Faith makes up the foundation on which Sweet Auburn was built. Even with the many changes in infrastructure, culture and businesses throughout the area, Wheat Street Baptist Church, Big Bethel AME and Ebenezer Baptist Church remain in service to the community.

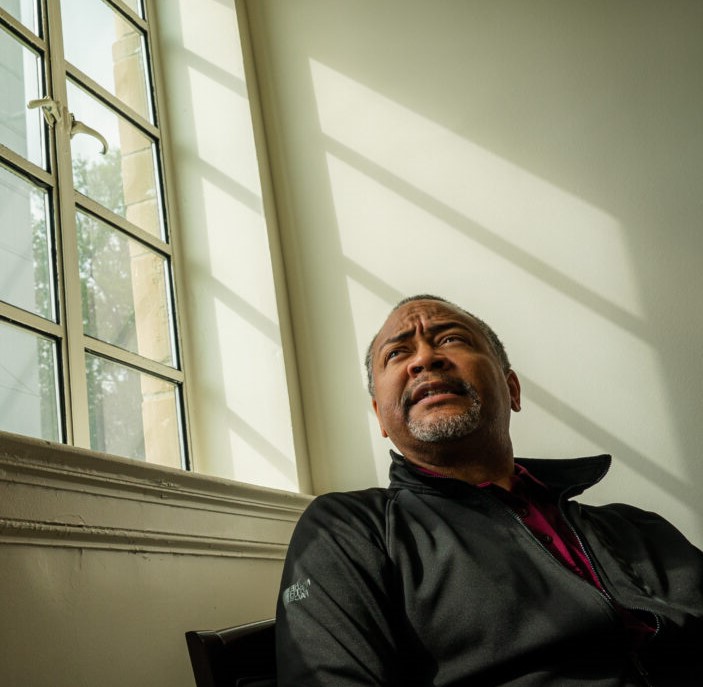

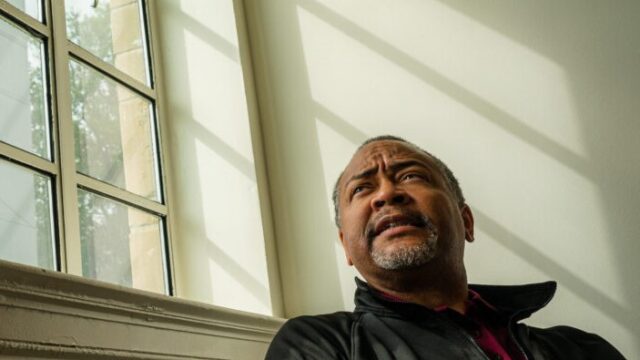

“I think churches have been both a part of the theological and social fabric [of Sweet Auburn] … and I think that they are playing a role in this new wave of revitalization,” said Rev. Dr. John H. Vaughn, executive pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church.

The mission of each congregation is to provide a place of guidance and support for all community members. The work is meaningful but not without its hardships.

Crime in the area has led to robberies, drug deals and gun violence outside of the churches. A lack of economic development and resources within the community has the churches, primarily Big Bethel AME and Wheat Street, struggling to grow in recent years.

“When I first received the position, some of my friends within the community said to me, ‘John, I hope you do well because Sweet Auburn is not sweet anymore,'” said Rev. Dr. John Foster of Big Bethel AME since 2013.

“Sweet Auburn’s still got a long way to go … but I’m very proud of all the work and accomplishments that I and my congregation have done.”

The church, recently celebrating its 175th anniversary as a congregation, was originally founded in 1847 outside of Atlanta at a time when all of its members were enslaved.

After the Civil War, the church based its congregation in a building four blocks away from its present location on Auburn before moving into its current facility in the early 1920s.

“This building was built by the sons of slaves … they built it saving their nickels and dimes before the days of big saving loans,” said Foster. “And the reason that we are still here, it’s not because we preach so well or sing so well. It’s because of our service to the community. That’s how we’ve gotten to where we’re at here.”

Foster notes that the church has several programs in operation dedicated to making a difference within the Sweet Auburn district.

The church operates a weekly youth academy that up to 50 underprivileged young children attend. It also retains ownership of The Trinity House, a short-term housing facility for men recovering from substance abuse disorder and homelessness.

In addition, Bethel Towers, a 180-unit apartment complex constructed by the church in the mid-’80s, provides housing for senior citizen residents living on lower incomes.

“All of our ministries, in one way or another, are trying to help the community,” said Foster.

Foster notes that one of the best additions to Sweet Auburn and the congregation has been Georgia State University. Big Bethel offers a weekly afternoon Sunday service for students interested in becoming a part of the church’s social landscape.

“The 10,000-pound gorilla that I call Georgia State is a great, great addition, and I think about it that way. And I say that what other church … not just for Big Bethel, but for all the churches, has a 39,000-student campus that is right next to us,” said Foster. “It’s an opportunity for us to interact with [students] and to have that as part of our community.”

Foster also notes another notable Atlanta college that has an association with Big Bethel.

“Morris Brown College was actually founded in the basement of Big Bethel in 1881,” said Foster. “We were not in this building at the time, but it was around that time where we had a meeting and decided that we wanted to start a college. Since then, we give money to keep Morris Brown going.”

