It turned out that the seemingly innocent chili dog was the culprit.

Cape’s allergist said it sounded like she had an alpha-gal allergy. Most people affected by it become allergic to red meat.

Alpha-gal is a carbohydrate molecule that is not found in humans, but occurs in certain mammals, including deer, pigs, cows, rabbits, horses and lambs.

“To this day, I would have never thought, on such a beautiful spring day that I would be feeling so great, being with a client, finishing work, going to the grocery store, and then something I had eaten all my life had become poisonous to my body,” said Cape. “At this point, things became very serious to me, and I knew things were going to change.”

Cape was tested and turned out to have an alpha-gal allergy more serious than most. Any product from a hoofed animal can make her break out in hives or go into anaphylactic shock. That includes uncooked dairy products, including uncooked milk, as well as gelatin or gelatin products.

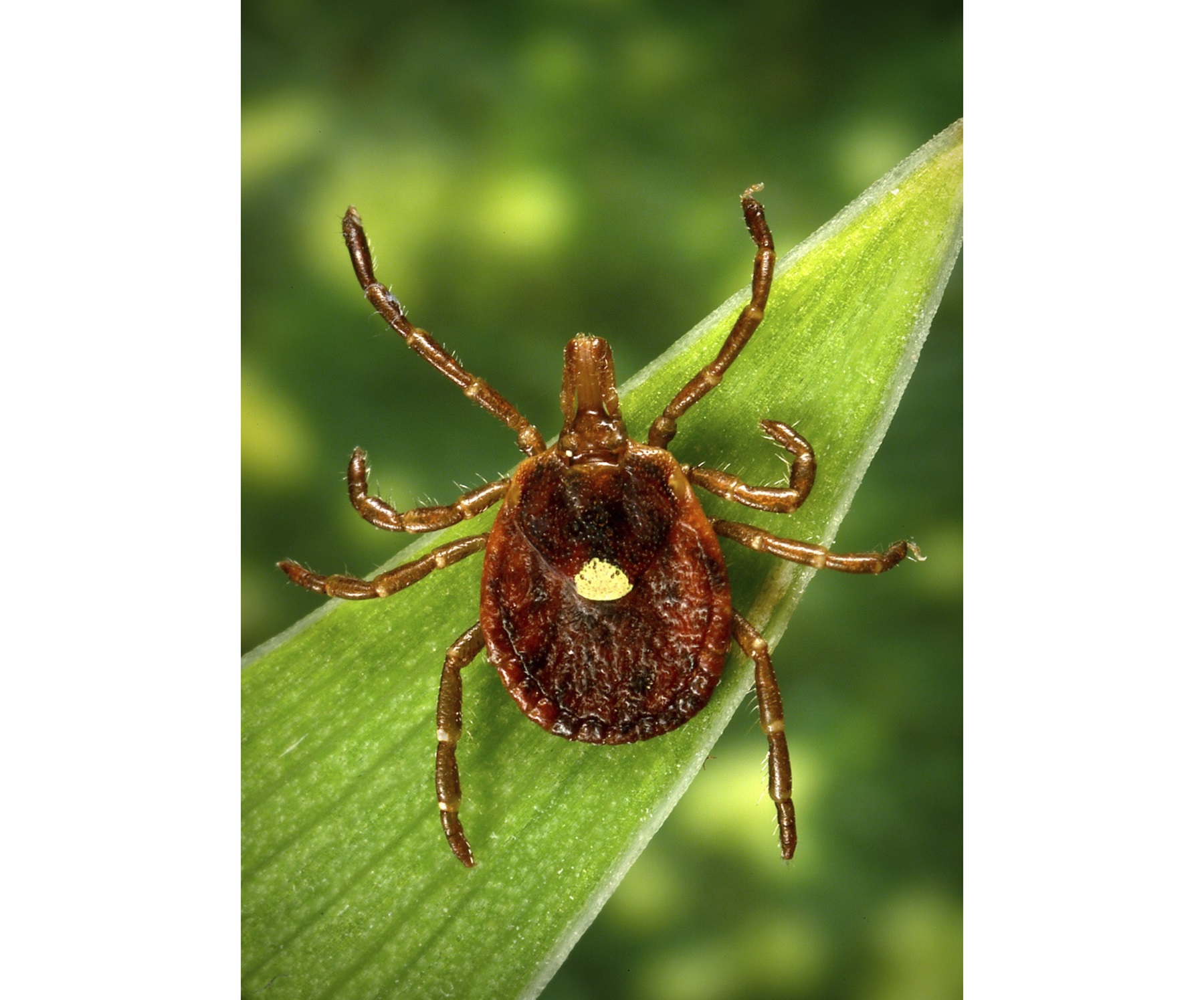

Another Reason To Avoid Ticks

Researchers think the alpha-gal allergy is caused by a bite from the Lone Star tick. There’s no definitive proof of that, but there is strong circumstantial evidence. Dr. Scott Commins, an allergist and researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said the thing that most alpha-gal allergy patients seem to have in common is a history of tick bites.

Commins was a research fellow in Dr. Thomas Platt-Mills’ lab at the University of Virginia about 10 years ago. Platts-Mills is credited with discovering the existence of the allergy after patients began having reactions to a chemotherapy drug that contained the alpha-gal molecule.

Platts-Mills then created a test for the alpha-gal allergy.

“We didn’t know much about the meat allergy at all. But we were essentially initially investigating an alpha-gal allergy that was occurring to this cancer drug,” said Commins. “And around the same time, we had few patients that would come to the allergy clinic at UVA and say, ‘I think I’m allergic to beef or lamb,’ so we tried to put two and two together.”

For food allergies, it’s unusual to have a reaction to multiple different animals or products.

“The idea that these patients were allergic to beef, and pork and lamb and rabbit, all at the same time was very odd. So we began to think about what is the same in all of those animals? And we realized alpha-gal fit the bill,” said Commins.

The doctors at the UVA clinic ran blood tests and found their patients complaining of meat allergies did have positive alpha-gal tests – the connection between alpha-gal and the meat allergy was confirmed. That was in 2009.

