President Biden’s first year in the White House has ushered in record job gains, unprecedented wage gains for low-income workers and GDP growth not seen in decades.

But polls show Americans remain deeply cynical about how the president is handling the economy — and that’s a problem for Biden and Democratic lawmakers heading into November’s midterm elections.

The president and his advisers routinely tout statistics that show how the economy is surging by most traditional economic metrics, seemingly mystified about why the American public isn’t giving Democrats more credit for this boom.

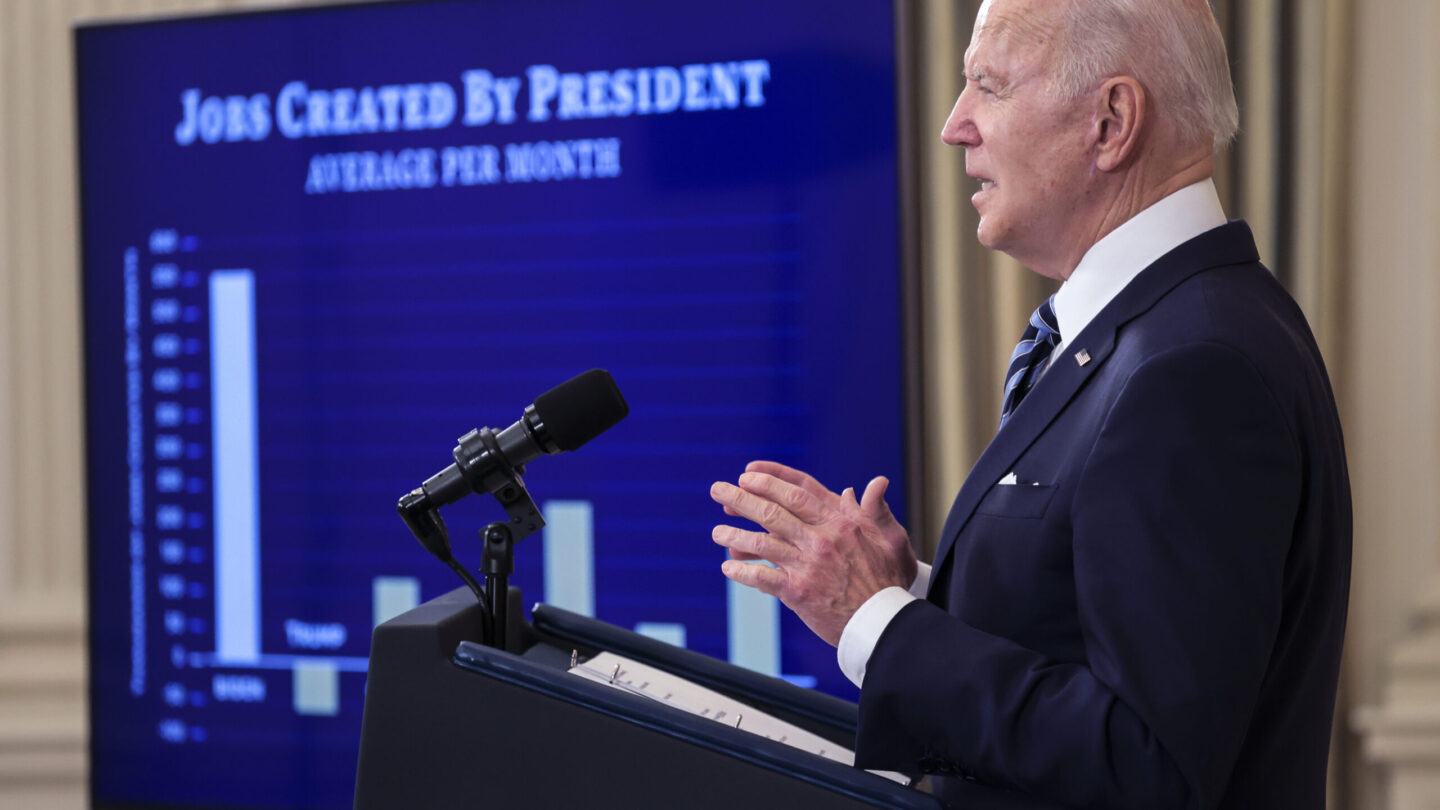

Last week, as the president delivered remarks on the January jobs report, he highlighted that in his first year in office, the economy created 6.6 million jobs.

“If you can’t remember another year when so many people went to work in this country, there’s a reason: It never happened,” Biden said, telling reporters to look at economic statistics dating back 40 years to President Ronald Reagan. “History has been made here,” he said.

Biden is expected to make his latest remarks on the economy on Thursday in Virginia, in the district of Democratic Rep. Abigail Spanberger, first elected in the former Republican stronghold in 2018 by a narrow margin. Republicans are working hard to flip the district in November.

Inflation is surging, and that’s hitting voters where it hurts

Thursday is also the date for the latest report on inflation. The consumer price index has risen sharply in the last year, with inflation most recently climbing to 7% — the highest point since 1982. New inflation data might paint a slightly more nuanced portrait of current economic conditions, but the overall trajectory for inflation has been stubbornly high for months.

