Updated at 4:24 p.m.

Jeff Schoenberg wants to have “reasonable confidence” that the votes he casts when he goes to his polling place are accurately counted — and he doesn’t believe he gets that from Georgia’s election system.

He and other voters, along with an election integrity organization, have sued state election officials, alleging that the system is vulnerable to attack and has operational issues that amount to an unconstitutional burden on citizens’ fundamental right to vote and to have their votes counted accurately.

Election officials insist that they’ve taken appropriate protective measures and that the system is secure and reliable. They also say it’s up to the state, not the courts, to decide how Georgia’s elections are run.

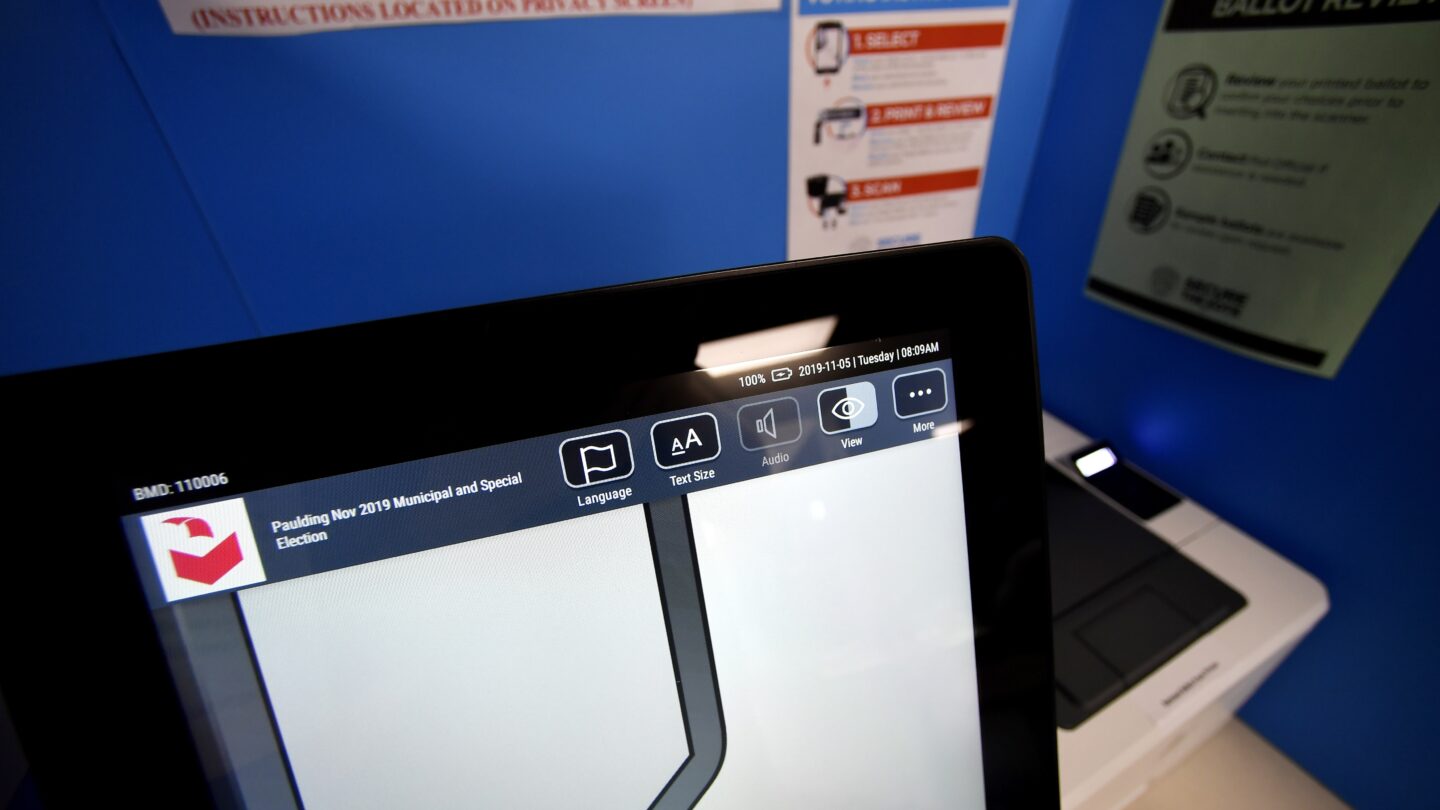

In a trial that began Tuesday, Schoenberg and the others are asking U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg to order the state to stop using the Dominion Voting Systems touchscreen machines used by nearly every in-person voter statewide. Instead, they argue, most voters should fill out hand-marked paper ballots, with a touchscreen machine at each polling place for people with disabilities. That would ensure voter intent is accurately captured and that meaningful audits can be done, they argue.

