Rahul Bali contributed audio to this report.

A former Georgia election worker in gripping testimony Tuesday told the House Jan. 6 committee about the onslaught of threats that she and her family received after former President Trump and his allies falsely accused her and her mother of pulling fraudulent ballots from a suitcase.

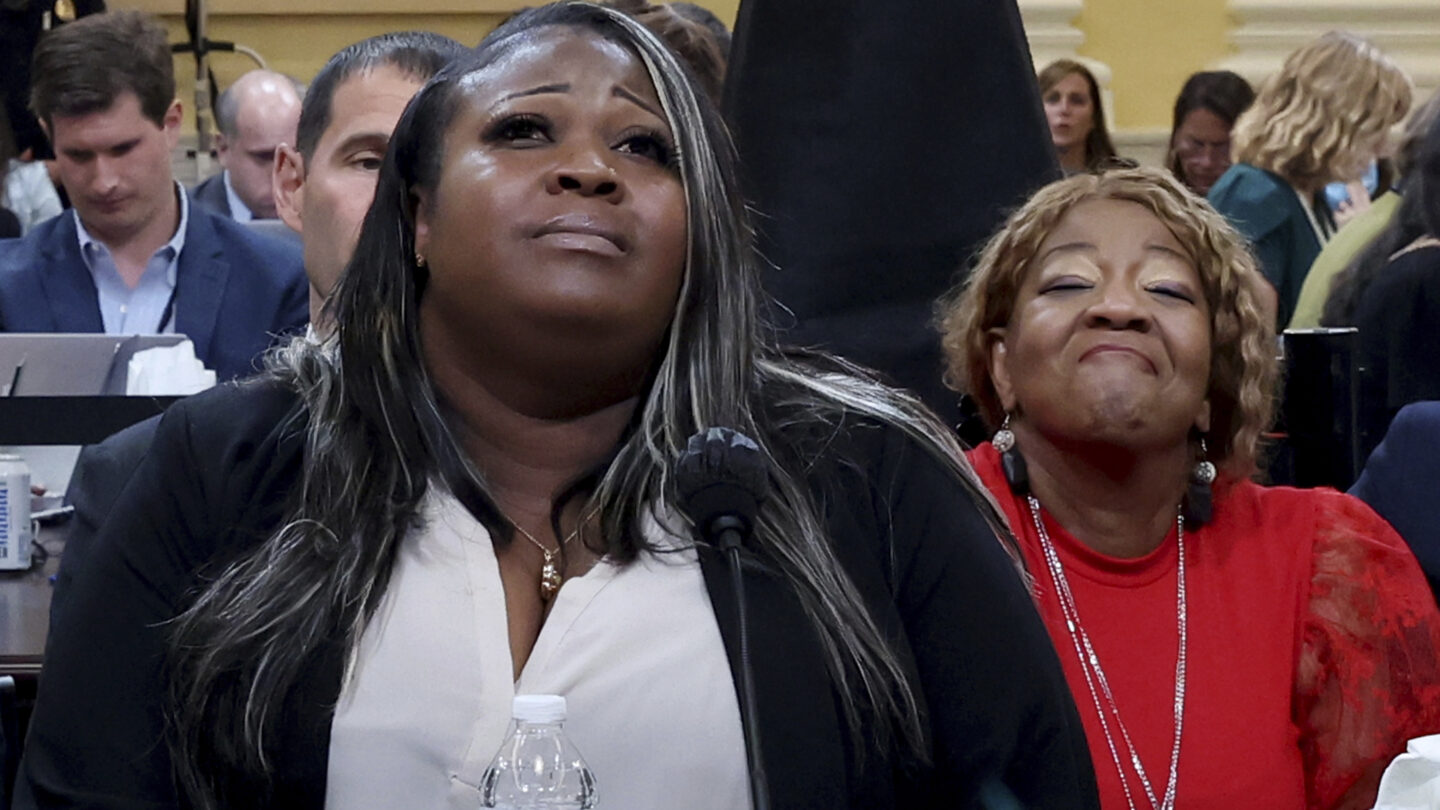

Wandrea “Shaye” Moss told lawmakers her life was upended when Trump and his allies latched onto surveillance footage from November 2020 to accuse her and her mother, Ruby Freeman, of committing voter fraud, allegations that were quickly debunked.

Moss, who is Black, said she received messages “wishing death upon me. Telling me that I’ll be in jail with my mother. And saying things like, ‘Be glad it’s 2020 and not 1920.'”

“A lot of them were racist,” Moss said. “A lot of them were just hateful.”

The committee also played testimony from Freeman, who sat behind Moss in the hearing room, showing support for her daughter and at one point passing over a box of tissues as lawmakers heard about their shattering ordeal.

“There is nowhere I feel safe. Nowhere,” Freeman told the committee in the prerecorded video. “Do you know how it feels to have the president of the United States target you? The president of the United States is supposed to represent every American, not to target one.”

“But he targeted me,” she added.

The emotional testimony from mother and daughter was just the latest attempt by the Jan. 6 panel to show how lies perpetrated by Trump and his allies about a stolen election turned into real-life violence and intimidation against the caretakers of American democracy: state and local election officials and workers.

The barrage of threats against the two county workers mounted after Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani played surveillance footage of them counting ballots in a Georgia Senate committee hearing on Dec. 10, 2021. Giuliani said the footage showed the women “surreptitiously passing around USB ports as if they are vials of heroine or cocaine.” What they were actually passing, Moss told the committee, was a ginger mint.

Giuliani and Trump allies kept repeating the false conspiracy theory that Moss and Freeman, along with other election workers in key battleground states, were packing ballots into suitcases. The claim was disproven by several Georgia election officials, who investigated and found the footage showed regular ballot containers used in Fulton County.

But it was too late. Conservative networks like One America News Network seized on the false claim and it began to spread with the help of Trump himself. Moss and Freeman eventually filed a defamation lawsuit against the network and Giuliani last December. The case against OAN has since been dismissed with a settlement.

Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., who led Thursday’s hearing, noted that Trump mentioned Freeman’s name 18 times in a call with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. At one point Trump called Freeman a “professional vote scammer and hustler.”

“This has affected my life in a major way. In every way. All because of lies. All for me doing my job. The same thing I’ve been doing forever,” said Moss, who had been an election official for 10 years.

With so many threats swirling, the FBI urged Freeman to leave her house ahead of Jan. 6 for safety reasons. She testified that she wasn’t able to return for two months and felt homeless.

“The point is this: Donald Trump didn’t care about the threats of violence,” Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., the vice chair of the committee, said in her opening remarks Tuesday. “He did not condemn them, he made no effort to stop them; he went forward with his fake allegations anyway.”

Raffensperger, Georgia’s top election official, and his deputy, Gabe Sterling, also testified about the relentless attacks they and their colleagues faced as Trump falsely claimed widespread voter fraud in Georgia.

Raffensperger and his wife were victims of organized harassment — commonly known as doxxing. His wife, he said, received “disgusting” text messages that were sexual in nature, and supporters of the president’s election claims broke into the home of Raffensperger’s daughter-in-law, where she was staying with her children.

Sterling recalled the moment in December of 2020 that pushed him to speak out. It was a tweet about a staffer for Dominion voting machines — the focal point of other Trump-promoted conspiracies about voter fraud — that said “you committed treason. May god have mercy on your soul.” It included a slowly twisting GIF of a noose.

“And for lack of a better word, I lost it,” Sterling told the committee. “I just got irate.”

That day Sterling gave an impassioned plea at a press conference pleading with Trump to condemn the threats against election workers. “This has to stop,” he said.