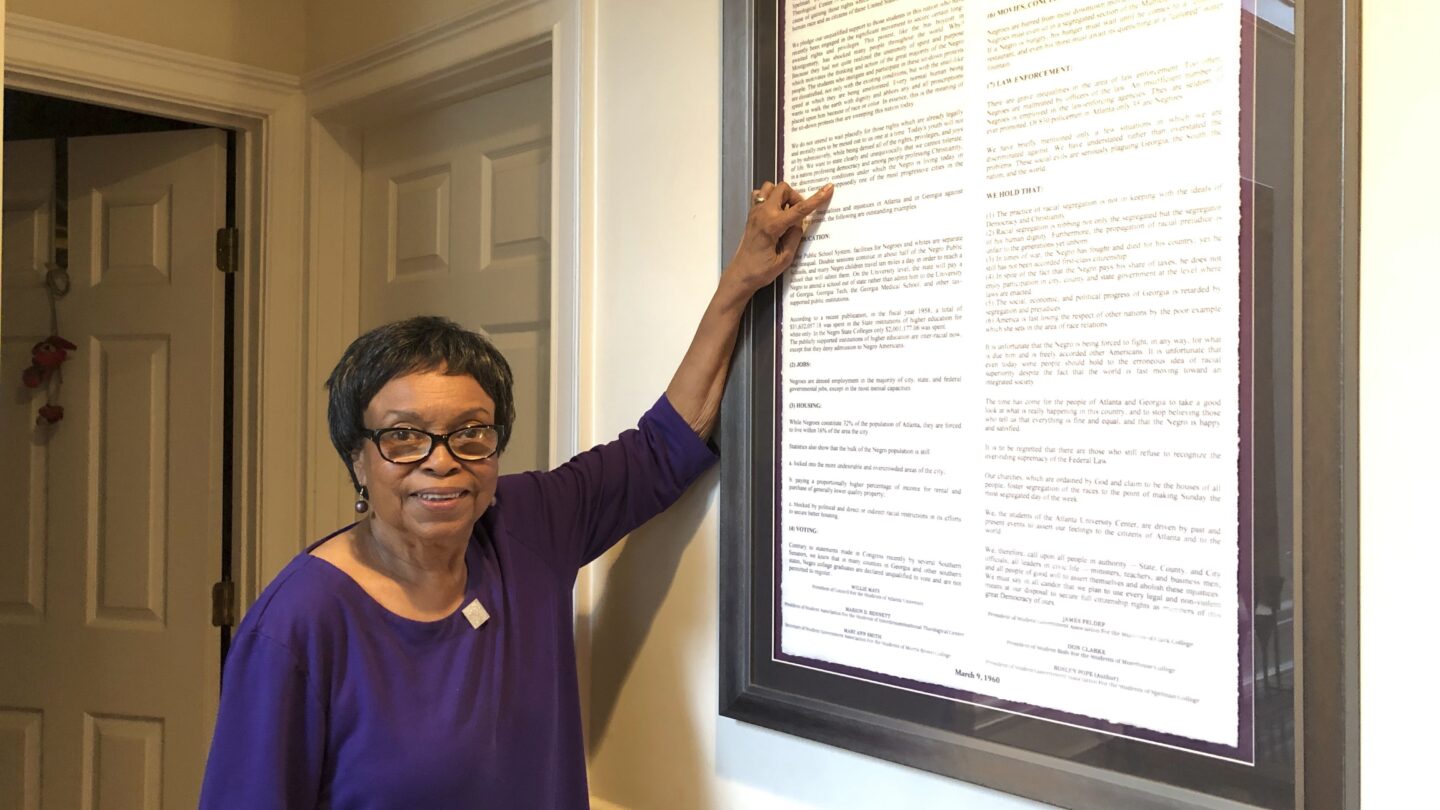

Roslyn Pope, a college professor and musician who wrote “An Appeal for Human Rights,” laying out the reasons for the Atlanta Student Movement against systemic racism in 1960, has died. She was 84.

Pope died Jan. 18 in Arlington, Texas, where she moved from Atlanta to be with her daughters after her health began to fail in 2021, according to her family’s obituary.

The document Pope wrote as a 21-year-old senior at Spelman College launched a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins by Black college students protesting discrimination not just in voting but in education, jobs, housing, hospitals, movies, concerts, restaurants and law enforcement.

