Mar-a-Lago has dominated the headlines in recent weeks, courtesy of the now famous FBI search on former President Donald Trump’s Florida residence.

But long before it housed government documents, the opulent mansion had a rich and lively history. And it all begins with a wealthy heiress.

Mar-a-Lago’s early party years

Marjorie Merriweather Post was an heiress to the Postum Cereal Company – which eventually became “General Foods Corporation.” Post took over the company at just 27 years old after her father died, which made her one of the world’s richest women of the time.

She named this Palm Beach property fittingly. “Mar-a-Lago” means “Sea to Lake” in Spanish – and like the name suggests, it has the Atlantic Ocean on one side and Lake Worth on the other.

Mar-a-Lago was just one of her properties. Another notable home of Post’s was the Hillwood Estate in Washington, D.C., which is now a museum.

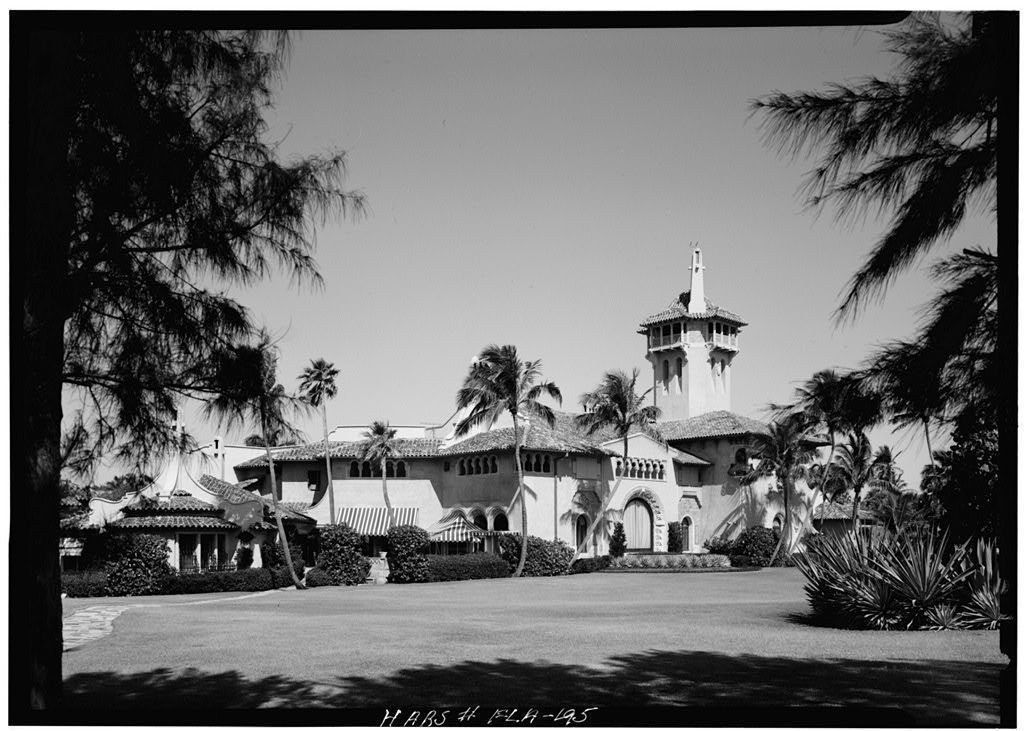

Construction on Mar-a-Lago took four years and cost Post about $7 million (which translates to more $100 million today.) Houses like Mar-a-Lago embodied the roaring ’20s — a time of booming wealth and consumerism.

Freelance journalist and PhD student Michael Luongo examined the Post Family Papers at University of Michigan and covered Mar-a-Lago’s history for Smithsonian Magazine.

“Even by Palm Beach standards, Mar-a-Lago was grandiose,” he wrote.

The property sits on about 20 acres, and the house is massive. It’s more than 37,000 square feet, complete with 58 bedrooms and 33 bathrooms. It’s decorated with 36,000 historical Spanish tiles, imported Italian stone, thousands of feet of marble, and gold-plated fixtures and gold leafing throughout the house.

Post was a hostess at her core – her New York Times obituary says she built Mar-a-Lago because her first Florida home “became too small for her parties.”

“Florida in the 1920s and the 1930s served the same role that it does now: it was a place where people vacationed,” Luongo told NPR. “But we are not talking about your ordinary middle-class family going to Disney. We are talking about the very elite who would come down to Palm Beach, who would come down to parties that she would host.”

Post hosted royals and diplomats, elaborate parties, and charity events, including the International Red Cross Ball. And plenty of this was open to the Palm Beach community surrounding Mar-a-Lago.

“She also was very keen on ensuring that the underprivileged were invited to events so that they could experience, for example, musical concerts,” Luongo said. “[Post was] a woman of means, very wealthy, very keen, very understanding of the importance of her role in society.”

According to Luongo, she hired the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey circus in 1929 to perform for underprivileged children for a charity fundraiser. It was important to her that these events made money for the charities she was supporting.

“She found ways to ensure that costs were reduced for a smaller organization,” Luongo said. “She made sure that if she opened up her doors, that it would serve a social purpose in the sense of society, but also serve a social purpose in uplifting society for those who were from poorer backgrounds or for charities.”

Mar-a-Lago was made a national historic site in 1969 by the Department of the Interior, and it was later placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

When Post died in 1973, she willed Mar-a-Lago to the federal government to be used as a retreat for Presidents and diplomats — she wanted it to be a “Winter White House.”

Ultimately, that didn’t end up happening because the government deemed it too costly to maintain. Houses like these are known as “white elephants” — a property that’s so big and expensive it becomes a burden.

“There were other examples of houses like this that don’t exist anymore. By the [1950s and 1960s], as tastes changed, as houses were sold by families, as people could no longer afford them,” Luongo said. “That’s why many over the years had been demolished.”

A bargain buy for a real estate mogul

When the Marjorie Merriweather Post Foundation put it up for sale, and after multiple purchases fell through, that’s when then real estate mogul Donald J. Trump entered the picture.

In December 1985, Trump purchased the property from the foundation for $5 million. He also paid millions more to purchase Mar-a-Lago’s antiques.

“He did get a beautiful property at a very, very low amount of money,” Luongo said.

“Without Donald Trump, would that house have been preserved or not? So that’s another thing to think about,” he said. “But, you know, it’s a beautiful piece of history and was always a piece of history.”

In 1995, Trump transformed his private residence into “The Mar-a-Lago Club” that we know today, where the initial fee to join is $200,000.

Fast-forward to 2017, former President Trump started referring to Mar-a-Lago as his own “Winter White House.” Post’s influence lived on through the glitzy interior of Mar-a-Lago that was featured as a backdrop for White House events and press conferences. During his Presidency, Trump hosted world leaders at the estate, including Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and China’s President Xi Jinping.

After his presidency, Trump moved to Mar-a-Lago full time. But most recently, Mar-a-Lago has been making headlines for the FBI investigation to seize government documents from the property.

In many ways, Mar-a-Lago is Post’s legacy, and now it is part of former President Trump’s too. It’s hard to know how Post would feel about Mar-a-Lago today.

“I can’t be in her mind, but I think in many ways she would be intrigued,” Luongo said. “I think that as somebody who used her position to promote the United States, to promote notions of equity, to promote notions of diplomacy… I think in that sense, she would probably be appalled.”

So in a way, Post got her wish: for Mar-a-Lago to live on as a “Winter White House.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))