Opioid Crisis Forces Physicians To Focus On Alternative Pain Treatments

The opioid epidemic has forced doctors to think about alternative ways to help their patients manage pain.

Toby Talbot / Associated Press file

Dr. Anne Marie McKenzie-Brown is familiar with pain. Pain of varying degrees, stages, perceptions, types and sources.

“All of my patients have chronic pain, some have muscular skeleton pain, some have nerve pain,” says the director of the Emory Pain Center, an outpatient clinic located at Emory University Hospital Midtown.

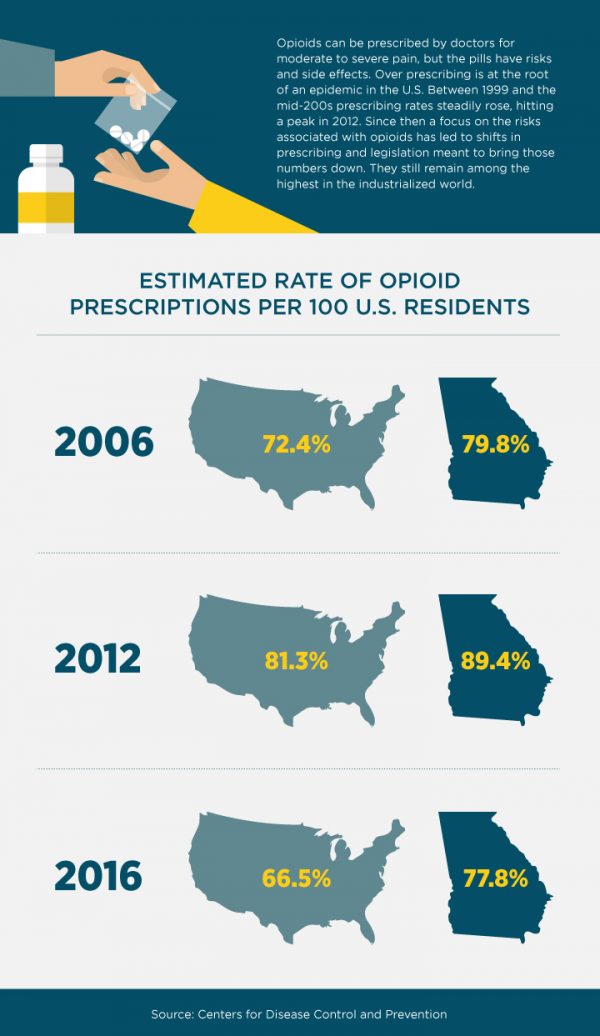

And then there is the dark side of pain management— opioid addiction. More than 53,000 Americans died from opioid abuse in 2016, according to the CDC.

Such staggering numbers have McKenzie-Brown and many of her colleagues studying new ways to manage pain. This past year, she sat on a national expert committee established by the Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in Washington, D.C.

The committee published a report about alternative paths to treating pain, including medication and non-medication approaches.

“We should take a step back and consider multiple ways to treat pain,” McKenzie-Brown says, “and not exclusively refer to opioids as pain medication.”

Alternative treatment options range from non-opioid pain medications, like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, to injections and interventions, like spinal cord stimulation; physical therapy; increased use of chiropractors; acupuncture; weight loss; even meditation or natural remedies.

The herb turmeric, for example, is known to have anti-inflammatory properties. “Some of my patients have used it for pain,” McKenzie-Brown said.

The new approach to pain treatment begins with a thorough assessment of patients, and a self-assessment by doctors.

“I have changed the way I look at treating pain from the early ’90s, when I started practicing, to now,” she said.

Shift In Approach To Pain

The 1990s marked a paradigm shift in how American medicine approached pain, as multiple groups advocated for stronger efforts to help people dealing with chronic pain. Doctors began prescribing opioids more freely and comfortably, and patients demanded them more aggressively.

Today, with the opioid epidemic in full swing, doctors are required to assess every pain patient for multiple treatment options. One of the few good things coming out of the opioid crisis, says McKenzie-Brown, is heightened public awareness.

“It’s become much easier for me as a physician to have the discussion with patients about the risks of opioids, because most people have heard of it,” she said.

Hilary Gray is all for a more natural approach to pain treatment. Gray, 60, works for an interior designer in Atlanta. She’s been suffering from chronic back pain for 20 years, after damaging several discs in a fall. She also has arthritis and some pinched nerves. “My doctor tells me, I’m a spinal train wreck,” she says with a dry smile.

Early in her pain journey, she took muscle relaxers, and received steroid epidurals. One of her orthopedists also laid out the option to use opioids for pain management. But Gray had taken opioids before and didn’t like how the drugs made her feel.

A few years ago, when she suffered a chemical burn, doctors prescribed OxyContin, a long acting and widely popular opioid.

“It was a very strange experience,” she remembers: “I’m a bit of a control freak, so it wasn’t for me.”

Today, Gray relies heavily on weekly visits to her chiropractor. She does physical therapy, yoga and stretching, and is considering acupuncture.

The alternative approaches take time and commitment. She gets up early every morning to do her exercise. She says she’s also lucky to have an employer who allows her to work flexible hours in order to fit in visits to the chiropractor.

“There’s no quick fix for chronic pain,” says Gray. “If people think they can just take a pill and the pain is going away, they are very optimistic.”

Doctor Looks To Holistic Options

While a strong focus on diversified and more holistic approaches to pain treatment may be relatively new in the United States, it has long been a common route to pain treatment in Europe.

It’s an approach that Dr. Carmen Klass tries to integrate into her practice.

“In oncology, we have always used alternative treatments,” says the German-born cancer specialist, who works in the Marietta office of Northwest Georgia Oncology Centers, a large outpatient cancer clinic.

“We use pain block injections. We use anti-depressants to modulate pain perception. We use pain medications that are not opioid based, and we use relaxation techniques, as well as acupuncture,” says Klass, who completed medical school in Germany and came to the U.S. on a post-doc fellowship in 1996.

She adds, though, that in oncology, opioids are an important and valuable treatment option, especially for advanced and late stage cancer patients.

While Germany, and most of Europe, also struggles with rising numbers of people abusing prescription medication, the problem is mostly with sedatives and tranquilizers, not opioids.

“I think it’s because there’s a huge stigma involved with the use of opioids,” Klass said.

A stigma that used to exist in the U.S. as well, but changed with the shift in pain treatment in the mid-1990s.

“When I prescribed narcotics in Germany, patients would always assume they were terminally ill,” she said. “Because, why else would I give them morphine?”

Klass thinks that job security may be another reason why more Europeans than Americans resort to non-medication, and time-consuming pain treatment. In the U.S., people only get a limited number of paid sick days. Most Europeans are protected not only for the duration of their acute illness, but also for rehabilitation.

The idea is that if people take time to get well, “they’re able to fully participate in the workforce,” says Klass. “And I think that’s a pivotal point.”

She often sees in her own practice, much to her regret, “that patients barely get time off to come to chemotherapy, let alone something as frivolous as physical therapy.”

It’s an argument that the national committee on alternative pain treatments might consider. Also, as committee member McKenzie-Brown points out: There is no one-size-fits-all option for pain treatment.

“Every patient, and every patient’s pain, is different,” she says. One thing is clear, though: “Opioids are not the first line therapy for chronic pain.”