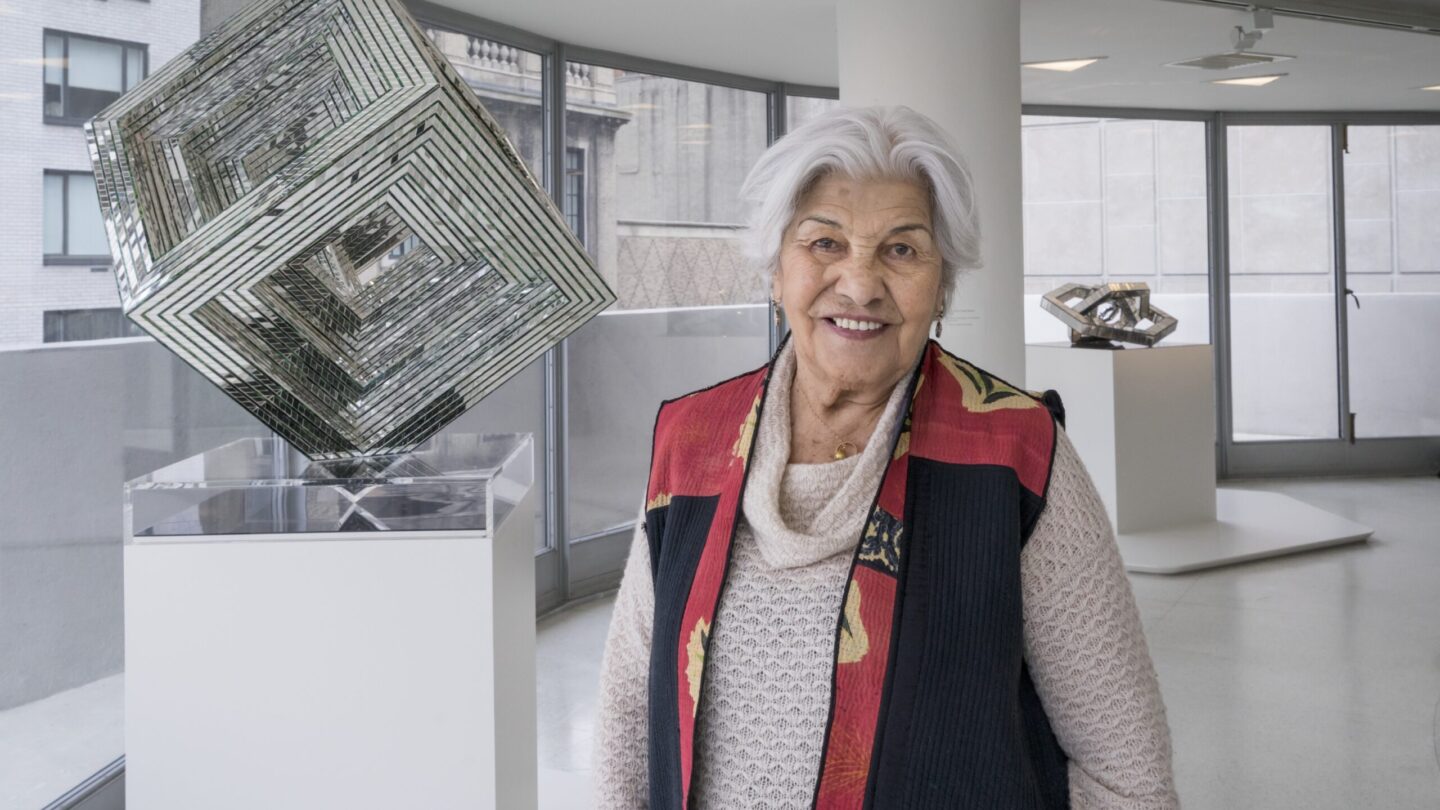

In 2019, the art world mourned the passing of Monir Farmanfarmaian, an Iranian artist renowned for her beautiful geometric mirror sculptures. She’s honored today by Iran’s only museum dedicated to a single female artist. The first posthumous exhibition of work by Monir Farmanfarmaian, “A Mirror Garden,” is on view through April 9 at the High Museum. The show includes several of her famous mirror sculptures, as well as drawings, paintings, and textiles.

