As the human toll of the coronavirus continues to mount, so does the cost that comes with living during a pandemic.

Cloth and disposable surgical masks have become staples of pandemic life as many stores, restaurants and businesses require staff and customers to wear them. And many school districts around the country still have mask mandates in place.

At-home rapid tests have also become familiar as the surge of coronavirus cases over the new year caused a frenzy as millions of Americans rushed to get their hands on one. Some school districts also require negative tests before students return to campus.

For the most part, people have had to cover these expenses up front.

And while it might be a small price to pay for some, others are burning through their savings or choosing between paying bills or buying masks just to stay safe.

Counting the costs of disposable masks

Jerri Dodge, 63, retired early in the pandemic after working as a business consultant and retail worker in Ypsilanti, MI.

“I have two risk factors and fairly severe health issues,” Dodge said. “I needed to protect myself.”

Part of that protection for Dodge includes masks — she doesn’t leave her house without them.

“I am wearing double KN95s, I couldn’t afford the N95s,” she said.

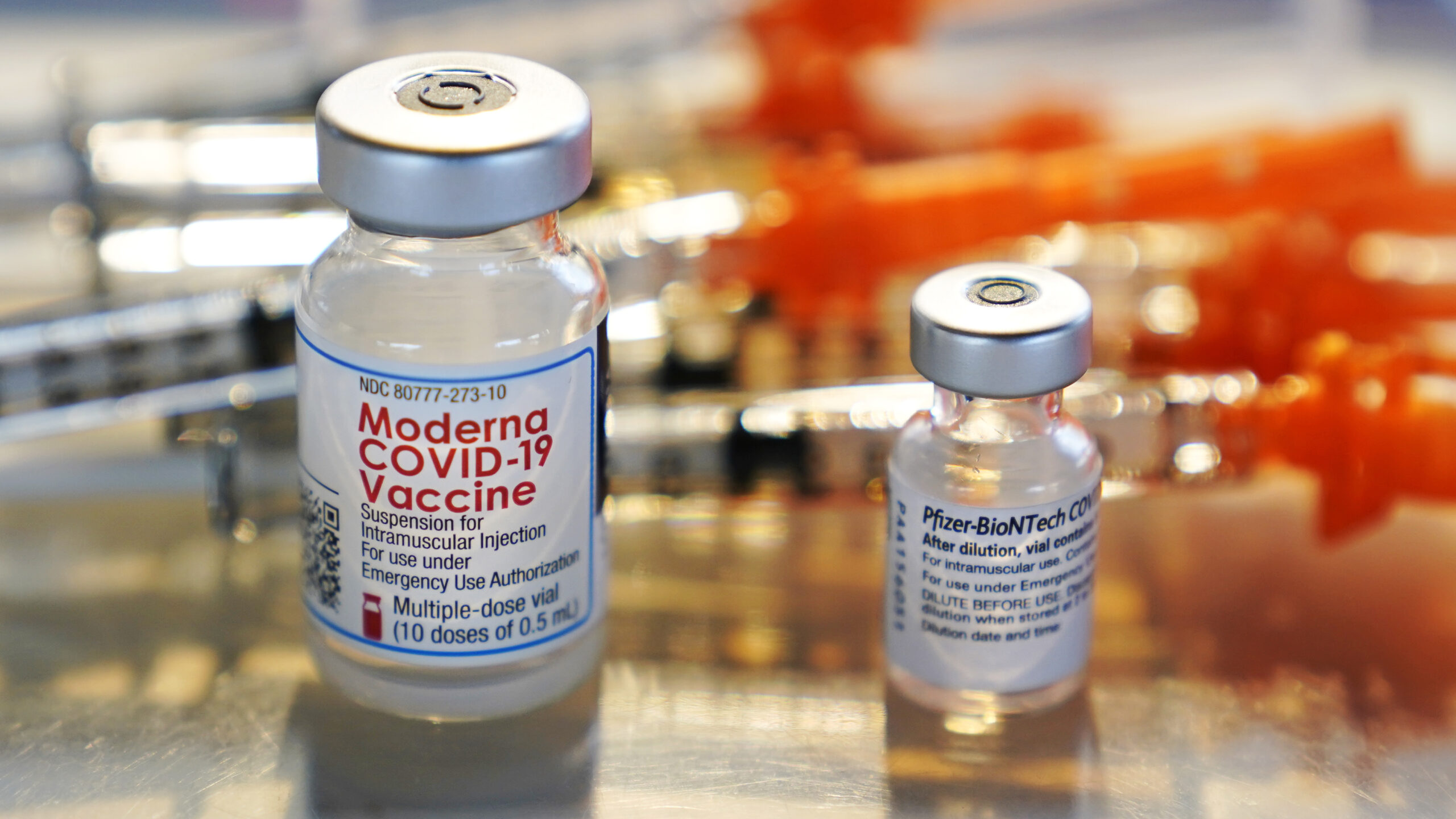

According to the CDC, the “highest level of protection” comes from respirators that are approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, such as N95 respirators. A box of 20 N95s on Amazon costs about $35, or roughly $2 a mask. KN95 masks are cheaper, ranging around $1 each.

