In 1985, Mtamanika Youngblood, a New York native, and her husband bought a home on Atlanta’s Howell Street NE. The two story home was built in 1890 and had good bones, but needed a lot of work.

It was located a few blocks away from the already opened Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change that had been founded by King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, soon after his death in 1968.

Coretta Scott King was fervently fighting for a federal holiday to commemorate her husband’s birthday while also preserving his “birth home block” when Youngblood moved into her home two blocks away.

In 1985, those two blocks made a world of difference.

When she first saw it, Howell Street in the heart of Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward felt familiar to Youngblood.

“It reminded me in some strange way of the block I had grown up in in New York where here all these little old ladies were sitting on their porches and in New York you sit on your stoop.”

It’s the neighborhood in which years later Youngblood would start Sweet Auburn Works to preserve the history that existed there.

A decade after the race massacre left the Old Fourth Ward mostly segregated, the Great Atlanta Fire of 1917 ravaged the neighborhood.

The fire consumed more than 50 city blocks in 10 hours, stretching from Decatur Street in the south to the end of Piedmont Park in the north and stopping on the east side on Boulevard, just short of what would be Martin Luther King Jr.’s birth home and Youngblood’s future street.

Nearly 2,000 buildings were destroyed, many of which had been made with wooden shingles, and more than 10,000 people were left homeless.

Atlanta’s Fourth Ward had originally been diverse with German and Jewish inhabitants, but the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906 that claimed at least 12 African American lives and injured hundreds of others left the city segregated.

Enforced with Jim Crow laws, black communities shrunk and overcrowded in neighborhoods west of downtown close to the Atlanta University campus, south of downtown in Pittsburgh, Mechanicsville and Summerhill and east of downtown in the fourth ward.

The fabric of the neighborhood shifted as homeowners were replaced by tenants. Apartment buildings often replaced many of the destroyed single-family homes. Commercial buildings popped up parallel to Atlanta streetcar on Edgewood and Auburn avenues as the Old Fourth Ward rebuilt itself.

At this time, the neighborhood was mixed income.

“Everybody lived together because there was no place else to live,” Youngblood said. “Because we had to live here, you had bishops and bank presidents and contractors and lawyers and doctors.”

If anyone needed something fixed or made, a neighbor could do it, which kept business and money within the neighborhood.

The Neighborhood Of King

The neighborhood was booming by the time Martin Luther King Jr. was born in 1929, and so was the rest of Atlanta. While the city’s original success had come from its railroads, Atlanta was becoming a thriving business center thanks to the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce “Forward Atlanta” campaign spearheaded by Ivan Allen Sr. and W.R.C Smith to attract national corporations to use Atlanta as a regional hub.

In 1926, Sears, Roebuck & Co. had chosen Atlanta for its southeastern hub, building what is still today the largest brick building in the Southeast to house their commercial and shipping center on Ponce de Leon. Even former President Jimmy Carter remembers that trips to Atlanta weren’t complete without a visit to the Sears Roebuck store.

“We lived off Sears-Roebuck, buying stuff that wasn’t sold in Plains … The remarkable thing was that you could place your order on the first floor and thirty minutes later you could pick it up. It was like a dream,” Carter said once in an interview about his childhood with Gary Pomerantz, author of “Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn.”

Historian and educator Jerry Hancock has interviewed more than 60 employees who worked in the old Sears-Roebuck building, which we now know of as Ponce City Market.

“Ponce de Leon was the racial dividing line, anything north was white and anything south was black,” Hancock said. “That’s why the street lines change names. For the longest time people talked about this building almost like it was the big wall dividing the black and white communities.”

On the South side of the Fourth Ward, the segregated community had built their own prosperous downtown on Auburn Avenue.

“Our theatres, our barber shops, our world was there,” recalls Daryll H. Griffin, who grew up in the neighborhood in the 1950s.

On Auburn Avenue, black businesses thrived. Griffin remembers her grandfather who opened the first black-owned department store in Atlanta.

“I don’t want to say ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ because he didn’t even have any boots. He was truly self made.”

That was the nature of Auburn Avenue, dubbed “Sweet Auburn” by Atlanta legend John Wesley Dobbs for its vibrancy and economic and political power.

