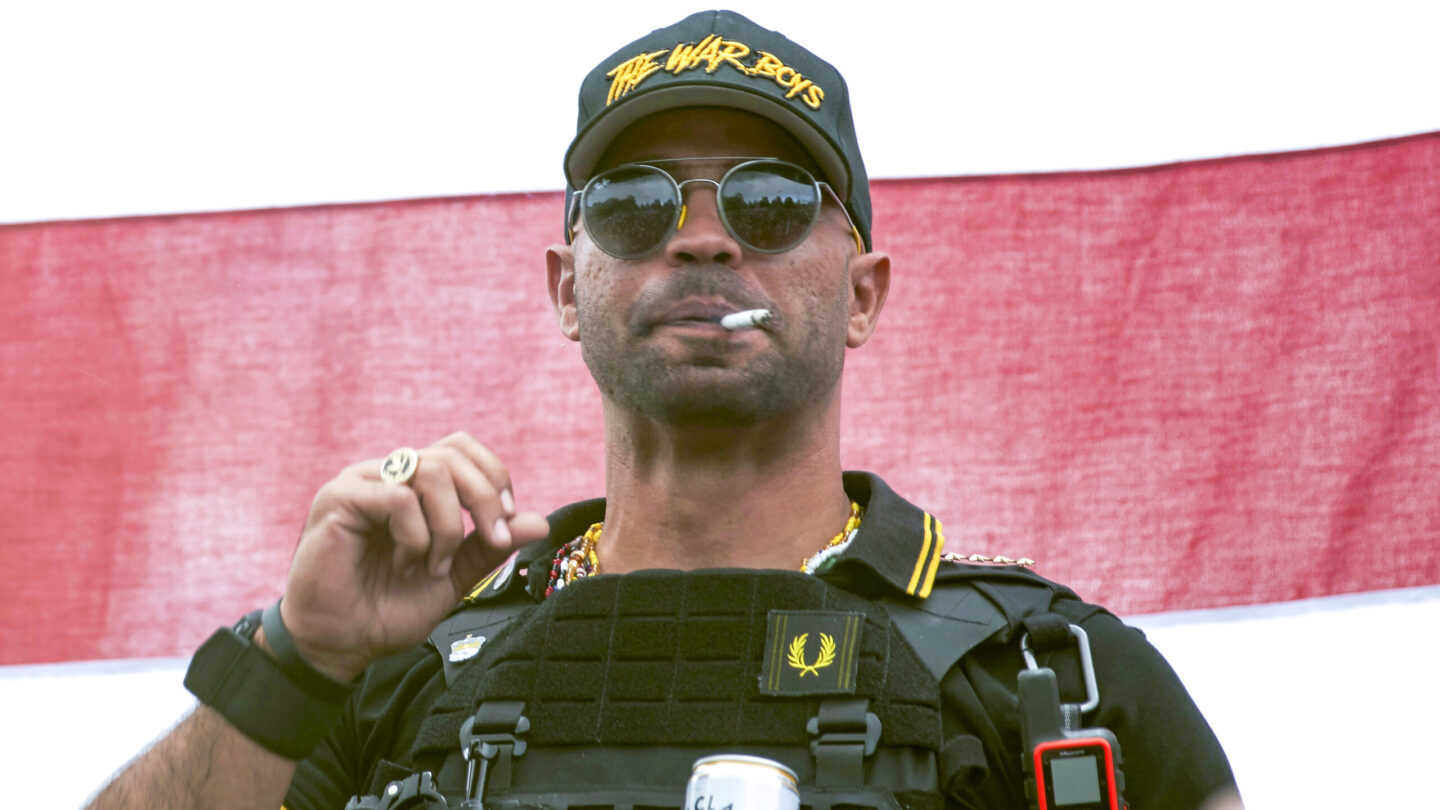

As members of the Proud Boys extremist group stormed past police lines and swarmed the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, their leader cheered them on from afar, prosecutors say. “Do what must be done,” Enrique Tarrio wrote on social media. “So what do we do now?” someone asked later that day in a Proud Boys encrypted group chat.

“Do it again,” Tarrio responded.

Almost two years later, Tarrio’s words are at the center of the Justice Department’s seditious conspiracy case against the former Proud Boys national chairman. Prosecutors in his trial in Washington are trying to build on their recent courtroom victory against leaders of another far-right extremist group, the Oath Keepers.

Tarrio, who led the neofacist group as it became a force in mainstream Republican circles, is perhaps the highest-profile defendant yet to stand trial for charges stemming from the insurrection. Tarrio and four lieutenants face up to 20 years in prison if convicted of seditious conspiracy. Jury selection is underway and opening statements could begin later this week.

The trial comes at a pivotal time in the Justice Department’s wide-ranging Jan. 6 investigation. Key aspects are now overseen by special counsel Jack Smith, who was appointed by Attorney General Merrick Garland. Smith has issued a number of subpoenas in recent weeks to state election officials, seeking their communications with Donald Trump and others involved the then-president’s efforts to overturn his 2020 loss to Democrat Joe Biden.