Democrats like Spanberger in vulnerable districts have urged the White House to spend less time on its proposal for massive spending on the social safety net and more time on inflation and other economic issues.

Economists and analysts say that people experience inflation on a visceral level and that it tends to outweigh positive economic data points.

“Inflation is something people feel in a different way than they do other economic indicators,” said Jack Lew, who was Treasury secretary during the Obama administration. “The price of gas is reflected every time you get a tank of gas.”

Larry Summers, director of the National Economic Council under President Barack Obama, has been sounding the alarm on inflation for months.

“More unemployment is the difference between a job and not a job for 2 or 3% of the population. More inflation is higher prices for 100% of the population,” Summers said.

Inflation makes people unhappy in ways that are disproportionate to the actual concerns that economists have about inflation, he said.

“People tend to think that … higher prices are something that’s being stolen from them,” Summers said.

In other words, people feel ripped off by inflation.

There’s not that much Biden can do about inflation

Inflation is complicated. Whether it goes up or down is largely in the hands of the Federal Reserve, which is responsible for interest rates.

Darrick Hamilton, an economist at the New School in New York, said context is key. “We just experienced the deepest decline on record. And likewise, the quickest recovery on record,” Hamilton explained.

“A lot of that had to do with an intervention from the government that allowed us to withstand that pandemic. So there’s going to be inflation.”

Some economists point to last year’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 aid package known as the American Rescue Plan as one of the reasons behind the inflation seen today, but the alternative could have been more dangerous. They fear that without the COVID-19 relief money, the economy would have spiraled into a recession.

Hamilton argues that the inflation debate has been driven by “strategic political gaslighting” from Republicans that is “exploiting anxiety around things like inflation.” He agrees with the Biden administration’s assessment that the current spike in inflation is temporary.

It’s hard for Biden to take credit for the economy, given rising prices

Wages have risen for low-income workers, but many feel like the raises they’ve received have been wiped out by rising prices.

“There’s an old notion that you cannot tell people how they feel and that they feel better than they do,” said Lew, the former Treasury secretary.

The Biden team has to balance taking credit for accomplishments like the COVID-19 relief bill with the reality that COVID-19 and inflation are still very much on the minds of people every day, he said.

Lew recalled the Obama White House facing a similar messaging challenge during the recovery from the 2007-2009 Great Recession: how to tout the president’s accomplishments while acknowledging people still needed more help.

COVID-19 fatigue is also feeding into how voters feel about the economy

On top of inflation woes, many voters are frustrated and exhausted by the coronavirus pandemic and see the economy through that lens. Analysts and pollsters say voters remain anxious about economic instability resulting from some future new, unexpected coronavirus variant.

There is evidence that people’s views of the economy are often based on expectations of change, rather than the current reality, economists said. So after a fleeting summer of optimism, as the pandemic has dragged on, people have become more pessimistic about their economic future.

“Until the time when the pandemic is done, you know people are going to be upset about the economy,” said Austan Goolsbee, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Obama administration.

“It doesn’t matter if you read in the paper that the unemployment rate is way down and we added more jobs than we’ve ever added in a year. It doesn’t, as long as we are in a worse spot than we wanted to be,” he said.

Goolsbee sees the president’s approval rating on the economy as essentially a barometer for how people feel about the pandemic. And ultimately, until COVID-19 isn’t constantly hanging over their lives, he’s not convinced that even a lower inflation rate would have the power to fundamentally alter how people feel about the economy.

Biden has changed how he talks about inflation, but needs to repeat it more often, pollster says

Democratic pollster Celinda Lake says voters in polls and focus groups have been anxious about the economy for months.

“The instability is really unnerving the public,” she said. Voters are worried about economic volatility and the rising cost of living.

“It hits them every day, it hits them every purchase and it really makes them feel depressed about the economy,” Lake said. “They’re convinced that wages are not keeping up with the rising cost because you get a paycheck twice a month — you buy something that’s more expensive every day.”

Initially, the president and his team used the term “transitory” to insist that price increases were not a permanent thing.

But over time, Biden pivoted and began acknowledging more of the pain that people were feeling at the gas pump and the grocery store.

“I think he’s doing a lot of that in his current messaging, but we’ve got to repeat, repeat, repeat,” Lake said.

The president’s approval ratings are a big factor for the midterm elections

Emory University political science professor Alan Abramowitz has looked at the results of every midterm election dating back to World War II and says a president’s approval rating is a far better predictor of what will transpire in the midterms than any economic indicator.

“No matter how good or bad the economy is, if people perceive it as bad, that’s going to probably hurt the president and hurt the president’s party in the midterm election,” he said.

Since inflation seems to be dragging the president’s numbers down, analysts say Biden needs to make it clear he’s concerned about the problem — whether or not he has the ability to actually fix it.

“Bill Clinton once said when there’s a problem, people don’t necessarily expect you to solve it overnight, but they have to catch you trying,” said Bill Galston, former domestic policy adviser in the Clinton White House and now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

“So, if I were Biden’s scheduler, I would have him out a couple of days a week dramatizing his commitment to the fight against inflation.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))