It was one year ago when Republican state Rep. Barry Fleming kicked off two hours of debate on the floor of the state House over how Georgians would cast their votes securely, in the age of computer hacking and international election interference.

“Today, in passing House Bill 316, we can put our voters first in Georgia…” Fleming began.

His bill set aside $150 million to replace the old machines with new electronic touchscreens. These devices would produce a paper copy of the ballot – something that had been missing in Georgia for nearly two decades.

“The paper ballot enables voters to double-check their choices before casting their ballot and allows the counties to audit election results,” Fleming said.

The new machines were meant to increase trust in the system, but there are still lingering questions as to whether they will accomplish that goal.

House Bill 316 became law over the objection of dozens of Democrats, many of whom preferred hand-marked paper ballots, to cut down on the technology involved in the process.

In late July, Georgia awarded the contract for the new voting machines to Dominion Voting System. Rolling out the new equipment for all 159 counties would be the largest undertaking of its kind in the country.

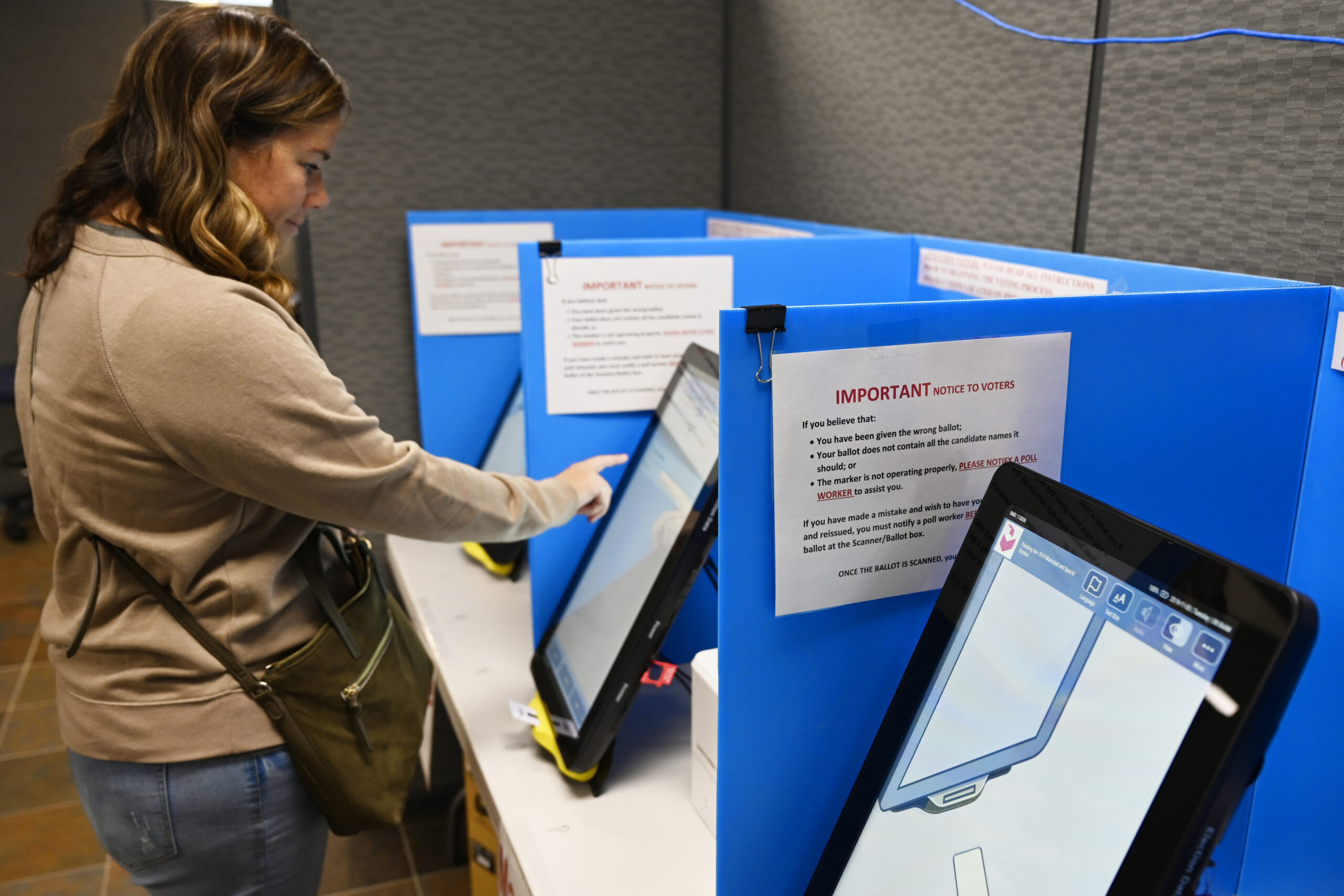

A handful of elections were used to test the new system last fall and early this year, but for the rest Georgia voters, public demonstrations were how they learned introduced to the new machines.

A Matter of Trust

On a Saturday morning in early February, Gwinnett County elections administrator Kristi Royston guided voters, step by step, through the process. Jim Sikes was among those who came to see the new setup.

“Well, I’m optimistic that they’re state of the art and that they’ll be secure,” said Sikes, who said he’s glad to see the state re-introducing a paper trail, considering the threats to elections from hackers.

“Under the circumstances, since 2016, I have a little more confidence that they’ll be less opportunities for the Russians to meddle with our elections,” he said.

For others, it wasn’t until their votes actually counted – during this month’s presidential primary – that they used the machines for the first time. Ralph Lewis, standing in the parking lot outside his polling place in DeKalb County, said the paper ballot increased his trust.

“I would think so because I saw that in my hand. I saw where it was cast, so I’m good, and I feel comfortable with it,” he said.

A University of Georgia poll conducted in February found that two-thirds of respondents were either confident or somewhat confident that their vote would be accurately recorded.

While many see the addition of a paper trail as a step in the right direction, others say it’s flawed.

That’s because, while voters get to review a plain-text readout of their selections before putting it through a scanner, the scanner actually reads a computerized code –a QR code– that humans can’t verify.

It’s something Beth Moore has heard concerns about. She’s a Democratic state lawmaker from Gwinnett County who voted against House Bill 316.

“The one question that routinely comes up, that I hear from voters, is that we want to know whether and how the Secretary of State’s office is going to conduct audits to make sure that the QR code is properly reading what the human eye can read,” she said.

Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger defends the system. He said QR codes are used everywhere and are dependable. He reached into his pocket and pulled out his phone, showing the electronic boarding pass from his last Delta flight.

“And right in the center, there is a QR code. And really, if it’s good enough for TSA, it’s good enough for the Department of Homeland Security,” he said. “And people need to understand that our voting systems have been tested.”

Raffensperger said those tests and spot checks of the ballots after an election can help ensure the QR codes are being produced correctly.

But as for a hand-recount in a close race? That may only happen as a result of a court order.

.’Is Newer Better?

The Secretary of State’s office argues that new machines with their more modern operating systems are safer.

But warnings from analysts that no system is 100 percent safe leave voters like Gil Roberson still feel a bit skeptical.

“It appears to be…to have more integrity than the other ones, but I don’t know. There’s still ways it could be faulty,” Roberson said.

On March 24, as the final votes in the presidential primary are cast, and results are reported, Georgia voters’ trust in the new system will get its first big test.

WABE’s coverage of Georgia’s new voting system is made possible through a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network.