It’s no secret that Atlanta has been susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS, HIV and others have put Atlanta on the map in somewhat of a negative way.

In February, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution published reporting about how a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report last year, ranked Georgia fifth for rates of HIV diagnoses in 2015. The high rate of sexually transmitted diseases even has some people unaffectionately using the term “AIDSlanta” on Twitter.

Both of our schools — Tucker Middle and High Schools — offer sex education. But our experiences weren’t inclusive of LGBTQ teens or HIV prevention.

Amira: At Tucker Middle School, last year I had a health teacher who only touched on sex education. He did not go in depth, but when he talked about men and women being sexually active, classmates would make noises, like moaning. My classmates would laugh. My science teacher did talk about sex education. She explained the different parts of the body, along with reproduction and how it works. But she did not discuss preventing STDs or pregnancy.

Sex ed is important because teens make out and you don’t know if someone has herpes or other STDs. My friend from school told me last school year she often saw a couple — two teens from our school — making out outside during PE’s cardio day. Another one of my friends told me about their friend doing a live video, where someone in the chat section asked a question about the noise in the background before seeing a couple in the vlogger’s house. The person who was doing the live video simply laughed before making a sexual innuendo. So, teens my age need to know how to stay safe.

Billaé: At Tucker High School, students are required to take a health class (in their freshman year) for the duration of two semesters, covering a wide variety of topics. It may sound surprising to hear that my lesson regarding sexual health was very brief. Looking back, it literally feels like we spent maybe a week and a half talking about sex. Even though DeKalb County Schools implemented a new curriculum for comprehensive sex education in 2015, there was only one word I remember: A-B-S-T-I-N-E-N-C-E. Many people I knew had already had sex in middle school, so when the topic of abstinence came up, they did no more than laugh at the notion. It was a lesson that fell on deaf ears.

The disconnect between what we heard in sex education and what we see was something we wished to change. So, we conducted multiple interviews, trying to find some insight into the issue we were facing.

Inclusive Or Comprehensive Sex Ed?

Eighteen-year-old Carolyn Friedman just graduated from North Springs Charter School of Arts and Sciences and has worked as an intern for the director of education at Planned Parenthood Southeast. She took sex ed online during her freshman year of high school — and estimates a “good percentage of my class” did the same — but said she “learned basically nothing.”

“Georgia sex ed on its own is not incredibly comprehensive,” she said. “For me personally, as a queer teen growing up in metro Atlanta, what that would have meant is that queer sex ed as well as the typical heterosexual education would have been enormously helpful.”

“You know, our only sources of information about sex and whatnot is from the internet. Sometimes information is good, sometimes it’s not, and so I think inclusive sex ed would have included information for queer teens, that wasn’t your typical heterosexual sex. Also, sex ed that isn’t just anatomy-based but that talks about communication and emotions and all the other stuff that comes with sex that people feel sometimes in school isn’t as important but is incredibly important.”

“Queer teens are often left out of the conversation especially in Georgia. People feel if you give teens information on sex then they’re going to have sex. And even worse than giving information on heterosexual sex is giving information on queer sex because that’s when everyone’s going to turn gay and start having sex with each other — and what are we going to do then — which is not the case, obviously.”

Friedman added: “It would have been really helpful for me to have had somewhat of an education. Schools overlook queer teens often, speaking from my experience.”

A 2015 study by the Public Religion Research Institute found only 12 percent of millennials surveyed say same-sex relationships were covered in their sex education class. “In a world where not a lot of people choose abstinence,” said Friedman, it’s important for sex ed to include information about ways people can avoid STIs and manage the “emotional consequences” of sex for LGBTQ teens as well as heterosexual teens. “It’s not just about preventing pregnancy,” she said.

Friedman said the lack of information for LGBTQ teens at school is nothing short of problematic. As a queer teen, she said she did not learn about how to prevent STIs at school and learned about it from her internship at Planned Parenthood.

“Coming in a year ago, I just didn’t know it. I had done research on the computer, like I need to get tested for x, x and y after I started having sex, but working at PP was nice on a personal level because I learned [how often] to get tested … and for what.”

Only 12 states in the U.S. “require discussion of sexual orientation” in their sex education curricula, according to a Guttmacher Institute review of sex ed in America. And only “8 states require that the program must provide instruction that is appropriate for a student’s cultural background and not be biased against any race, sex or ethnicity.”

Many states, like Georgia, leave it up to individual school districts. We talked to Michael Tenoschok, a program specialist with the Georgia Department of Education’s Health and Physical Education Division.

Tenoschok read material from the state board of education to us in our phone interview: “The local board of education shall develop and implement an accurate, comprehensive health and PE program that shall include information … related to, for example, alcohol and other drug use, disease prevention, environmental health, nutrition — and then it goes on to sex education, AIDS education, growth and development, safety, mental health, and then a list of a few other things in there. So, basically, it’s the local board of education that decides what is going to go into the local curriculum.”

[Related story: How Health Is Taught in Metro Atlanta]

“Before they put anything in related to sex education and HIV education,” Tenoschok said, “they have got to run the curriculum and any related materials, the textbooks, videotapes, brochures, guest speakers — anything that’s going to be used with students — all of that has to go in front of a local sex education review committee…”

We asked why our school may teach something different than other schools. “It’s really up to the local school system and the local schools … This is just to make sure what’s being taught is in line what being the values of the community.”