This led to an interdependent localized community where people lived, worked, and invested in their neighborhood. In the 1950s, Forbes magazine referred to the street as the “richest Negro street in the world.”

A Community Of Churches

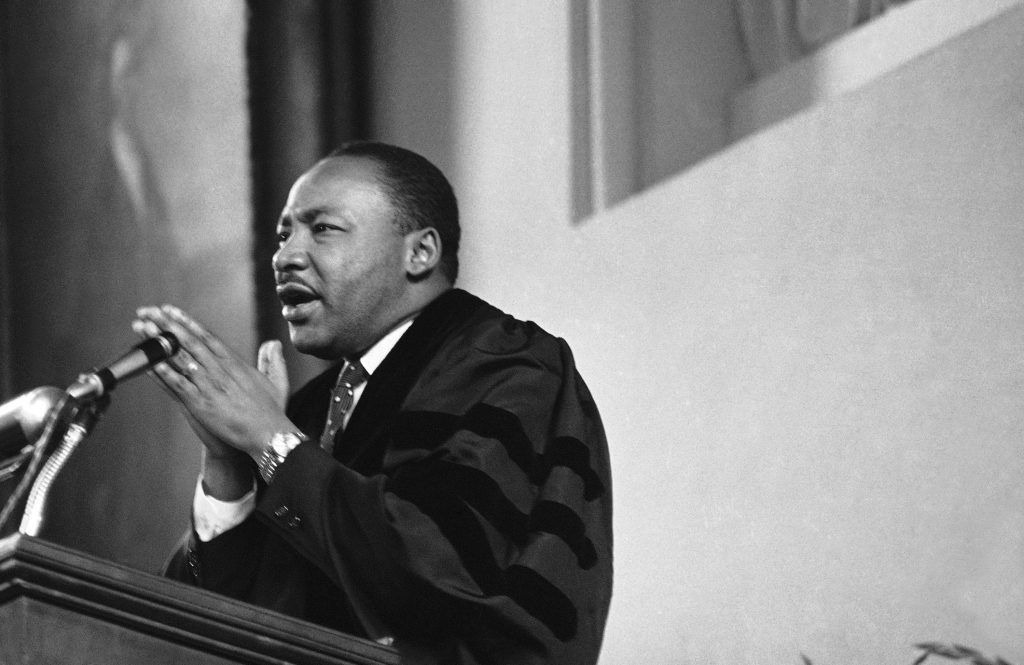

By the time Martin Luther King Jr. was 10, the beginnings of a civil rights movement had already taken hold in the Old Fourth Ward. Pastors were preaching for equality and liberation and community leaders were partnering in their efforts toward advancement.

King came from a family of pastors who were committed to the betterment of their community. His father, Martin Luther King Sr., often referred to as ‘Daddy King’ was preaching at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where his maternal grandfather, A.D. Williams, pastored.

Williams encouraged the community to buy property and King Sr. fought for and made significant gains for the equal pay for black teachers, often hosting meetings in their home for the NAACP or Atlanta’s Civic Political League that had originally been founded by Dobbs.

After being a respected railway mail clerk for 32 years, Dobbs was able to commit his life in retirement to civic service. He became Grand Master of the Prince Hall Masons, arguably the most influential secular organization of the neighborhood and time.

The temple he built on the corner of Auburn Avenue and Hilliard Street in 1937 was a place where men from the various congregations in the neighborhood could come together.

“There was a cross-pollination of civic and political ideas because all outstanding men at the time were Masons,” Youngblood said. “The Masons lifted up men that had a skill. They believed in God and community. They were upstanding men and what that meant to John Wesley Dobbs was that they had to be registered to vote.”

Through his civic engagement and constant presence on the street, Dobbs became known as the unofficial mayor of Auburn Avenue.

The Rev. William Holmes Borders often worked with Dobbs. Borders became pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church on Auburn Avenue (originally named Wheat Street) in 1937. Known for his fiery sermons, Borders would sometimes preach to more than 3,000 people on a Sunday.

Some Sundays, a young Martin Luther King Jr. would be spotted sitting in the balcony listening.

Like Dobbs, Borders was committed to the advancement of African-Americans, but he did this through his church. In his 51 years of pastoring the historic Wheat Street Baptist Church, Borders was consumed with finding a way to connect with and meet the needs of his community.