“We do not intend to wait placidly for those rights, which are already legally and morally ours, to be meted out to us one at a time,” the Appeal declared. “We plan to use every legal and non-violent means at our disposal to secure full citizenship rights as members of this great Democracy of ours.”

Atlanta’s white-owned newspapers wouldn’t publish it, and Georgia’s segregationist leaders tried to dismiss it, saying it couldn’t possibly be the work of college students. But The New York Times ran it on a full page, as did other publications across the U.S. It was read into the Congressional Record as a testament to how segregation was stifling the ability of people to coexist with equality and dignity.

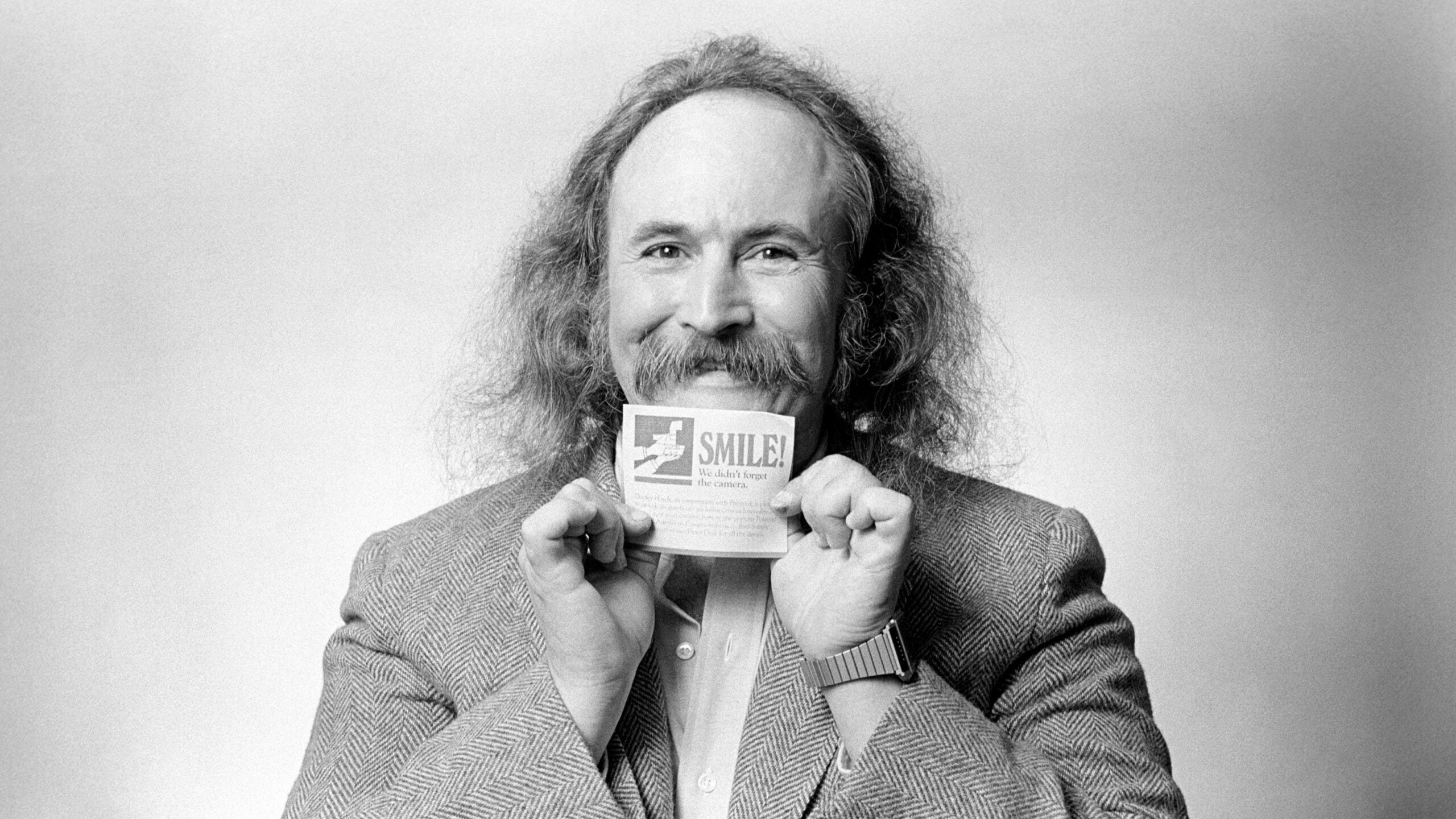

“She really kicked off our movement and made it acceptable,” Charles Black, who was a Morehouse College student when he joined Pope and others organizing the campaign, recalled Monday.

