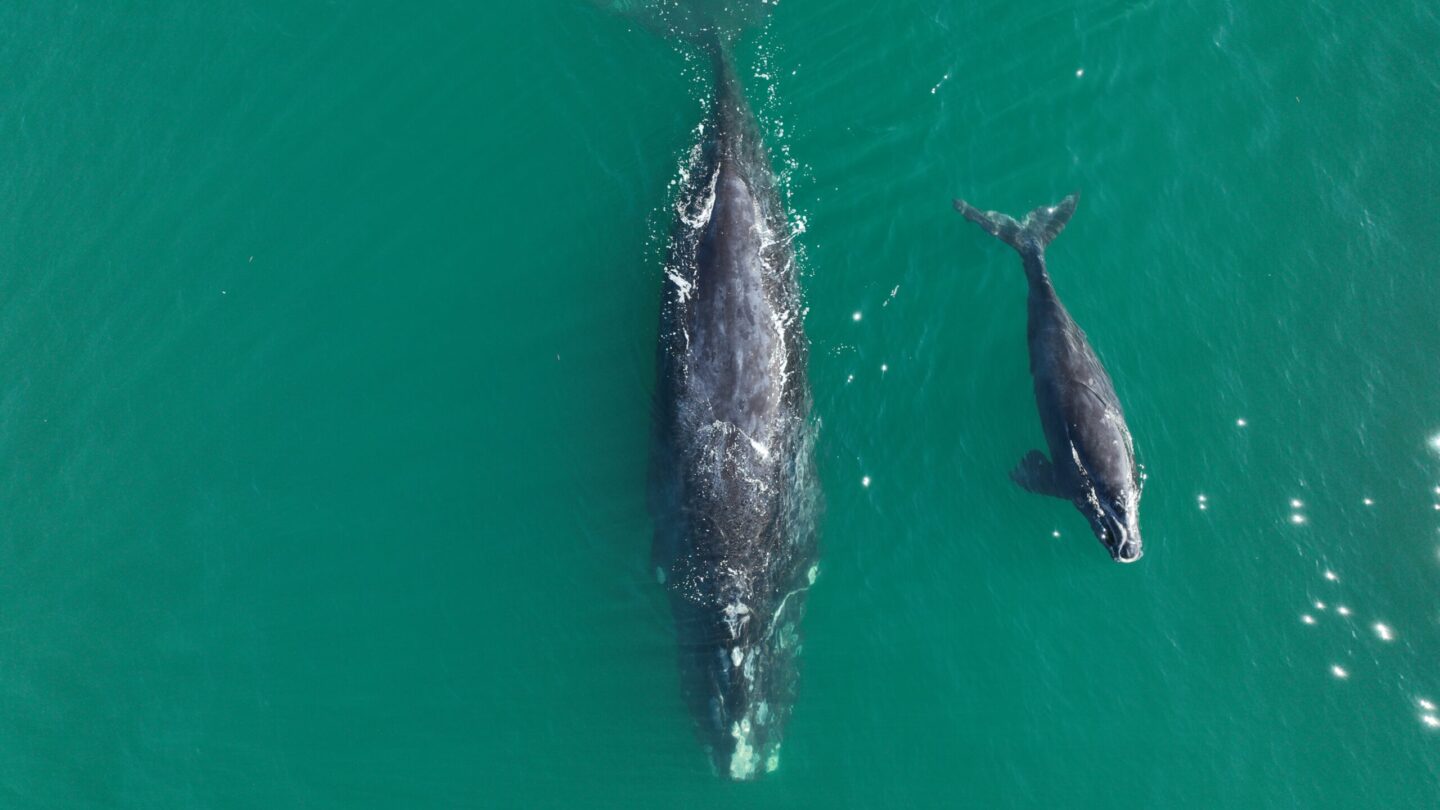

New population estimates for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale are pointing toward a positive trend.

The critically endangered North Atlantic right whale population has been dipping in recent years during an “Unusual Mortality Event,” according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). From 2017 to 2023, a statistically above-average number of whales have been injured or found dead.

Each year before the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium’s annual meeting, the government agencies and researchers tracking and trying to preserve the population review the previous year’s population estimates and make some tweaks, according to New England Aquarium research scientist Heather Pettis.

“When we do these annual estimates, it gives us an opportunity to sort of go back in time using the most up-to-date data we have,” Pettis said. “That allows us to capture individuals that have been added to the catalog that we keep track of, individuals and haves that have been added to the catalog, and it gives time for the whales that we don’t see them die but they disappear.”

2022’s North Atlantic right whale population has been recalculated to 356 individuals, and the adjusted number for 2021 is 364, including new calves that hadn’t been added to the catalog before. Altogether, that’s up from about 340 reported in 2022. The whales are about to enter their breeding season, where they will have their calves off the southeastern coast, arriving in Georgia around November and staying through April.

This news comes as the federal agency is seeking to decrease human-caused deaths by expanding its speed-regulated slow zones. Right now, vessels over 60 feet long self-report their speeds in slow zones that change depending on where the whales are in their migration cycle. During the summer, the slow zones are farther north, and during the fall and winter, when the whales migrate south, those northern zones go back to regular speeds while the southern stretches begin their 10-knot maximum season. NOAA has proposed including vessels 35 to 65 feet long under these speed rules as well.

This proposed change has sparked fierce debate. Advocates for the whales argue it is imperative to quickly increase measures to protect whales. Two whales have died so far in 2023, one a few-days-old calf that died for an unknown reason, and an adult by a boat strike. The adult was found washed ashore in Virginia Beach, and NOAA identified the injuries to be consistent with a boat strike.

In Georgia, some local and state politicians have come out against the proposed speeding rules. District 1 Rep. Buddy Carter voiced opposition on the basis that the new rules will negatively impact safety for boaters and harm the economic industries on the water, such as charter boats and fishing.

But advocates for the North Atlantic right whale argue enforcement of the speeding rules is flagging.

Jim Brogan, campaign director for environmental nonprofit Oceana’s campaign to save the North Atlantic right whale, said this change is a protective measure that will decrease the likelihood of human-caused harm to right whales. However, enforcement is lacking. Oceana crunched the numbers based on self-reported speeds from vessels 65 feet and longer and found the majority are speeding despite the NOAA slow zones.

“They’re either compliant or non-compliant based on their self-reported speeds,” Brogan said. Oceana calculated compliance by placing any boat that went over the 10-knot speed at any point in its journey through the speed-regulated zone in the non-compliant category.

In the coastal region where the whales have their calves, Oceana said 85% of vessels speed off the coast of North Carolina down to south Georgia.

Using the same data, NOAA came to a different conclusion. NOAA Fisheries compiled the vessel trips through those speed-restricted zones, called Seasonal Management Areas, for boats with a minimum of two AIS data records in the trip. Then, they measured the proportion of total distance traveled in that zone at 10 knots or less based on a calculation of distance-weighted average speed.

The federal agency released an interactive dashboard with updated graphics of vessel compliance. It breaks down what types of vessels are in the data set and the boats’ speed and uses green, yellow, orange and red categories to show different severities of speeding and which types of boats tend to speed the most and worst.

This data only captures self-reported speeds for boats over 65 feet. But Brogan said while researchers can’t assume smaller boats behave similarly to these large vessels, they should still be included in the rules.

“What we do know is that there are a number of cases of smaller boats in that 35 to 65-foot class that have hit and killed North Atlantic right whales. So we know that the smaller boats are dangerous to whales and that there are a large number of smaller boats that potentially could be in this whale habitat,” Brogan said.