The High Museum’s curator of modern and contemporary art, Michael Rooks, joined “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes to share more about this singular artist and her work on display.

Interview highlights:

An artist’s journey of discovering geometry in nature:

“The title of the exhibition actually refers to Monir’s memoir. It was co-written by Zara Houshmand, who will be here on Feb. 23 to talk about Monir’s life and career. But in that memoir, the artist reflects upon her childhood garden in Qazvin, Iran, where she was born in 1922, and flowers and birds, nature was something that really was a charm to her as a child,” Rooks said. “Later in her career, she understood that flowers have a hidden geometry, that the array of flower petals actually follows the golden ratio, that they’re arrayed according to the Fibonacci sequence, that there is this beautiful geometry in nature. In fact, her world, she recognized, was dictated by geometry, that everything in the world around us has a kind of geometry, whether it’s hidden or more obvious.”

“In Shiraz, Iraq, there’s a shrine called Shah Cheragh, and that means ‘king of light,’ and it’s a shrine that’s covered from floor to ceiling in fragmented mirror tiles, tessellations of mirror. So when you walk into it, it’s just this resplendent environment, and it’s during that time when she started to connect the dots between sacred geometry and its symbolism, and the discursivity of mathematics,” explained Rooks, “In addition to this kind of revelatory experience of the transcendent, as she watched people in this environment, integrated into this environment in infinity, in the fragmented reflections of their form as they engaged in prayer and supplication.”

A remarkably abundant body of work from Farmanfarmaian’s last chapter:

“The last decade of her life, let’s say, was one of the most prolific moments in her career. So she was making a lot of work. She was making ambitious and complex work at this time, and what’s fascinating, remarkable, is that she started over in Iran in 2004 at the age of 82. You know, 82 years old – most of us would consider that like the late autumn of our lives, right? But that was the beginning, like a second beginning for her, and so she was incredibly prolific showing her work around the world,” recounted Rooks.

“We acquired our sculpture called ‘Muqarnas’ in 2018, and that’s what inspired us to think about curating this exhibition of her work, a mini-survey of her work. And unfortunately, she did die the next year at the age of 96. That compelled us to double down and to revisit the idea for the exhibition, to make it more of a survey demonstrating the arc of her career, rather than focusing on this late period.” Rooks added, “It’s incredible to think that someone can go through all of the things that this artist went through – losing everything to the Islamic Revolution of ’78 and ’79, losing her husband in ’91 – and beginning over in her eighties, being even more fierce than she ever was. That is amazing to me.”

On the exhibition’s featured series of “Heartache Boxes:”

“The ‘Heartache Boxes’ are these assemblage works; they’re collage boxes,” said Rooks. “There are these wonderful little microcosms, for Monir Farmanfarmaian, of her life and the memories of her family and of her childhood, and she began making them in 1998. Her husband had died in ’91. His name was Abol-Bashar Farmanfarmaian, and that was one of the last big losses in her life. When the Farmanfarmaians were exiled to the United States in 1979, they lost everything they had – their wealth, their homes, her studio, and all the work she made in Iran, the collections that she had amassed of indigenous art forms.”

He went on, “So in 1991, when her husband died, I think that led her to reflect on the first half of her life. And these ‘Heartache Boxes’ represent, in a way, diaries. They’re almost diaristic in how they contain these moments from her family life, her childhood, her career. One of the boxes includes specific references to commissions that she received from the UN, for example, for a stained glass window, in addition to another commission in Holland for a set of stained glass windows. So she’s reflecting on her life and career at this moment in 1998, perhaps not knowing that she could ever return to Iran. So it was a way of, again, this kind of resistance to forgetting her life.”

“Monir Farmanfarmaian: A Mirror Garden” is on view at the High Museum through April 9. More information is available at https://high.org/exhibition/monir-farmanfarmaian-a-mirror-garden/.