Schools in poor areas often suffer from a problem they can’t easily fix: student mobility. That’s when families move around a lot, causing turnover in school communities.

The Atlanta Public Schools has been raising money to revitalize some schools, so families want to stay in the surrounding neighborhoods.

Investing in Futures

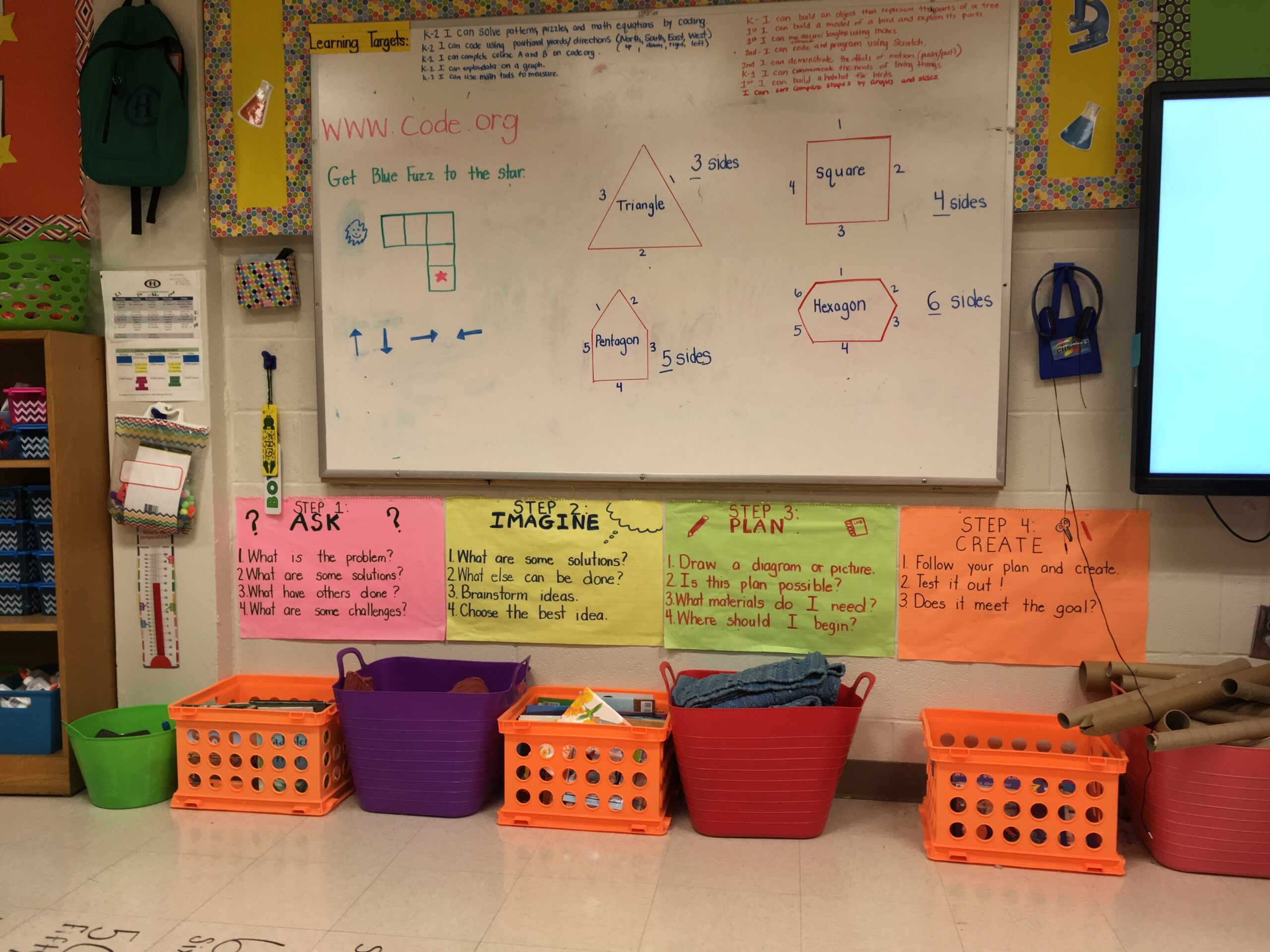

Hollis Innovation Academy is brand new K-8 school on Atlanta’s West Side. It has an academic focus on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM). It serves two of Atlanta’s poorest neighborhoods — Vine City and English Avenue. The West Side Future Fund has pledged more than $16 million to Hollis over five years, with companies like Coca-Cola, the Chick-Fil-A Foundation, Delta, and Sun Trust Bank all donating.

Atlanta-based technology company NCR recently gave Hollis $1 million to support the school’s STEM partnership with Georgia Tech.

“We believe that everyone has equal potential, but not equal opportunity,” said NCR Foundation Lead Yvonne Whitaker. “And so, what we’re trying to do is provide that opportunity.”

Hollis Principal Diamond Jack said that’s exactly what the money will do for Hollis students.

“An investment like this means our kids are getting access and opportunity to extended learning over the summer that they normally would not have,” Jack said.

APS opened Hollis after closing Bethune Elementary School. The new academy is housed at the former Kennedy Middle School. During the 2016-17 school year, the year Hollis opened, it’s student mobility rate was 60 percent. In other words, almost two-thirds of the student population cycled in and out during the year.