“Borders believed that people should live in their community, work in their community and worship in their community and make it more prosperous,” said Marty Smith, Lead Ranger at Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Park.

The churches in the Old Fourth Ward often made progress before the city of Atlanta. Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, a stone church known for its blue neon “Jesus Saves” sign, opened Atlanta’s first public school for African-Americans in its basement.

In 1881, Morris Brown College held classes in the same basement before its campus was ready. In the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s Dobbs often used both Big Bethel and Wheat Street to host meetings and events because of the size of the buildings. Dobbs used Big Bethel so frequently that it became known as “Sweet Auburn’s City Hall.”

When Dobbs died, on Aug. 30, 1961 — the same day that nine black students desegregated Atlanta’s schools — he wanted his funeral to be at Big Bethel AME instead of the church he belonged to, First Congregational Church on Courtland Street.

“My reason for this request is my undying love for ‘Sweet Auburn Avenue’; and also, the fact that Big Bethel Church has always been an ‘Open Forum’ for the Civil and Political rights of my people,” Dobbs wrote in his funeral request.

At his funeral, Borders gave the eulogy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke referring to Dobbs as “an oasis in the midst of a desert world sweltering with the head of oppression and cynicism.”

The beginning of what would lead to the civil rights movement nationally had started as a generation of ministers and civic leaders on Auburn Avenue fighting for integration, political power and equal pay.

“Dr. King didn’t fall out of the sky. He was birthed in this neighborhood,” Youngblood said.

“And as he lived in the residential portion of the neighborhood and socialized in the more business and cultural portion of the neighborhood, he got to see and understand what was possible,” Youngblood said. “The national park tells his story but we need to put his story in context and the context is Sweet Auburn and the Old Fourth Ward.”