The church also opened its doors to members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a Civil Rights organization formed by Southern college students during the mid-20th century.

“When you look at the Auburn community, it was a physical center for the Civil Rights Movement, but it was also a spiritual center for it,” said Vaughn.

The minister says that since its early days on Auburn, Ebenezer and his colleagues at Big Bethel and Wheat Street have been dedicated to the fight for social change and human rights. Members from the churches served in positions for many of the Civil Rights organizations throughout the community.

“One of the things that has been really an honor for me is at funerals, you hear people tell these stories of ‘they weren’t the main people of the Civil Rights Movement, but on the weekend, they were a security officer for the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference]’ or ‘they were a part of organizing for SNCC,'” said Vaughn.

He also notes that although the church is best known for its association with former co-pastor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., it was the leaders of Ebenezer who came before him that influenced his principles and nonviolent approach for change.

“We remind people that Dr. King Jr. didn’t appear out of nowhere. He came out of a context which was this church,” said Vaughn. “A.D. Williams was fighting segregation, he was fighting housing issues and voting issues from early on … and ‘Daddy King’ [Martin Luther King Sr.] was his son-in-law … and followed in his footsteps.”

“‘Daddy King’ was always prominent with social justice and civil rights. He was the spokesperson for social justice all throughout this street,” said Foster.

“[Williams Holmes Borders Sr.] was kind of the godfather of [Sweet Auburn]. He was the one who believed that churches not only need to have their sanctuary and Sunday schools, but they also needed their own stores and their own housing. That was the whole motivation … that’s why Big Bethel got into it. We were following the model set forth by Borders.”

A respected community leader and pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church for nearly 50 years, Borders Sr. was essential in the pattern of churches on the street acquiring property and land ownership within Sweet Auburn, including the start of church-invested businesses and credit unions.

“One of the things the churches did that were unbelievably important was create what I believe are mutual benefit companies, that were created to give dignity in burying your loved ones. You could pay them a little bit on a monthly basis, and if your loved one passed, you had the ability to buy a casket and a plot of land and that sort of thing,” said Lejuano Varnell, the executive director of Sweet Auburn Works, Inc., a nonprofit economic development organization created to preserve the history of Sweet Auburn and its neighboring streets.

In 1972, The Wheat Street Towers, a senior living facility located across the street from the sanctuary, was opened.

According to Eric Borders, grandson of H. Borders Sr. and president of the Wheat Street Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting educational and philanthropic initiatives within the Auburn community, the church was able to accomplish these feats at the time due to the efforts of loyal volunteers within the church.

“Some of the folks in the church were legends of their time … you had a really progressive, large congregation,” he said. “I think my grandfather was the inspiration, but these folks were the enablers. They would step up, do things and get things accomplished.”

Borders noted that his grandfather’s presence and dedication not just to Wheat Street but also to the Sweet Auburn community made him a trusted and respected community leader.

“He lived in the neighborhood. He would sit on the porch of the parsonage with his gate open. He always made himself available to talk with not just members but anyone in the community who needed to speak to him,” said Borders.

“All of the congregation members lived in the community, compared to now for many churches, where you have members commuting … the pastor drives into the parking lot, goes into and does the service, and leaves after five minutes.”

Borders’ sermons brought, at its peak, thousands of residents into the sanctuary on Sunday.

“Martin Luther King Jr. on Sundays would come across the street from Ebenezer and would sit in the balcony and watch my grandfather … it held a great influence on him,” said Borders.

After the retirement of Borders Sr. in 1983 and the migration of a lot of Sweet Auburn residents to other regions of Atlanta, Wheat Street began to experience a decline in members and resources.

The Foundation’s Education Building, in recent years, has become a renewed source of community activity within the Wheat Street campus based on a partnership with the Atlanta Center for Self-Sufficiency (ACSS). ACSS, the primary tenant in the Education Building, is a non-profit that helps roughly 200 clients a year get back on their feet via job training, interview preparation, and job placement.

“In this building, for example, we have programs running every day, Monday through Friday. We’re really happy about what we’re doing and how we’re helping the community,” said Borders. “Our whole mindset has been to basically redevelop our campus. It’s not only just for our congregation because our congregation is only a fraction of what it used to be.”

“Today Wheat Street … you’re lucky to have 50 people there. This large church that used to be the icon of the community,” said Foster, whose church offers both in-person and virtual experiences in person, reaching an average of over 300 members every First Sunday.

Borders and Foster also note that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, older members of the congregation, many of whom have been with the church for over half a century, were hesitant to attend in-person services, changing the dynamics of participation and events.

“Now Ebenezer did well,” said Foster. “They rode the wave of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and built the new church and new center. And God bless them.”

“We’ve always had a global footprint, but our digital growth has just been geometric. We have Sunday viewers in all 50 states all over the globe and members in other states,” said Vaughn. “There’s this whole new global and national Ebenezer that has begun to happen.”

While he does attribute the church’s exposure and popularity to the legacy of Dr. King, he also says that the ministry continues to stand on its own in providing the community with a strong source of guidance, spiritual support and community service work.

“When people oftentimes want to start marches, they come up in front of our church. They come here and gather here because it represents a sense of a spiritual center and hub that is connected to social change that is still prevalent today,” he said.

“I love this area so much, and I can’t wait to see how we take it to the next level.”