Pope showed that change doesn’t depend on “great men” like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and that a few committed people can make a real difference, Black said. “Because of her words, everybody understood what we were trying to do, and that’s why we had such broad, community-wide support.”

Born Oct. 29, 1938, in Atlanta, Pope was exceptional from an early age. She belonged to an all-Black Girl Scout troop and was sent as Georgia’s representative to a national camp in Cody, Wyoming, that no Black Scout had attended before.

“I was one little dark person among 50 white faces,” she recalled in an AP interview in 2020. “It became national news. Nobody in Atlanta could fathom that such a thing could happen.”

Pope was elected student body president at her segregated Booker T. Washington high school and at college. Her piano playing at Friendship Baptist Church led to a performance with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and later, a Merrill scholarship to study music during her junior year in Paris.

The experience was life-changing after growing up in a society where race laws restricted her every move, she told the AP.

In Paris, “there were no boundaries — no places I couldn’t go, no programs I couldn’t take advantage of, no limits to my existence. I could eat where I wanted — I couldn’t do that in Atlanta. It felt like shackles had been taken off me. It was just unbelievable.”

Along with movement co-founder Lonnie King, a Morehouse student who had been in the Navy, she felt suffocated after returning to the segregated South. “We just could not pretend that being treated as inferior was all right,” she said.

Pope said she was sharing her misery with future state lawmaker and NAACP chairman Julian Bond at an off-campus drugstore when King walked in waving a newspaper: Four Black students had been arrested at a sit-in the day before in Greensboro, North Carolina.

“It just clicked,” she said. “‘Why aren’t we doing that?’ we said to each other. And before the day was over, we decided to start a movement. We would no longer bear the mantle of inferiority.”

Working in secret, they recruited other students at Morehouse, Spelman, Clark and Morris Brown colleges, Atlanta University and the Interdenominational Theological Center. The six university presidents got wind of their efforts and tried to quash it. When the students refused, they were told to write up a clear explanation of what they hoped to accomplish.

King appointed Pope to a committee to draft the document, and after the young men let days pass without contributing, told her to “write the damn thing,” Black said.

And so Pope did, longhand. She and Bond then spent the night at the dining room table of Spelman professor Howard Zinn, who offered his typewriter. “Julian Bond was typing while I handed him the pages,” Pope said. “We were there all night because we didn’t have a lot of time.”

While the students’ campaign of civil disobedience would eventually break Atlanta’s stalemate over civil rights and hasten the end of racist Jim Crow laws and policies across the U.S., Pope remained a mostly private figure.

She earned a masters in English at Georgia State University and then a doctorate in humanities at Syracuse University, all while raising two daughters, Rhonda and Donna Walker, after a brief marriage to John W. Walker.

She later taught religious studies and led the music department at Penn State University, but said she faced a losing battle there against white prejudice, so she moved to Bishop College in Dallas. After that historically Black college closed, she taught literature and humanities at the University of Texas at Arlington. She later worked in advertising for 20 years at Southwestern Bell before retiring to Atlanta.

“She was a very quiet and unassuming person, not the kind of person you would expect to achieve that kind of status and leadership, necessarily, but she did,” said Black, who described Pope as a “sage.”

“The fact that she was able to put that document in the frame of human rights rather than civil rights was rather prophetic and very forward thinking. Civil rights can be voted in and out of existence, but human rights are inherent in our mere existence, and she recognized that early on,” he said.

Pope said she was thrilled in 2020 to share her experiences with students at Decatur High School as they researched the student movement and the related imprisonment of Martin Luther King for a Georgia Historical Society marker. The same students then campaigned to bring down a nearby Confederate monument.

The Appeal “is just as relevant now as it was when I wrote it,” she told them. “I’m glad that I could do something. It might have been a small contribution, but I contributed.”

The Friendship Baptist Church plans a Feb. 17 service in her memory, and a celebration of Pope’s contributions to racial equality will be held at Spelman College on March 9, Black said.