Atlanta made a decision to do civil rights differently in the 1960s. Violence in the streets would not play out here. There were no dogs and no hoses. Politicians met with corporate leaders, civil rights advocates and the church to do things in a manner that did not end with atrocity as seen in other Southern cities.

It was a gentlemen’s conversation, rather than a brawl of ideals. This allowed the city to prosper financially and civically in a time when it didn’t seem realistic. That approach became known as the “Atlanta Way.”

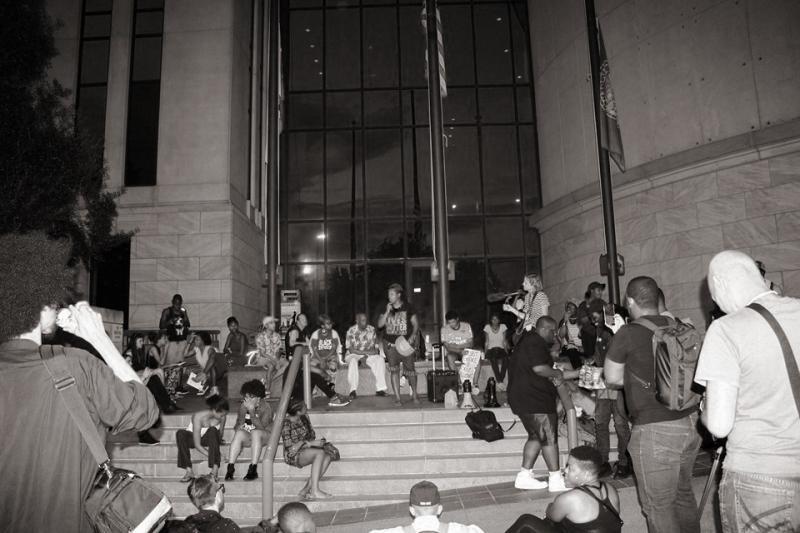

Enter #ATLisReady, a movement that started on the internet, but did not stay there. A group of organizers decided it was time for a movement that looked more like them.

#ATLisReady is representative of the underserved sects of black and marginalized people in Atlanta and ultimately across the nation, said organizer Avery Jackson, a Morehouse College senior. Their movement includes undocumented immigrants, transgender people and black Americans that don’t necessarily represent the elite.

On July 7 the movement began on Twitter, hence the hashtag, and was in direct response to the deaths of Alton Sterling in Louisiana and Philando Castile in Minnesota. July 8, people took to the streets, blocking a freeway ramp. July 12, they went to Buckhead, where the money is, they said.

They wanted reform, demands met. In their eyes, policing had to change.

Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed granted a meeting.

On July 18, the day of the scheduled meeting with Reed and Atlanta Police Chief George Turner, Jackson and his comrades thought they would get a chance to present their demands directly to those that could make change. They wanted police reformation, an end to racial profiling and critical funding for social services.

“ATL is Ready is a response to the people’s call,” said Jackson. “We knew as organizers and folks with experience in direct action and resistance and strategy around grassroots that we had a responsibility to keep this momentum going and to really push for progressive change for the people.”

Like Jackson, many organizers of #ATLisReady are college students. Others are community organizers and activists. The group wants to “amplify the Black and other marginalized voices in Atlanta.”

While the immediate response was to police violence nationally, #ATLisReady also wants to tackle issues of race, gentrification and economic justice specifically in Atlanta.

“We understand that each of our oppressions is linked to someone else’s,” said Jackson. “There is a real epiphany that folks have when they see that they can reimagine what their existence looks like in this country. That we don’t necessarily have to accept our conditions.”

A different kind of leadership

Leadership within the coalition is amorphous. They have no distinct face, no single leader that stands above the rest, and that’s how they like it. Jackson said that’s by design, because when one leader is present a tendency is for that leader to get flipped and start serving a more capitalist agenda.

The meeting with city leadership was not representative of what #ATLisReady organizers were looking for. It reeked too much of the old “Atlanta Way,” they said.

The group wanted the meeting opened to the public, but said the doors were closed with only a few leaders from various organizations allowed inside. So they rejected the meeting, opting instead to head back to the streets.

“The ‘Atlanta Way’ is this civil rights tradition of having one leader who’s suited and booted,” said Jackson. ”And his job — his because he’s a man — is to relay the message back to the people, but never allow the message to be relayed back up.”

Another issue #ATLisReady had with the meeting was that they thought there were leaders present who had not been at other meetings, marches, or protests. These other “leaders” didn’t represent #ATLisReady, but were more there for limelight, they said.

“Kasim Reed has been the mayor of Atlanta for seven years,” said Auriella Williams, a youth organizer, in a press release from #ATLisReady. “And Atlanta is still the mess it is today because he has always played exclusively to the needs and voices of the few, in private.”

A nation watching and waiting

The movement has made ripples in other cities. Jackson said they’ve had contact from activists in other spaces saying they are paying attention. Prominent activists like DeRay McKesson, who was arrested in Louisiana protesting the death of Alton Sterling, have taken notice.

“There’s a lot of folks who have been arrested in Baton Rouge actually who have been hitting us up and telling us that they’ve met folks in jail who are saying that they’re watching what’s going on in Atlanta and it’s keeping them engaged while they’re incarcerated,” Jackson said. “We have folks in L.A. who are connecting with us and telling us that they’re using the same strategy.

A respectful split

The split from older civil rights movements is not something that bothers the #ATLisReady movement. They understand, recognize, and respect the past fights of Atlanta civil rights, said Jackson, but they recognize that the old movement may not have included everyone for whom they’re fighting now, pointedly homosexuals and undocumented immigrants.

“The decision to reject the traditional Atlanta Way is reflective of a new ‘Atlanta Way’ being built,” said Jackson. “Because Atlanta has the opportunity to really lead the country in a progressive movement and we should not just sit on potential.”

Their tactics are different from the old way, too. Ambassador and Civil Rights leader Andrew Young called the group “unlovable brats.”

The group responded with black t-shirts with the quote on them.

“We think that it’s important for this movement to have personality and we’re going to make a joke from anything that’s not to be taken serious,” said Jackson. “We’re willing to piss off everybody for justice.We’re willing to piss off the grassroots community, and more importantly we’re willing to piss off people who look like us.”

Avery Braxton produced this story for the Next Generation Radio project.