A shift to mail voting is increasing the chances that Americans will not know the winner of November’s presidential race on election night, a scenario that is fueling worries about whether President Donald Trump will use the delay to sow doubts about the results.

State election officials in some key battleground states have recently warned that it may take days to count what they expect will be a surge of ballots sent by mail out of concern for safety amid the pandemic. In an election as close as 2016’s, a delayed tally in key states could keep news organizations from calling a winner.

“It may be several days before we know the outcome of the election,” Jocelyn Benson, Michigan’s Democratic secretary of state, said in an interview. “We have to prepare for that now and accept that reality.”

Ohio’s Republican secretary of state, Frank LaRose, pleaded for “patience” from the public. “We’ve gotten accustomed to this idea that by the middle of the evening of election night, we’re going to know all the results,” LaRose said Wednesday at a forum on voting hosted by the Bipartisan Policy Center. “Election night reporting may take a little longer” this year, he warned.

Delayed results are common in a few states where elections are already conducted largely by mail. But a presidential election hasn’t been left in limbo since 2000 when ballot irregularities in Florida led to weeks of chaos and court fights.

For some election experts and Democrats, the prospect of similar uncertainty is especially worrisome this year, as Trump disparages mail-in voting as fraudulent and has claimed without evidence that widespread mail balloting will lead to a “rigged” election.

“It’s very problematic,” said Rick Hasen, a University of California-Irvine law professor. “There is already so much anxiety about this election because of the high levels of polarization and misinformation.”

Hasen is among the experts who have been studying the strains on the U.S. electoral system during the pandemic. He recently convened a bipartisan group of academics to recommend safeguards for a disputed election. Some members have gamed out dramatic scenarios like state legislatures or governors refusing to seat electors, or a candidate refusing to cede power.

Meanwhile, some Democratic operatives, lawyers and even the presumptive presidential nominee have grown increasingly vocal with their concerns that Trump will try to meddle in the election. Joe Biden recently said he thinks Trump may use his office to intervene: “Mark my words, I think he is going to try to kick back the election somehow, come up with some rationale why it can’t be held.”

Trump campaign spokesman Ken Farnaso called the accusation “another unsubstantiated creation of the liberal conspiracy theory machine.”

Trump said last year in an interview that he would accept the results of the 2020 election. Since then, however, the coronavirus has dramatically changed how Americans vote.

