The morning after the Feb. 14, 2018, school shooting in Parkland, Fla., a middle school teacher in nearby Miami stood in front of his speech and debate class and had no idea what to say.

“It’s a powerful thing when 13-year-olds and 14-year-olds are looking up to you for an answer to something that you don’t have an answer for,” said Kelsey Major, a teacher at Everglades K-8 Center, a public school about 50 miles south of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where 17 people had been killed in the shooting.

“In speech and debate, I was speechless,” he said.

What started as a loss for words later became a group civics project aimed at ending gun violence.

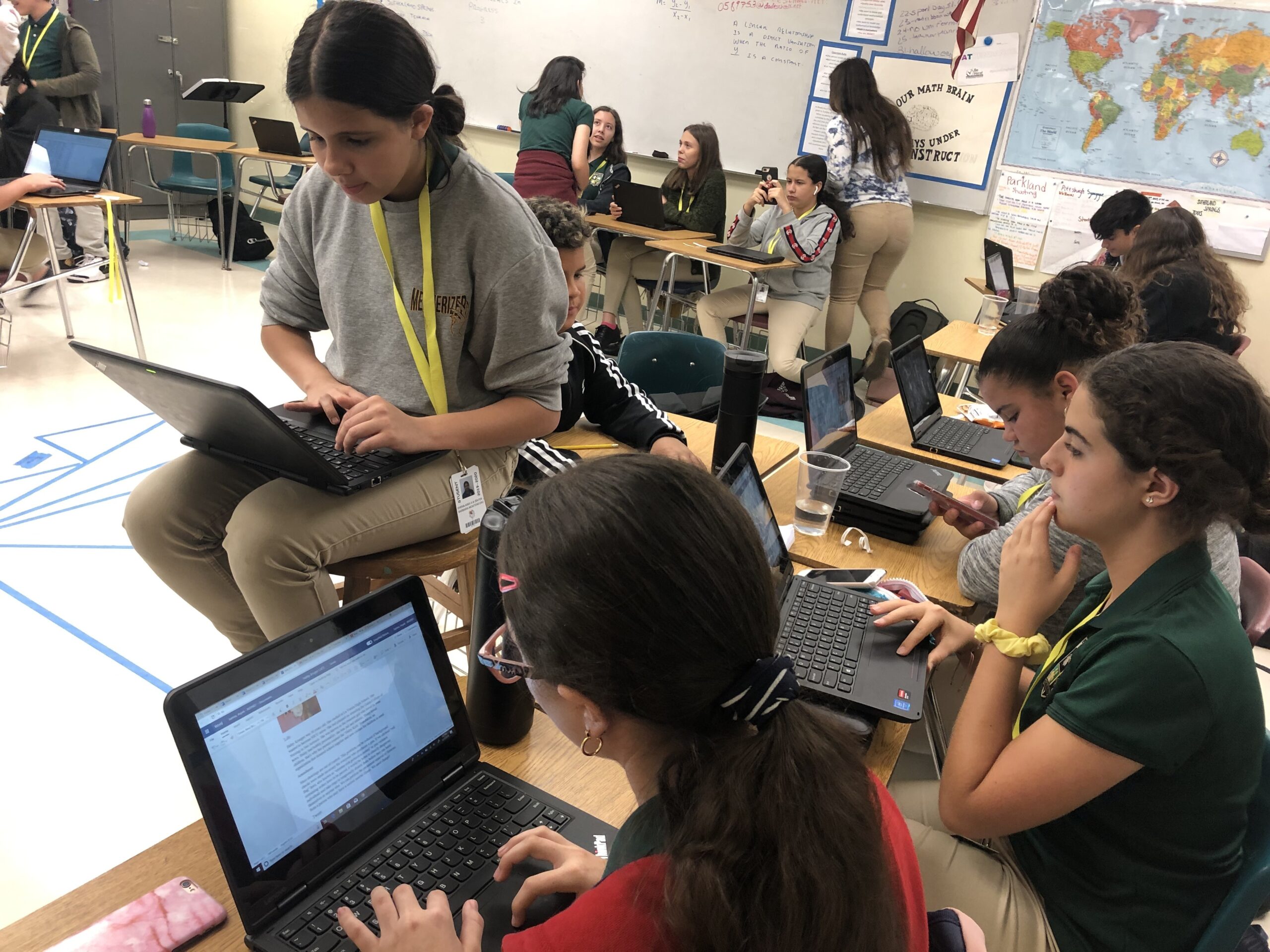

A club of about 40 sixth, seventh and eighth graders are now working on their second edition of a magazine designed to persuade federal lawmakers to pass legislation that would help prevent mass shootings. They’re pushing for a range of policy changes, including further limits on gun ownership, “red flag” laws to keep guns away from potentially dangerous people and greater investment in mental health care in schools.

The publication, called First Shot, features persuasive essays about gun reform policies, short biographies and drawings of victims, data analysis of mass shooting statistics and poetry. This year, the focus is on shootings in “safe and sacred places,” such as schools and houses of worship.

The group is trying to raise money to print a copy of the magazine for every member of the U.S. House and Senate — all 535 of them.

The students are also planning a bus trip in March to deliver the magazines to the local offices of federal lawmakers who represent South Florida. The offices of U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, a Republican, and Reps. Debbie Mucarsel-Powell and Donna Shalala, both Democrats, are on the students’ itinerary, as are state legislators and school board members. The field trip is being funded with a $1,250 grant from The Education Fund, a nonprofit that supports public school teachers in Miami-Dade County.

“Our goal is for all of them to listen to us, the youths, because we are the future,” said eighth grader and club member Susana Martinez. “That’s what legislators always say — that we are the future. But what about the now?”

Fellow eighth grader Angelina Cotnam, who is one of the group’s leaders, wrote a harrowing poem for the magazine that depicts a school shooting from the perspective of a student hiding in a classroom.

She described kids “crowd[ing] together like rats” in corners of classrooms during lockdown drills. She depicted students texting family or friends as they fear for their lives: In the corner, a light shines with a final goodbye.

Cotnam said it’s scary that adults seem to be helpless when it comes to mass shootings, unable to stop them.

“It’s terrible to know every time we have an alarm or a drill — we don’t know if it’s a drill or not, it could be real — that it could be our last day seeing our friends and our parents and everyone we care for alive,” she said.

Acknowledging that gun violence is an emotionally difficult topic for young people, Major asked a colleague to attend the club’s meetings specifically to look after students’ mental health. Special education teacher Olga Carballo said she practices mindfulness and leads breathing exercises with students. If she notices students who seem depressed or anxious, she refers them to the school’s counselor.

“We would not have even introduced this — this would be inappropriate if students were not being killed in schools,” Major said. “But the mere fact that students are being harmed in schools in these mass shootings, and it seems as if very little is being done, we know that the topic is appropriate. But we do take care.”

In the fall, Major gave a presentation to other Miami-Dade teachers about how the magazine project could be replicated and even applied to other issues, like climate change and human trafficking.

He said the club doesn’t have a specific political agenda, and the student members’ views aren’t all the same. Some have parents who own guns, while others think the Second Amendment should be scaled back.

Sometimes, the students disagree.

“We’re humans,” Major said. “When the kids get into the partisan debates, we redirect it right back to … our common goal.”

That’s making sure that when students go to school in the morning, they come home safely in the afternoon. That shouldn’t be controversial, he said.

“If we can get this generation to be above politics, we can be in a better place,” he said.

Copyright 2020 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit

WLRN 91.3 FM.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))