“There are regulations that each system has to go by … so you just don’t have a teacher taping something off of TV or bringing a DVD in from a store somewhere and putting it on without any prior approval. So the whole review process and the committee is there to make sure that whatever your teachers are teaching reflect the wants and the needs of the school system and the local community.”

Tenoschok also said parents can take a look at whatever gets approved and decide “if they want their children to be part of that class.” And they have the right to have their kids opt-out of the sex ed unit.

We wondered: Why doesn’t the Georgia Department of Education ask teens about their thoughts or wants in their planning around sex education? “The way the guidelines are set up for that committee, there are supposed to be at least one boy and one girl — a high school junior or senior — have to be on that review committee. And that review committee is supposed to be made up primarily of non-teaching parents. There are supposed to be kids involved in this whole process.”

The Department of Education representatives we spoke to said we should bring any concerns we have about about our particular school system/s to the local school board. Or, Tenoschok said, talk to the head of health and physical education for the schools.

“That’s the kind of avenue someone would take to try to get instruction changed in a particular county,” Tenoschok said.

In a state with such high HIV rates, we wondered how the Department of Education may address STI prevention without comprehensive or inclusive sex education. “Georgia is a local control state,” Tenoschok reiterated. “So it’s up to the individual counties to decide what to put in place to meet the individual needs of their kids. … We have in our [state] guidelines here that this information needs to be taught, but how it’s taught and what materials are used, that’s up to the local system.”

Gay-rights activists say a lack of comprehensive sex education can contribute to unsafe school environments.

Christian Zsilavetz oversees the Atlanta-based PRIDE School, which is tailored to LGBTQ students. Zsilavetz said curriculum change first needs to start with normalizing same-sex relationships across all subjects, not just sexual education.

“I think you can normalize the relationships 90 percent better if you actually acknowledge — for instance — when you go to history class, are you talking about LGBT people in history? I think it takes a village to make LGBT-inclusive sex ed happen.”

Even though many other schools may be hesitant to update their curriculum, pop culture is picking up the topic.

This summer Teen Vogue, aimed at those in their late teenage years, recently published “Six Things You Shouldn’t Assume About Queer Sex” and a factual story about anal sex, which covers everything from its appeal, communicating with a partner and using protection.

Despite how it may appear, this is an article that solely wishes to inspire a change in our education system as opposed to strictly condemning the ones present.

When the members of the VOX Media Cafe decided on the topic of the future of Atlanta, the only thoughts in our minds were: What types of changes do we want to see in our city? For Amira and I, this meant a change in the standards regarding sexual education.

From the statements we made above, we can only hope that you’ve seen the points we’ve illustrated. However, despite our stance on the issues, we invite you to make your own. Use this article (along with the other great ones in this issue) and deduce your own notions of what needs to be changed. If enough people see a problem, then there’s only a matter of time before they decide to fix it.

Tales Of Tucker: Why We Wanted To Tell This Story

Not only is hashtag “AIDS-lanta” insensitive, it’s also inexcusable for us as a city to not have a desire to change this. This can start with improving the current sexual education curriculum, which includes widening its scope. If one were to take a look at the standards students are held to in their health class, there would certainly be a few eyebrows raised.

Billaé is a 16-year-old rising junior at Tucker High School. She and Frank Ocean are probably long-lost siblings. Amira is a 13-year-old rising eighth-grader at Tucker Middle School. She is a chicken nugget connoisseur.

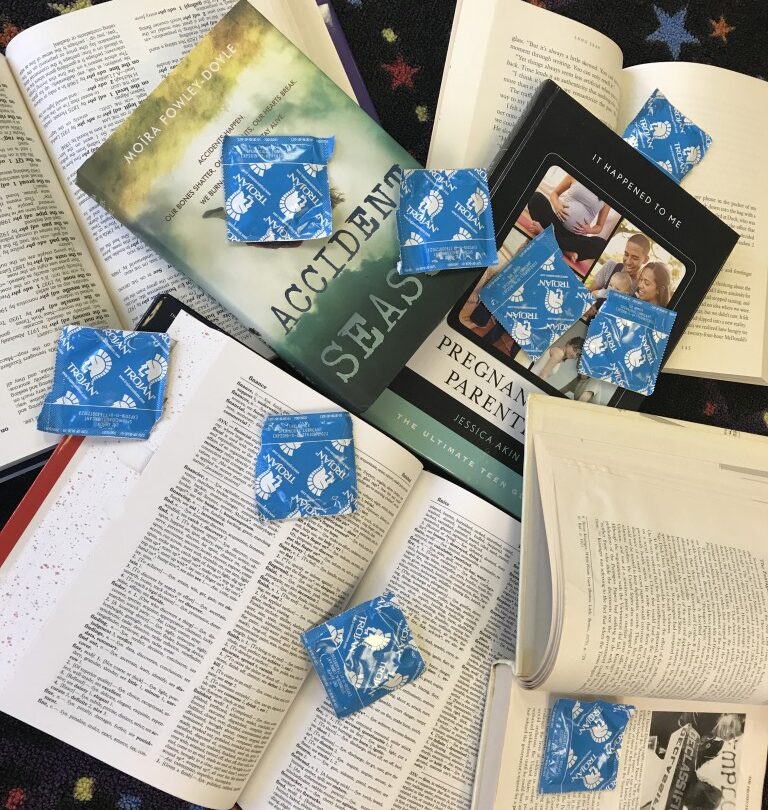

Photo illustration above by Billaé Blanding.

This story was published at VOXAtl.com, Atlanta’s home for uncensored teen publishing and self-expression. For more about the nonprofit VOX, visit www.voxatl.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))