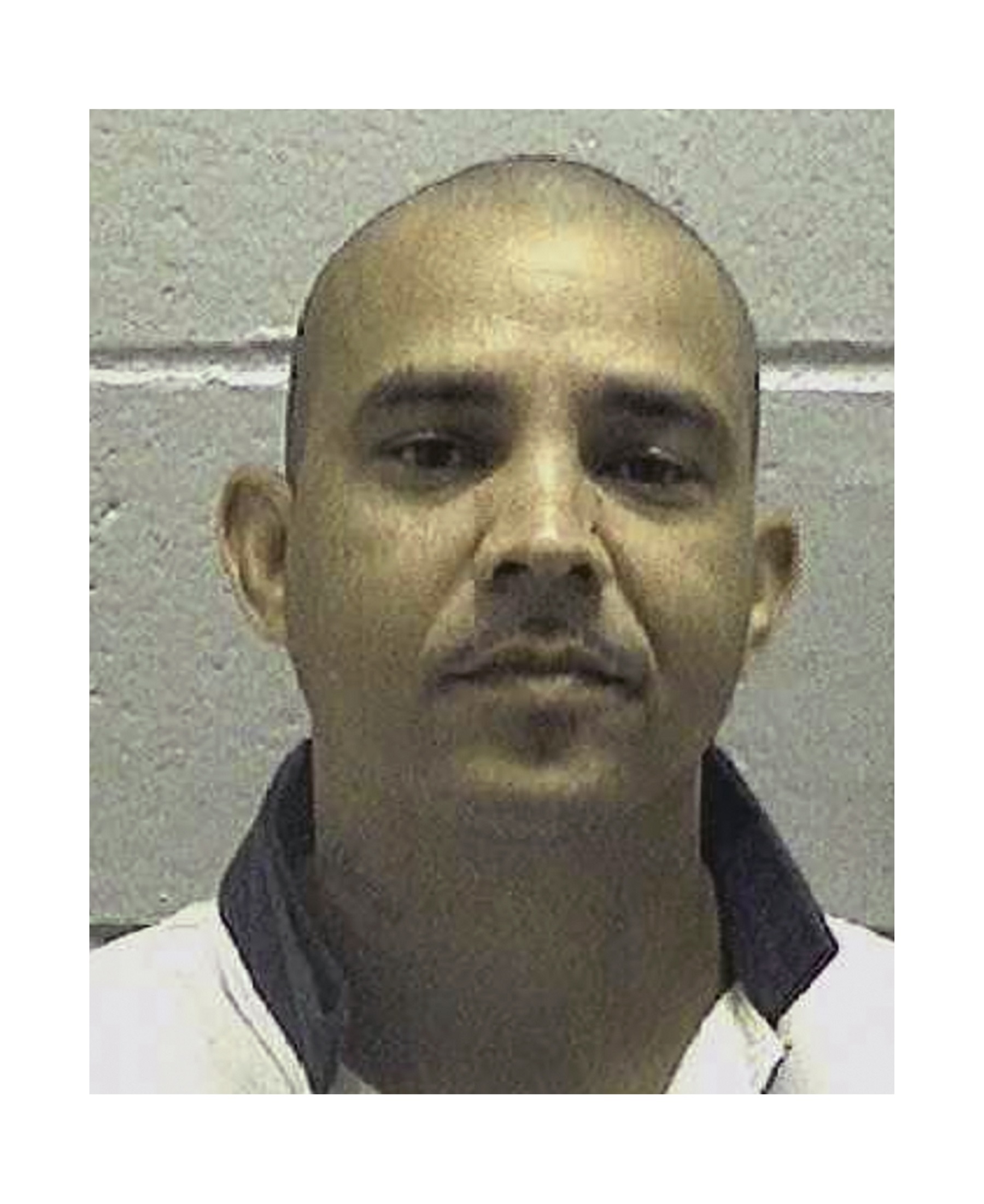

Marion Wilson Jr., 42, is set to die Thursday. He and Robert Earl Butts Jr. were convicted of murder in the March 1996 slaying of Donovan Corey Parks in Milledgeville, about 90 miles southeast of Atlanta.

Butts, who was 40, was executed last year.

The State Board of Pardons and Paroles on Monday declassified the clemency application Wilson’s lawyers filed ahead of a closed-door clemency hearing on Wednesday. The parole board is the only authority in Georgia that can commute a death sentence.

Wilson’s lawyers describe a childhood characterized by abuse, neglect and instability that led him to engage in criminal behavior that escalated as he got older. They argue his trial lawyers failed to present evidence of brain impairments likely caused by his mother’s use of drugs and alcohol during pregnancy and failed to counter prosecutors’ misstatements and exaggerations.

While there was enough evidence to convict him, it doesn’t support a death sentence, Wilson’s lawyers argue.

A witness heard Butts ask Parks for a ride at a Walmart store on March 28, 1996, prosecutors have said.

Butts was in the front passenger seat and Wilson was in the back as they left the parking lot, according to court filings. Parks’ body was found lying face down on a nearby residential street a short time later. Butts and Wilson fled in Parks’ car, later burning it after trying unsuccessfully to find someone to buy it, prosecutors said.

“Marion Wilson admittedly should not have been in Donovan Parks’ car that night, but he was not the man who shot Mr. Parks causing his death,” Wilson’s lawyers wrote.

While Wilson suspected Butts planned to rob someone, he didn’t know Butts meant to harm or kill anyone, they wrote.

Former Ocmulgee Judicial Circuit District Attorney Fred Bright, who prosecuted both men, testified under oath years later that he believed Butts was the shooter.

During the sentencing phase of Wilson’s trial, Bright told jurors “without a shred of evidence” that Wilson shot Parks, Wilson’s lawyers wrote. But during the sentencing phase of Butts’ trial a year later, Bright told jurors the state had proved Butts pulled the trigger.

“That the prosecution falsely maintained that Marion was the shooter in order to obtain the death penalty was, and still remains, highly unethical and contrary to the State’s higher duty of probity and truthfulness in any criminal proceeding,” Wilson’s lawyers wrote.

Bright also exaggerated Wilson’s juvenile criminal record and provided misleading speculation on Wilson’s gang involvement, the clemency application says.

Bright died last year. But Putnam County Sheriff Howard Sills, who was the Baldwin County chief deputy sheriff when Parks was killed, said Wilson called himself the “enforcer” for a violent gang and that both men were responsible for Parks’ death.

“No, we don’t know which one of them pulled the trigger, but we do know without any doubt that Marion Wilson and Robert Earl Butts, acting in concert together as parties to the crime, robbed and murdered Donovan Parks,” Sills wrote in a letter to the parole board.

He wrote that Wilson has “lived one continuous life of crime” from the time he was very young and “has demonstrated no respect for the law and astonishingly no respect for life itself.”

Before Wilson’s trial, Bright offered him a plea deal that would include the possibility of parole, his lawyers wrote, noting that Bright never offered Butts a deal.

Wilson’s lawyers ask the parole board “to consider Marion’s rejection of the plea deal as the unsurprising response of an immature youth whose abysmal childhood and accompanying lack of judgment led him to make poor choices about the course of his life.”

They urge the board to give him another chance at a life sentence with the opportunity “to prove himself worthy of parole” or, alternatively, to resentence him to life in prison without parole.

Wilson’s lawyers are also seeking a new trial and DNA testing on the necktie worn by Parks. They say the necktie was critical to the prosecution’s argument that Wilson pulled Parks from the car and shot him.

A judge has rejected that request. Wilson’s lawyers are asking the state Supreme Court to halt his execution and hear an appeal of the lower court’s ruling.