Around this time, Platts-Mills himself contracted the alpha-gal allergy. He had been hiking and noticed that he had tick bites. His body also had increased levels of alpha-gal antibodies, a sign of the allergy. This was when Platts-Mills and Commins started to suspect that tick bites might be the missing link to how the alpha-gal allergy is contracted.

Dr. Cosby Stone, an allergist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, said research hasn’t yet proved that the allergy comes from the tick, but it does seem to be the most likely cause.

“You go walking through the woods. And you get bitten by a tick. And that particular tick has just fed not too long ago on a deer or a cow or some other mammal,” said Stone. “When it bites you, it then releases a little bit of the blood from that animal that it fed on last, into your body. And the combination of the bite from the tick and the blood activates your immune system.”

This is the hypothesized mechanism for the allergy that Stone, Commins and Platts-Mills adhere to. They have also observed that once a person’s immune system is activated, it creates antibodies against the alpha-gal molecule. The next time that person eats red meat, the meat is broken down in the digestive tract. Because digestion takes some time, the meat doesn’t start getting absorbed into the bloodstream until generally about four to six hours after the person has eaten, which can lead to the delayed allergic reaction that many experience.

For some people, those allergic reactions may be more severe than others.

Greg Brooks’ lips swell and itchy welts pop up if he eats red meat. But so far, he doesn’t seem to have any problems with reactions to milk or dairy by-products, as Carole Cape does.

Brooks is the community and public relations director for Walton EMC, an electric power company that serves parts of the Atlanta and Athens areas. He started having allergic reactions seemingly at random — sometimes in the middle of the night, one time while he was camping. Every time his palms would itch.

“At first I thought my allergic reactions were to mold or mildew, then I thought it was maybe peanuts,” said Brooks. “I had absolutely no clue that it was red meat.”

It wasn’t until Brooks was on a work trip in Nashville that his alpha-gal allergy woke him up suddenly around 3 a.m. His stomach was severely cramping, his windpipe was swelling, and he had a large rash, along with itching and welts. Brooks was given antihistamines at a local hospital and came out fine. But he also made an appointment with an allergist in Athens.

“The doctor asked me questions about my allergies – when I told him they happened in the middle of the night, he said, ‘Have you been bitten by ticks?’ And I actually had,” said Brooks. “A couple of months ago, I got about 50 tick bites covering my legs when I was out in the woods by my house. But what set up the red flag was that it happened in the middle of the night.”

