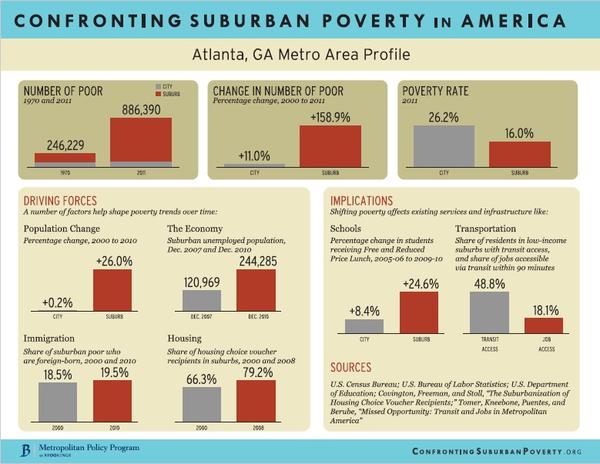

The storybook picture of life in the suburbs includes things like emerald lawns and a certain degree of affluence. In reality, 88 percent of the region’s poor live in Atlanta’s suburbs.

“I know where I’m supposed to be.”

Carole Williams wasn’t at all sure at first that she wanted to be part of this story.

“I didn’t recognize that I was living in poverty until you called and said, ‘Oh, we’re doing a story on that,’ and I’m like, ‘Oh, you are, so what’d you call me for?’”

After saying this, Williams offers up a big congenial laugh.

“Poverty” just isn’t a word she identifies with. She points out that she and her niece live on a nice, suburban street, in a nice house … She pauses. “Without a lot of furnishings, or comforts that we’d like to have.”

Indeed, the walls are bare, and there’s little furniture in this house on an Austell cul-de-sac, where she’s lived for the past 13 months. Still, she insists that she doesn’t feel impoverished.

This is why it demoralized her when she recently had to make the 12-mile drive to Marietta to apply for food stamps.

“Because, um, it’s emotional,” she said. “It’s more than just paperwork. It’s the dramatization of, you know, ‘This is where you’re at.’ The whole tone of ‘I’m needy’ doesn’t sit well on your identity. Not me, anyway.”

Williams used to help other people apply for food stamps. It was part of her job as a New York social worker. She lost that job when her only daughter died — and she fell into a depression. That’s what brought her here to live with her niece in January 2015.

Before then, she was making a fair income, and going to work every day. She pauses and shakes her head. “I know who I am, and I know where I’m supposed to be,” she says. “I’m still living in adversity.”

Atlanta’s Suburban Problem

“What we’re seeing,” says Katrina Deberry, senior program specialist with the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC), “is that a lot of regular families are living in this kind of hidden poverty.”

This could mean the neighbor whose life seems to fit the suburban status quo, “but who may be struggling to feed their family, who may have to go to a food pantry to supplement, or who are having a really difficult time making ends meet.”

Between 2000 and 2013, poverty in Atlanta’s suburbs had the highest rate of change of any metro region of its size.

How did this happen?

Kim Anderson, CEO of Families First, a nonprofit that serves low-income Atlantans, says the issue is complicated, but that today, poverty has hit Atlanta’s suburbs “primarily because that’s where affordable housing is.”

Since the late 1990s, Atlanta has demolished many of its public housing projects, scattering its former residents. These days, most apartments built in-town are high-rent luxury units, tough for middle or low-income people to afford.

Housing in One Place, Jobs in Another

But if there’s cheaper housing outside the perimeter, that doesn’t mean the jobs are anyplace near it, says Anderson.

“A year or so ago, the cheapest rents were out in the Lawrenceville area,” Anderson says. “The largest number of entry-level jobs were in Kennesaw, or the airport, or downtown. So, if you don’t own a vehicle, it’s literally impossible.”

This dependence on cars in the suburbs drains the budgets of poor families, making it even harder to get out of poverty, says the ARC’s DeBerry:

“If you’re spending 50 percent or more [of your income] on transportation and housing, you don’t have a lot left for anything.”

A Confusing Geography

Fortunately, Carole Williams has a vehicle, but it’s one she shares with her niece, who has a job and two kids. Planning her days was a lot easier back in New York, where she would just walk or hop a train.

This relates to something that happened last year, at a time when money was running especially tight. Williams visited Douglasville to apply to a program that helps low-income households with utility bills.

“And I’m taking my ID and my employment situation, and my Georgia Power bill,” she says. “And when we got there, they were filling it all out and they come to the point where he says, ‘Wait a minute. You live in Cobb County. We can’t do this.’”

Williams’ family actually lives on the border of Cobb and Douglas Counties.

“So, what happened was we had to go to Marietta and do it over again,” she said.

But not until the next appointment was open, one month later. Which meant Williams, her niece and her niece’s two children spent the next couple of weeks in their suburban house without power.

Despite everything, Williams remains optimistic. She’s taking classes now to change fields and become a dialysis technician. She says, “This is just not our season right now, but by the end of the story, it might be.”

That will depend largely upon her ability to access the resources she and her family need, to leave this season behind.