The Legacy Of A Neighborhood

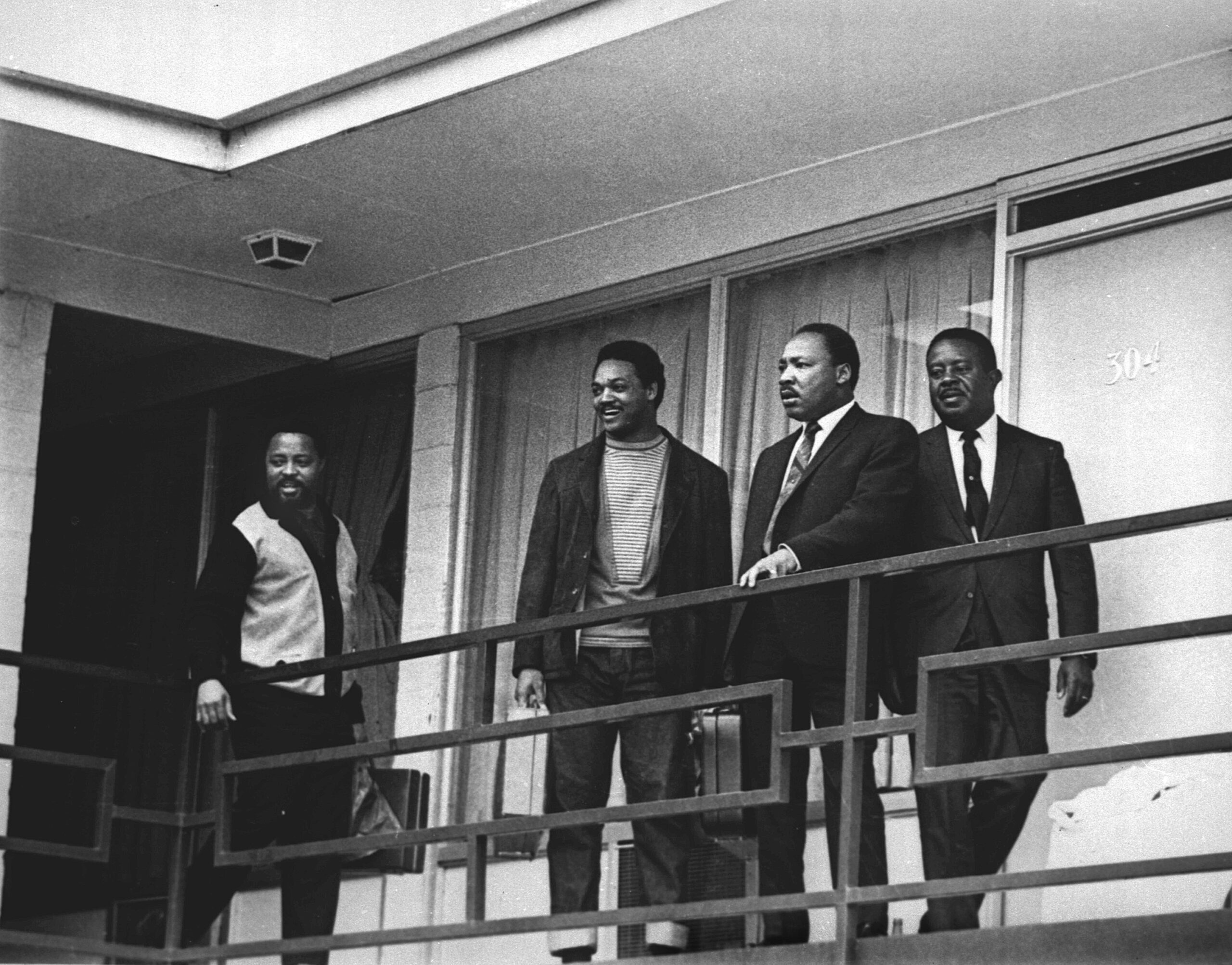

The world was shaken when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968, at the age of 39. A few days later an estimated 50,000 mourners joined in his funeral procession in Atlanta on April 9, 1968.

They proceeded from Ebenezer Baptist Church, down Auburn Avenue, through downtown Atlanta, past the Georgia Capitol and continued on to the Morehouse College campus.

Last year, 50 years later, thousands of people again marched part of the historic route to the Georgia State Capitol to commemorate Martin Luther King. Jr’s life, work, and legacy.

They retraced the first half of this historic funeral route, starting at the Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, crossing over William Holmes Borders Sr. Drive as they passed Wheat Street Baptist Church heading toward downtown.

“The legacy of this neighborhood is where church, business and race and culture came together in the 20th century, but for almost a century, this was the heart of Atlanta,” civil rights leader Andrew Young said.

While the streets have changed to commemorate the heroes of the neighborhood, many of the buildings are still standing thanks to Sweet Auburn Works founded by Youngblood and the Historic District Development Corporation founded by Coretta Scott King in 1980.

In the 1960s, the neighborhood saw an economic decline. First, the city broke up the neighborhood by building interstates through the thriving black commercial center of Sweet Auburn in 1961.

Then desegregation gave African-Americans more options of which neighborhoods to live in, which stores to shop at or which restaurants to go to.

“All of the significant resources went when the people living here left. When they left, there was nobody to sustain the businesses and so one by one by one they closed.” Youngblood explains.

Today, the Old Fourth Ward is on its way up again. Vacant historic buildings are being repurposed.

You can see modern influences as you browse the food stalls at the historic Sweet Auburn Curb Market in the south or eat at the restaurants and browse the shops at Ponce City Market in the old Sears Roebuck building in the north.

Throughout the neighborhood you will see historic homes being preserved as well as new homes popping up. You will see vacant properties as well subsidized housing projects.

On Sunday mornings, you will see people walk into churches in the Old Fourth Ward, many of whom have been going to that church for all of their lives whether they still live in the neighborhood or not. The neighborhood is still mixed income and its legacy is still alive.

“There is a rich sense of history and a great pride in what these black churches achieved in the Deep South.”

“What happened in this church in the ’30s and ’40s, and ’50s, in the midst of the segregated South,” current pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church The Rev. Ralph Basui Watkins said speaking of the community on Sweet Auburn, “Amidst Jim Crow you did this. Being isolated to one street, one community you did this.”

Today hundreds of thousands of tourists flock to 501 Auburn Ave. annually to see the birth home of Martin Luther King Jr.

They go down Auburn Avenue one block to the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change and walk into the Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church to see where Martin Luther King Jr., and his father Martin Luther King Sr. and his grandfather A.D. Williams preached, but perhaps they should continue toward downtown and walk a little further down Auburn Avenue.

After all, as Mtamanika Youngblood says, “This neighborhood created Dr. King.”