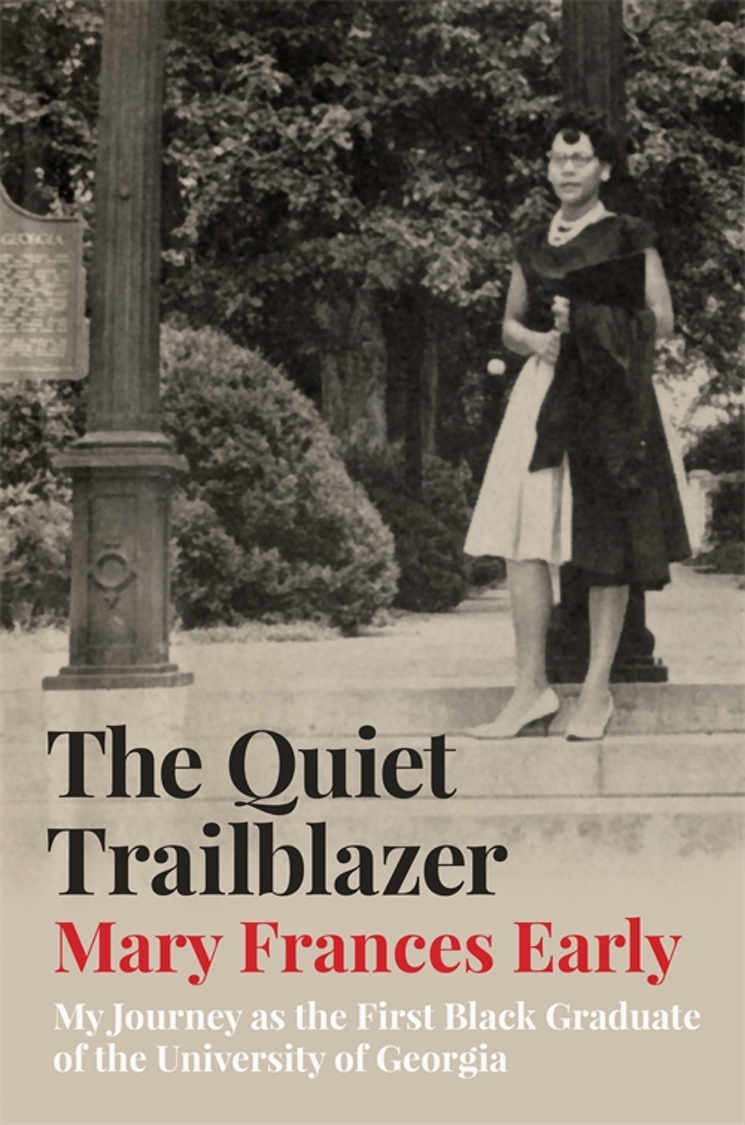

Her name may not be famous, but her role in the Civil Rights Movement was monumental. Mary Frances Early, author of “The Quiet Trailblazer: My Journey as the First Black Graduate of the University of Georgia,” endured acts of extreme racism in her pursuit of education in music. Many considered her an unlikely candidate to become a Civil Rights Movement activist and inspiration, always quiet and studious. Early joined “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes over the telephone to share reflections on her brave years pursuing an education in one of the most violent decades for Black citizens in America’s history.

Interview highlights:

On Early’s love of classical music, and the challenge of its pursuit in the segregated South:

“We couldn’t go to the Atlanta Symphony because it was segregated, and I wanted to go to a real concert, but I could not,” said Early. “At that time, even the Black students were not going as they did later on, at a different time than the whites. So, my dad had us sit down on Sunday evening, and we listened to the Bell Telephone Hour, which played classical music, light classical music, and I loved it. I wanted to participate. I wanted to play in a band, but at that time, I couldn’t.”

“I didn’t want to perform; I wanted to teach. Because my mother had been a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in Monroe, and she had been the top student in the 12th grade class, and so she was asked to take on that position because her teacher was pregnant and couldn’t continue to teach,” said Early. “But I wanted to teach band. And the professor at Clark College, the chair of the department, said, ‘That’s not what ladies do. You should teach chorus.’ Yeah, women’s rights were not very evident at that time. And I said, ‘Well, maybe I can teach both.’ And I did.”

How Early first came to her courageous decision to attend UGA:

“I was in my fourth year of teaching and saw on the television a little black and white television with my mom, we were watching the evening news, and I saw the riot that was happening at the University of Georgia, and we were horrified,” recalled Early. “I said, ‘That’s not right. They can’t do that. I’m going to transfer to the University of Georgia.’ And my mother looked at me, and she said, ‘Are you sure? We just saw a riot there. It’s too dangerous.’”

Early continued, “She told me for the first time about the murders of four Black people in Monroe, which was her hometown. She had never told me this before, and it was a horrific murder. And she said, ‘That’s why you shouldn’t go — because it’s dangerous.’ And I said, ‘Mom… I have to be on the active line. I have to do something about this. Because these Jim Crow laws are not going to go away, and I can help. I can go to school.’”

Accepted by the University, but not by its student body:

“I was not accepted,” Early said. “It really got under my skin because the students would sit far away from me in class and not even acknowledge my presence. But my first class, which was Advanced Music History, the first test that came up was to be held before the Fourth of July, but the rest of the students in the class — I wanted to go ahead and get it over with — but they wanted to wait, and so we waited until after the Fourth.”

“I studied and studied … When the professor returned the papers, he announced the fact that I had the highest grade in the class, which was an ‘A.’ And the students looked at me. I mean, you see, at that time, I think the prevailing thought was that Blacks could not compete academically with whites, and that’s why schools should not be desegregated … But it was probably because I studied during the holidays and they didn’t. But that changed. A lot of them, they would begin to talk with me in class — not outside of class — but that sort of broke down the wall of people just, all of them just ignoring me.”

Early makes a powerful gesture at the Atlanta Symphony:

“I took my fifth, sixth, and seventh graders to the Symphony, and at that time, the white students went in the morning, and the Black students, or Negro students, in the afternoon. When we went, I was aware because I had been sent a program that the students would be asked to stand at the beginning and sing a patriotic song. It didn’t say which song,” said Early. “When I heard that it was ‘Dixie,’ I told my students to sit down, and they didn’t know how to sing it because I had never taught it to them, and they did.”

“That was my, I guess, silent objection to the song because it was an offensive song then, and it is still today. I was teaching my students without being, I guess, obnoxious, that this was not something that they should appreciate.”

Mary Frances Early will deliver talks at two events on Monday, Jan. 17, open to attendees with reservations.

Her first event at the Atlanta History Center, in conversation with Hank Klibanoff, takes place at 2 p.m. More information is available here.

She will also host a Zoom event at 7 p.m., open to the public with registration. More information is available here.

Her new memoir, “The Quiet Trailblazer: My Journey as the First Black Graduate of the University of Georgia,” is available for purchase here.