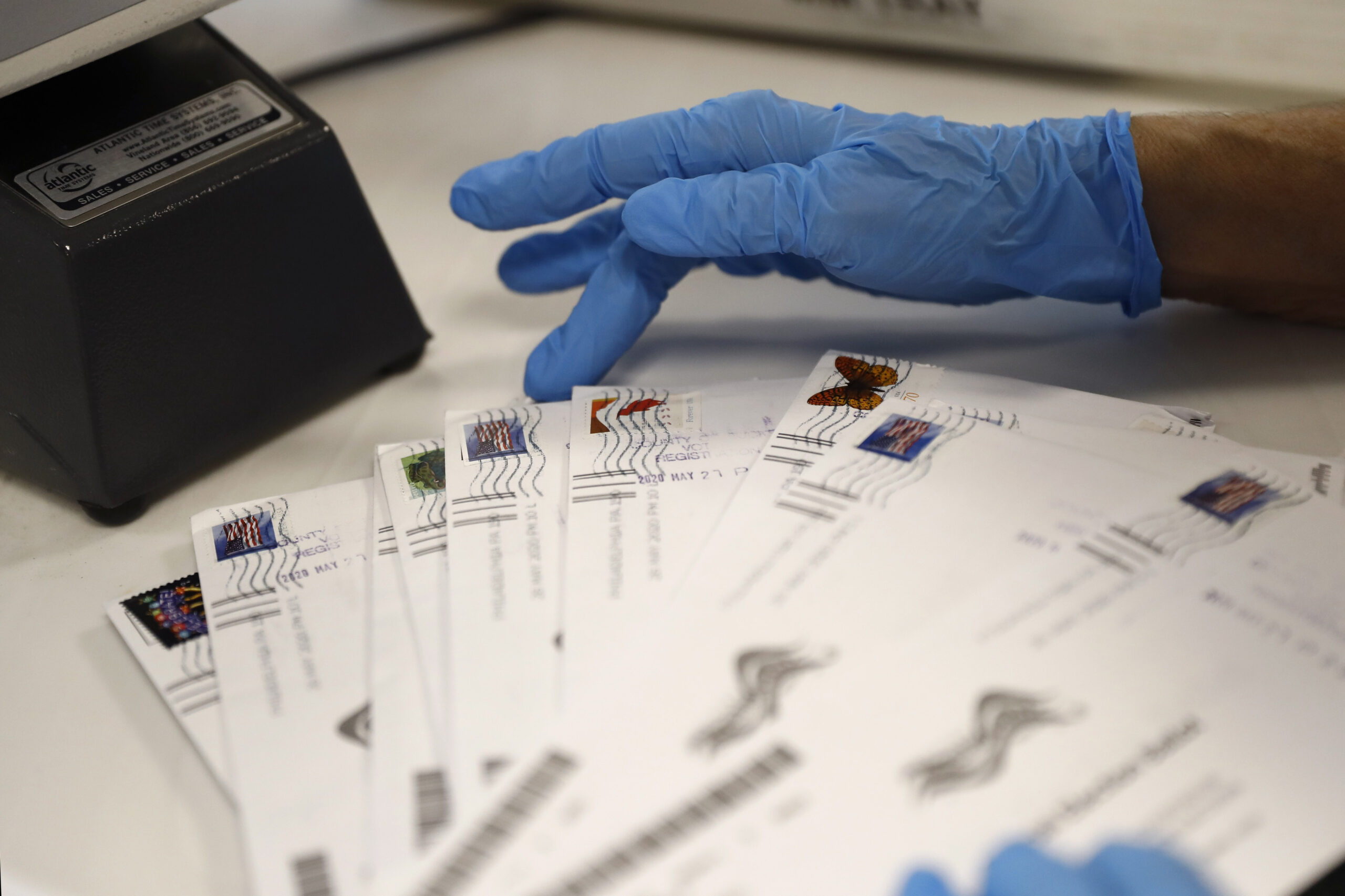

As voters look for a safer alternative to in-person voting, election officials from both parties have promoted mail-in and absentee voting options, and requests for mail ballots have surged in the primaries. Many states expect to be scrambling to process millions more in November.

While each state runs its own process, those mail ballots can take longer to count. In some states, the ballots can be accepted several days after Election Day, as long as they are postmarked before polls closed. And while some states count the ballots as they come in, others — notably the critical battlegrounds of Michigan and Pennsylvania — have laws that forbid processing mail ballots until Election Day, guaranteeing the count will extend well past that night.

That doesn’t mean The Associated Press and other news organizations won’t call a winner. The AP regularly calls races before the official vote count is complete, using models based on partial results, past races and extensive polling.

But in particularly tight contests, the AP and other news organizations may hold off on declaring a winner. That could lead to a national roller coaster ride of shifting results.

In Arizona in 2018, for example, Republican Martha McSally was narrowly winning the initial tally of in-person votes and mail ballots that had arrived days before Election Day. More than a week later, after election officials were able to tally all the mail votes that arrived on Election Day, Democrat Kyrsten Sinema won the senatorial race by more than 2 percentage points. Arizona changed its procedures to try to speed up the vote count this year.

In Michigan and Pennsylvania, two states that helped hand Trump his 2016 victory, Democrats have pushed to relax the laws forbidding them from processing ballots before Election Day but faced GOP resistance.

In Michigan, GOP leaders had argued it would be improper to handle ballots before Election Day. But on Wednesday, the state’s GOP-controlled Senate signaled a shift, advancing a bill that would allow the processing of absentee ballots the day before Election Day. Benson said even if the bill passes, she expects a slow count in November.

“It’s certainly going to be a challenge,” Benson said.

In Pennsylvania, only 4.6% of the state’s voters voted either early or by mail in 2016. But now both parties are urging voters to send in mail ballots for next week’s primary elections, and officials are overwhelmed by absentee ballot requests.

Philadelphia says it won’t even begin to count mail ballots until after the end of primary day, June 2. Forrest K. Lehman, elections director in Lycoming County in central Pennsylvania, warned: “In terms of November, if they don’t let us start canvassing sooner than the day of the election, there’s no way anyone can responsibly call Pennsylvania on election night.”

Another factor that could delay the count is Democrats’ push to require states to accept mail ballots postmarked on Election Day. Democrats have filed more than a dozen lawsuits demanding that standard and note that the U.S. Supreme Court required it for Wisconsin’s April 7 election.

But, because of that requirement, Wisconsin couldn’t release results from its election until April 13.