“My vote should be counted as cast. My particular point of view should be heard,” Schoenberg testified.

Georgia’s touchscreen voting machines print ballots with a human-readable summary of voters’ selections and a QR code that a scanner reads to count the votes.

Schoenberg said there’s no way he can verify that the ballot accurately reflects his selections: “I can’t read a QR code.”

During his opening statement, David Cross, a lawyer for Schoenberg and a handful of other voters, said that despite reliable evidence showing that the state’s voting machines are vulnerable to attack, state officials have shown little concern and have failed to take appropriate action.

University of Michigan computer science expert J. Alex Halderman, an expert witness for the plaintiffs, examined a Georgia voting machine and wrote a lengthy report identifying vulnerabilities he said he found and detailing how they could be used to change election results. The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or CISA, in June 2022 released an advisory based on Halderman’s findings that urged jurisdictions that use the machines to quickly mitigate the vulnerabilities.

Cross played a video clip of Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger saying Halderman was “way off base,” that anyone with the kind of access Halderman had could “do something,” but that’s “not the real world.”

Cross then showed surveillance video clips of unauthorized people walking into the elections office in rural Coffee County on multiple days in January 2021 and being allowed by local election officials to access voting equipment. Those breaches, uncovered and exposed by the plaintiffs, resulted in the state’s election software being put online and downloaded by an unknown number of people.

“What we will show in this trial is the only person who doesn’t live in the real world when it comes to election security is the secretary of state,” Cross said.

Showing a graphic of an empty chair, Cross noted repeatedly throughout his opening that Raffensperger does not plan to testify during the trial to answer questions or explain his decision making. Totenberg had ordered the secretary of state to appear, but the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last week that he doesn’t have to.

Robert McGuire, an attorney for several voters and the Coalition for Good Governance, which advocates for election integrity, said he recognizes that the judge’s decision is a difficult one. But he said the current system is “profoundly insecure, unreliable and untrustworthy” and that if those concerns aren’t addressed, “a disaster is waiting to happen in 2024.”

Bryan Tyson, a lawyer for the election officials, said the proper functioning of the election system is “critically important,” and it’s up to the state to choose what system it wants to use.

Halderman did not find any evidence of malware installed on any of the equipment he looked at, and the plaintiffs have provided no evidence that any election equipment has been hacked or votes altered, Tyson noted.

While citizens have the right to vote, they don’t necessarily have the right to vote in their preferred manner, he said. In deciding this case, the judge must look at whether the system is constitutional, even if it’s not what she would deem ideal, he said.

Any burden faced by the plaintiffs is outweighed by the state’s interests, including clearly recording voter intent, having a paper trail, allowing people with disabilities to vote without being relegated to a separate category and making it easy for election workers to give voters the appropriate ballot, Tyson said.

Every election system has vulnerabilities, but that does not make them inherently unconstitutional, Tyson argued. He said the idea that elections are not perfect has been used by people across the political spectrum to sow distrust in elections.

“Georgia elections work,” he said. “Georgia election officials do their work well, regardless of attacks from the right or the left.”

After the 2020 election, supporters of former President Donald Trump spread wild conspiracy theories about Dominion voting machines, arguing the equipment had been used to steal the election from him. The company has responded aggressively with lawsuits, notably reaching a $787 million settlement with Fox News in April.

Dominion, which is not a party to this case, said in a statement that there are “many layers of robust operational and procedural safeguards in place, overseen by local election officials, that help protect our elections and serve to ensure that any physical tampering is prohibited.”

Totenberg, who has previously expressed concerns about the state’s election system and its implementation, wrote in an order in October that she cannot order the state to switch to a system that uses hand-marked paper ballots. But she wrote that she could order “pragmatic, sound remedial policy measures,” including eliminating the QR codes on ballots, stronger cybersecurity measures and more robust audits.