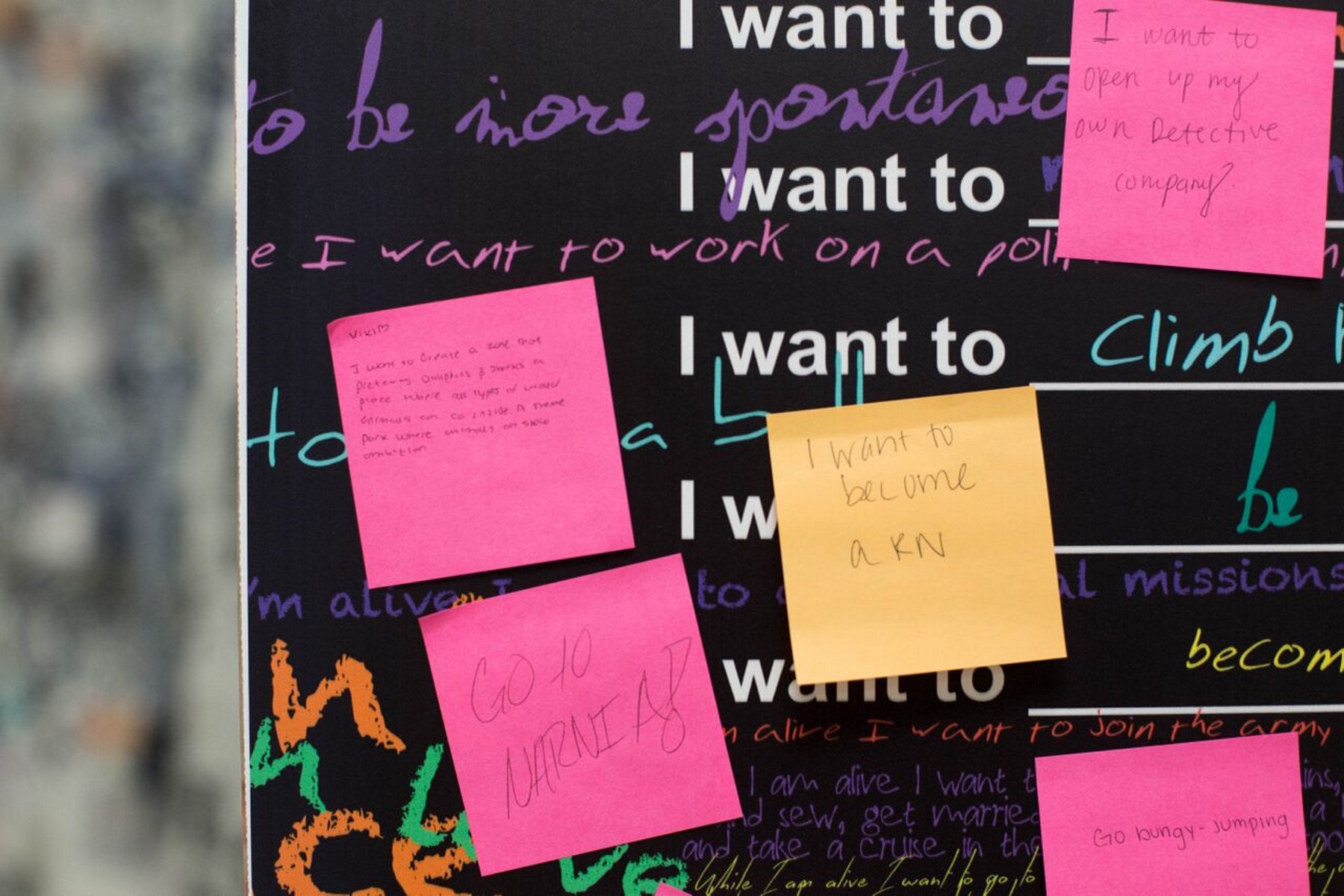

Jack, the school principal, is trying to change that. Part of her strategy is to make school a stable place. She wants the kids to feel like it’s is their home.

The school is divided into the ‘Houses of Hollis.’ Kindergarten and first grade share a house; second and third grade share one; and fourth and fifth grade share another house.

“That’s why we work so hard to make this a crew-like environment,” Jack said. “This is your home. We have houses here. Because I need them to feel like this is ok. I can stay here. I can be safe here.”

To reinforce the idea that kids are safe at school, APS partnered with healthcare groups to help build clinics at five schools, including Hollis. In addition to students, the clinics provide medical and dental care to the entire community.

What’s the ROI?

It may be years before APS knows whether it’s school turnaround plan will work, and whether its efforts and partnerships are successful in stabilizing Atlanta neighborhoods. But Russell Rumberger, a professor emeritus at Stanford who has researched student mobility, says the plan is promising.

“Anything that can keep families stable and kids stable in their schools is a good thing,” Rumberger said. “Changing schools is not a good condition for most kids, so anything that would kind of reduce both residential mobility and school mobility or student mobility would be would be a benefit.”

Rumberger said if schools are serious about reducing their mobility rates, there are plenty of steps they can take without spending much money.

“…things like discipline policies, academic rigor, school spirit, things like that,” he said. “Whatever it is that that enhances the quality of the school that will be reflected in parents wanting to stay there.”

At Hollis Innovation Academy, there are some early signs of excitement. Kindergartener Mark Ruffin takes a break from working with a volunteer to explain why he likes school.

“I can learn and get smarter,” he said.

The adults at Hollis hope kids like Mark will take his enthusiasm home, and tell their parents how much they like school. That’s how leaders hope change will happen: student by student, family by family.

Here are links to Part I and II of this series.

This series is part of an NPR education reporting fellowship.