Stone, the doctor at Vanderbilt, is one of the few researchers trying to understand why some people’s allergic reactions to meat are more serious than others.

He said there are no definitive answers yet, but it’s possible that a person’s genetics, immune system and general health can affect allergy severity.

Doctors working at Vanderbilt’s Asthma, Sinus and Allergy clinic have also noticed that some patient’s allergies eventually get better over time. They’re the patients who are avoiding all meat and not getting more tick bites.

That’s exactly what Carole Cape is trying to do now.

As a successful real estate agent in Athens, she constantly finds herself in tricky food situations. Her new constant companions are liquid Benadryl, two EpiPens and a medical alert bracelet.

Figuring out what she can and can’t eat has been difficult. It’s left her isolated from her co-workers and fellow church members.

“There’s no more eating out. I have to gracefully bow out,” said Cape. “That’s because I have to be certain the restaurant wouldn’t cross-contaminate their utensils with red meat or dairy products. Or use beef oil. If the restaurant was doing either of those things, and I ate something, I would automatically go into the shock.”

Her reaction to milk products unexpectedly came up a couple of months ago, after she ate a strawberry sprinkled with artificial sweetener containing milk products. She was in her car driving to a model home when her throat tightened. She pulled the car over and took Benadryl, which stopped the reaction.

But Cape worries there may be other things she’s allergic to which have just not shown up yet.

“That’s why I feel at times that I’m living life on the edge,” she said.

But Cape has found some comfort in joining an online community of others living with alpha-gal allergy.

“It helped me to see that there are other people out there living like I am,” said Cape.

Brooks actually connected Cape to the Facebook group after he read about her experience with the allergy in the local Athens paper.

Brooks has experienced the same feeling of isolation that Cape has expressed.

“Food is communal. Socially, you’ll go to something and all that they have is red meat,” he said. “People will be like, ‘Why aren’t you eating any meat?’ Then you have to explain.”

Both Brooks and Cape are now committed to spreading the word about their allergy.

“I really have tried to talk to my family and a lot of people that I know who go in the woods and so forth, to keep from being bitten by ticks,” said Brooks. “And put that repellent on while they go out.”

Brooks has also written an article for Walton EMC’s quarterly bulletin, titled, “Meet my new gal.” He wanted to educate his co-workers about his new allergy.

A Voice Of Experience

Meanwhile, Cape is trying to educate the public and members of the medical community.

“Recently, just last week I saw doctors that were specialists,” said Cape. “But they were like, ‘What is alpha gal?’ The alpha-gal allergy is just not out there yet.”

But that dearth of awareness may not last long.

Both Commins and Stone said the numbers of patients diagnosed with alpha-gal allergy have increased in their respective clinics in Chapel Hill and Nashville over the years.

They think it may be attributed to a backlog of patients who couldn’t be officially diagnosed with the allergy until 2009. Other experts have said that increases in deer populations may be leading to increasing numbers of ticks, and thus more tick bites. The range for the Lone Star tick is most of the Eastern U.S., and includes parts of the Midwest and New England.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not have a national surveillance system in place to monitor the number of alpha-gal cases.

But Platts-Mills, the UVA researcher who discovered alpha-gal allergy, has set up his own makeshift online monitoring system via a website called ZeeMaps. People who have alpha-gal allergy can self-report by placing pins on a world map. And people from the United Kingdom, the continent of Africa, India, Iraq and Australia have claimed their place on the map.

The map is just one step toward further understanding the scope of the alpha-gal allergy that is affecting those in our community, our nation, and also around the globe.

And that’s important to Cape.

“The more that people know about alpha-gal, the more they will be likely to try to prevent tick bites, get allergy tested, and think about their own allergic reactions,” said Cape. “And if I can help spread the word about that, then at least living with this meat allergy is doing some good in the world.”

Victoria Knight is a graduate student studying health and medical journalism at the University of Georgia. She also works as a health reporter for WUGA-FM, the Athens-area NPR station, and has a bachelor’s degree in microbiology from the University of Tennessee. You can follow her on Twitter at: @victoriaregisk

This article originally ran on the Georgia Health News site.