Ralph Puckett Jr., a retired Army colonel awarded the Medal of Honor seven decades after he was wounded leading a company of outnumbered Army Rangers in battle during the Korean War, has died at age 97.

Puckett died peacefully Monday at his home in Columbus, Georgia, according to the Striffler-Hamby Mortuary, which is handling funeral arrangements.

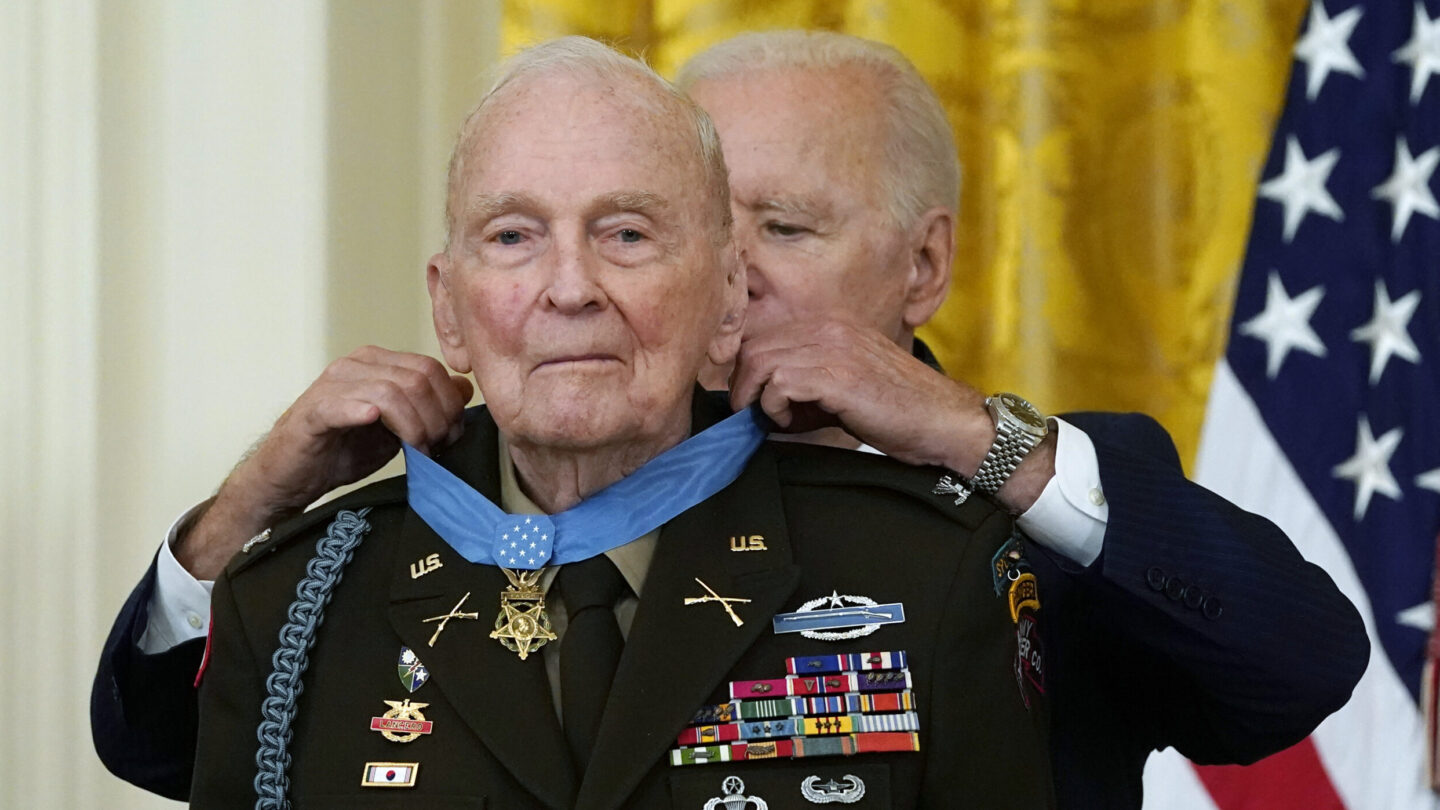

President Joe Biden lauded Puckett for his “extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty” while presenting the retired colonel with the nation’s highest military honor at the White House in 2021. Biden noted the award was “more than 70 years overdue.”

“He’s always believed that all that mattered to be a Ranger was if you had the guts and the brains,” Biden said.

Puckett was a newly commissioned Army officer when he volunteered for the 8th Army Ranger Company that was formed soon after the Korean War began in 1950. Despite his inexperience, Puckett ended up being chosen as the unit’s commander. He had less than six weeks to train his soldiers before they joined the fight.

“I said to myself: ‘Dear God, please don’t let me get a bunch of good guys killed,'” Puckett told the Ledger-Enquirer of Columbus in a 2014 interview.

Over two days in November 1950, Puckett led his roughly 50 Rangers in securing a strategically important hill near Unsan. Puckett sprinted across the open area to draw fire so that Rangers could find and destroy enemy machine-gunners. Though badly outnumbered, Puckett’s troops repelled multiple counterattacks from a Chinese battalion of an estimated 500 soldiers before being overrun.

Puckett suffered serious wounds to his feet, backside and left arm after two mortar rounds landed in his foxhole. He ordered his men to leave him behind, but they refused.

Puckett was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest U.S. military honor, in 1951. It was upgraded to the Medal of Honor decades later following a policy change that lifted a requirement that such awards be made within five years of valorous acts.

During the White House medal presentation, Biden said that Puckett’s first reaction to receiving the honor had been: “Why all the fuss? Can’t they just mail it to me?”

Despite his injuries in Korea, Puckett refused a medical discharge from the Army and spent another 20 years in uniform before retiring in 1971. He was awarded a second Distinguished Service Cross in 1967 for dashing through a hail of shrapnel to rescue two wounded soldiers in Vietnam, where Puckett led an airborne infantry battalion.

Puckett’s military honors also included two Silver Stars, three Legions of Merit, two Bronze Stars and five Purple Hearts.

“He feared no man, he feared no situation and he feared no enemy,” retired Gen. Jay Hendrick, who served as the top general of U.S. Army Forces Command from 1999 to 2001, said in the Army’s online biography of Puckett.

Born in Tifton, Georgia, on Dec. 8, 1926, Puckett graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and received his commission as an infantry officer in 1949.

After retiring from the Army, Puckett served as national programs coordinator of Outward Bound, Inc., and later started a leadership and teamwork development program called Discovery, Inc. He remained an active supporter of the 75th Ranger Regiment stationed at Fort Moore near his Columbus home.

Puckett told the Columbus newspaper he learned one of his most important life lessons on his first day at West Point, when a senior cadet told him that one of the few acceptable answers he could give to any question would be: “No excuse, sir.”

“It was ingrained on my thinking that I have no excuse at any time I do not meet the standards that I’m supposed to meet,” Puckett said.