It all adds up, said Dodge. Nowadays, she is cutting back on laundry costs by sticking to sweatpants, and spends more time searching for affordable food. She is still struggling to make ends meet.

“I put off my electric bill, which is outrageous this time, to purchase the KN95s,” she said. “I’m waiting for a shut-off notice before I get in touch with them and ask them to put me in a year-round budget.”

The U.S. job market showed gains through the end of 2021 and into January, despite the winter wave of coronavirus infections, but employment is still down 2.9 million jobs since the beginning of pandemic. Even as more people return to work or begin job hunting again, there are still many like Dodge.

“A lot of people came into the pandemic with really slim margins of savings and very little or maybe even negative wealth,” said Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution. She studies household spending and savings decisions.

“For those folks, putting even a little bit of pressure on their financial situation by adding some extra tax [like regularly purchasing masks] that they have to pay to make it through living in the midst of a pandemic is going to make their lives hard.”

The ‘time tax’ isn’t equal

It isn’t just a financial tax, either. Edelberg says there’s a time tax too: the time it takes to look for masks or wait in line for a free test.

Kisha Moore, 40, knows this time tax all too well. She runs a wholesale business from home, and is a single mother to six children.

“I have three kids that are going to school physically right now,” she said. “And then the two younger ones are virtual and homeschool.”

Despite all being vaccinated and boosted, COVID “spread like wildfire” through Moore’s house once her children went back to school in their North Carolina district.

“We were trying to test them out of quarantine and isolation, [but] I couldn’t find enough tests,” Moore said.

She checked pharmacies, searched shelves at Walmart and Target, looking everywhere until she was able to find rapid tests. She bought 10 tests for almost $300 out of pocket.

With six mouths to feed, and needing to buy cleaning supplies and disposable surgical masks in bulk, it hit her budget hard.

“So it’s just like, when I don’t have [the money], it goes on my [credit] card,” Moore said.

People with more money can avoid this time tax. Edelberg points to mobile COVID testing services that come to homes and businesses – for a hefty fee.

“There are people who maybe prefer to be spending their time doing something else, but at least have the time to be able to comb through the neighborhood list servs to figure out which store just got masks,” Edelberg said.

“Then there are the people who have neither time nor money, and that’s who we should worry about the most.”

‘What will it look like in 6 months?’

The Biden Administration is distributing 400 million free N95 masks as part of its effort to combat COVID-19. They are now available for pick up in certain pharmacies and health centers around the country; each person is allowed three masks, as supplies last. Four free at-home COVID tests can be ordered through a form on the U.S. Postal Service website.

“It is certainly a step in the right direction,” Edelberg said. But she worries whether the limited supply is too little, too late.

“Getting a couple of masks, that’s a good thing, but that doesn’t meet them where their lives are,” she said.

Those three N95s per person won’t last long in Moore’s house.

“We could go through a box of masks in four to five school days,” she said, especially since her children are going to in-person school. Moore is also keenly aware of other parents in her community who are struggling more than she is and can’t afford masks at all, so she also sends her kids to school with extra masks in sandwich bags.

Moore has tightened her budget as much as she can, by eliminating extra entertainment, planning her groceries “down to the dollar” and buying cheap masks in bulk. Her bills are only getting higher, and Moore worries about the future.

“What is it going to look like in six to eight months?” she said. “I’m just trying to prepare as best as I can. I’m hoping it is going to lighten up and we can really start to recover.”

Edelberg said the aggregate economy is doing pretty well. Americans, as a whole, were able to save more during the pandemic. But those savings were concentrated among wealthier households. Lower income households did save more during the pandemic too, but those savings didn’t translate to a larger cash buffer.

“It’s not that I’m worried about the economy in aggregate,” Edelberg said. “I’m worried about who the fiscal support didn’t reach, and I’m worried about who the labor market recovery is not reaching.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))