The House committee that investigated the Capitol riot urged the department to bring criminal charges against Trump. While the referrals carry no legal weight, the recommendation could increase public pressure on the department to prosecute Trump, who called on supporters to “fight like hell” before the siege that halted congressional certification of Biden’s victory.

The department is buoyed by the recent sedition guilty plea of a close Tarrio associate, who could provide potentially damning testimony under a cooperation deal, and the convictions in November of Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes and the head of the anti-government group’s Florida chapter.

In Tarrio’s case, prosecutors are hoping to convince jurors that they should convict him of overseeing a violent plot to stop the transfer of presidential power even though he was not in Washington on Jan. 6. Tarrio had been arrested in a separate case days earlier.

Tarrio’s lawyers say he did not instruct or encourage anyone to go into the Capitol. Their defense may focus on communications they say show Tarrio was informing law enforcement in the run-up to Jan. 6 of the Proud Boys’ plans to protest the results of the election and party that night with — as they wrote in court papers — “plenty of beer and babes.”

The trial will put a spotlight on the Proud Boys, which remains an influential force in right-wing circles even with many of its top leaders behind bars. Trump energized the group and elevated its profile when he infamously told the Proud Boys to “ stand back and stand by ” during a 2020 debate with Biden.

While there were signs the Oath Keepers were in disarray even before Rhodes’ conviction, the Proud Boys have proved more resilient.

Proud Boys members have reveled in street violence since the group’s inception, typically clashing with anti-fascist activists at rallies. Tarrio initially called on members to stand down after Jan. 6 and refrain from holding public events. Instead, local Proud Boys chapters found new targets to menace.

Proud Boys have recently disrupted story telling sessions by drag performers and other LGBTQ events. Members have showed up at school board meetings and other local government forums, often to protest COVID-19 masking requirements. They joined anti-abortion protests surrounding the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling overturning Roe vs. Wade last year.

The autonomy afforded local Proud Boys chapters has helped the group weather the loss of its leaders better than the Oath Keepers have, said Jon Lewis, a research fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism. Lewis, who has written about the Proud Boys’ violent evolution, said securing a conviction of Tarrio and his lieutenants would not cripple the group or prevent local chapters from organizing.

Tarrio’s co-defendants are Ethan Nordean of Auburn, Washington, who was a Proud Boys chapter president; Joseph Biggs of Ormond Beach, Florida, a self-described Proud Boys organizer; Zachary Rehl, who president of the Proud Boys chapter in Philadelphia; and Dominic Pezzola, a Proud Boy member from Rochester, New York.

The jury’s mixed verdict in the Oath Keepers case shows the challenge prosecutors face in proving the rarely used seditious conspiracy charge. While Rhodes and Oath Keeper Kelly Meggs were found guilty of sedition, three co-defendants were acquitted of the charge. All five were convicted of serious felonies, but it was the first time jurors had acquitted any Jan. 6 defendants of a crime.

It came after defense lawyers spent weeks hammering prosecutors for their lack of evidence that the Oath Keepers had a specific plan to attack the Capitol before Jan. 6.

In the Proud Boys case, however, prosecutors say they have communications showing that members did discuss storming the Capitol before Jan. 6.

A week before the riot, prosecutors say Tarrio received a document with the title “1776 Returns” from an acquaintance that laid out plans for occupying certain government buildings in Washington on Jan. 6. The document made no mention of the Capitol itself. But days later, Proud Boys were focusing their attention there, prosecutors allege.

“Time to stack those bodies in front of Capitol Hill,” one extremist wrote in a secured chat. “What would they do (if) 1 million patriots stormed and took the capital building. Shoot into the crowd? I think not,” wrote another member. “They would do nothing because they can do nothing,” someone responded.

Days before the riot, someone suggested in a voice note to the Proud Boys group that the “main operating theater” should be in front of the Capitol. “I didn’t hear this voice note until now, you want to storm the Capitol,” Tarrio said later in the same chat.

Tarrio was arrested on Jan. 4, 2021, after he arrived in Washington. He was charged with burning a Black Lives Matter banner from a historic Black church and possessing high-capacity firearm magazines. Law enforcement later said Tarrio was picked up in part to help quell potential violence after earlier demonstrations in Washington supporting Trump’s baseless claims of fraud led to stabbings and arrests. The day before the riot, a judge ordered Tarrio to stay out of Washington.

But instead of leaving right away, prosecutors say Tarrio met for about 30 minutes with Rhodes and others in an underground parking garage. Authorities have said someone at the meeting referenced the Capitol; little else is publicly known about what was discussed.

Even after leaving Washington, Tarrio continued to exercise command over the Proud Boys on the ground on Jan. 6, prosecutors say.

His lieutenants were part of the first wave of rioters to push onto the Capitol grounds and charge past police barricades toward the building, according to prosecutors. Pezzola used a riot shield he stole from a Capitol Police officer to break a window, allowing the first rioters to enter the building, prosecutors allege.

“Don’t (expletive) leave,” Tarrio wrote on social media after several Proud Boys were already inside. Moments later he wrote: “Proud Of My Boys and my country.”